On Wednesday, October 11, 2023, an unusual truck circled the streets surrounding Harvard Yard, pausing outside the bakery across from Widener Library. Three video screens on its sides showed the faces and names of Harvard students. Accompanying text, in newspaper typeface, labeled them “Harvard’s Leading Antisemites.”

By now, nearly everyone is familiar with how it happened. The day after the October 7, 2023, Hamas terrorist attacks on Israel, Harvard’s Palestine Solidarity Committee circulated a letter holding “the Israeli regime entirely responsible for all unfolding violence.” Representatives of 33 student organizations, from overtly political groups to a South Asian dance troupe, cosigned it. And amid the angry backlash, some prominent voices called out for a particular form of retribution. Investor Bill Ackman ’88, M.B.A. ’92, posted on X that Harvard should release the names of students who belonged to the signing groups “to insure [sic] none of us inadvertently hire any of their members.” If students support the letter, he continued, their views should be “publicly known.”

A thousand miles away, in a seaside suburb of Jacksonville, Florida, Adam Guillette came upon the student letter. Since 2019, Guillette has run Accuracy in Media, a right-wing nonprofit group. Before October 7, his primary project had been investigating diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts at universities to ascertain, he says, whether administrators “are putting politics ahead of…education.” But he also dabbled in protesting antisemitism; in the fall of 2022, he brought a digital billboard truck to display student names at the University of California, Berkeley School of Law after nine student groups there said they would not invite speakers who had expressed support for Zionism.

Guillette viewed the Harvard letter as tantamount to antisemitism and support for Hamas, calling it “a horrible action.” Part of his outrage was personal—Guillette is Jewish and says his grandparents fled antisemitism in the Soviet Union. And part of it was professional—exposing students for speech he perceived as antisemitic helped him advance his crusade against what he considered to be excesses in higher education.

He sprang into action, combing through the Crimson’s archives and the signing organizations’ social media pages to compile a list of group leaders. He bought ads that showed up on the feeds of pro-Palestinian students’ LinkedIn and Facebook contacts to target their personal and professional networks. Then, he flew to Cambridge and rented the truck. The roving digital billboard circled campus for about a month, visited the Vermont hometown of one named student, and came to be known as the “doxxing truck.”

Doxxing, a term that grew out of 1990s hacker culture, refers to “dropping documents”: releasing an individual’s personal information without permission. This was one of the first activities that brought the digital world into the physical, says Bemis professor of international law Jonathan Zittrain: a doxxing effort “could produce thousands or millions of touchpoints from strangers, including harassing calls, threats to employment, or intimations of violence, against a targeted person.” Outside the gates of Harvard Yard, students featured on trucks (sent by Guillette as well as other organizations) were called terrorists, baby killers, Hamas apologists, and antisemites. Some people were moved by Guillette’s doxxing efforts to threaten the student signers with violence, including death and rape; some also made racist remarks.

Is doxxing a form of justice or an assault on free speech? At Harvard, both interpretations collided in real time during the past two years, exposing deep divisions over the meaning of community, responsibility, and free expression—and changing campus life in ways that still reverberate today.

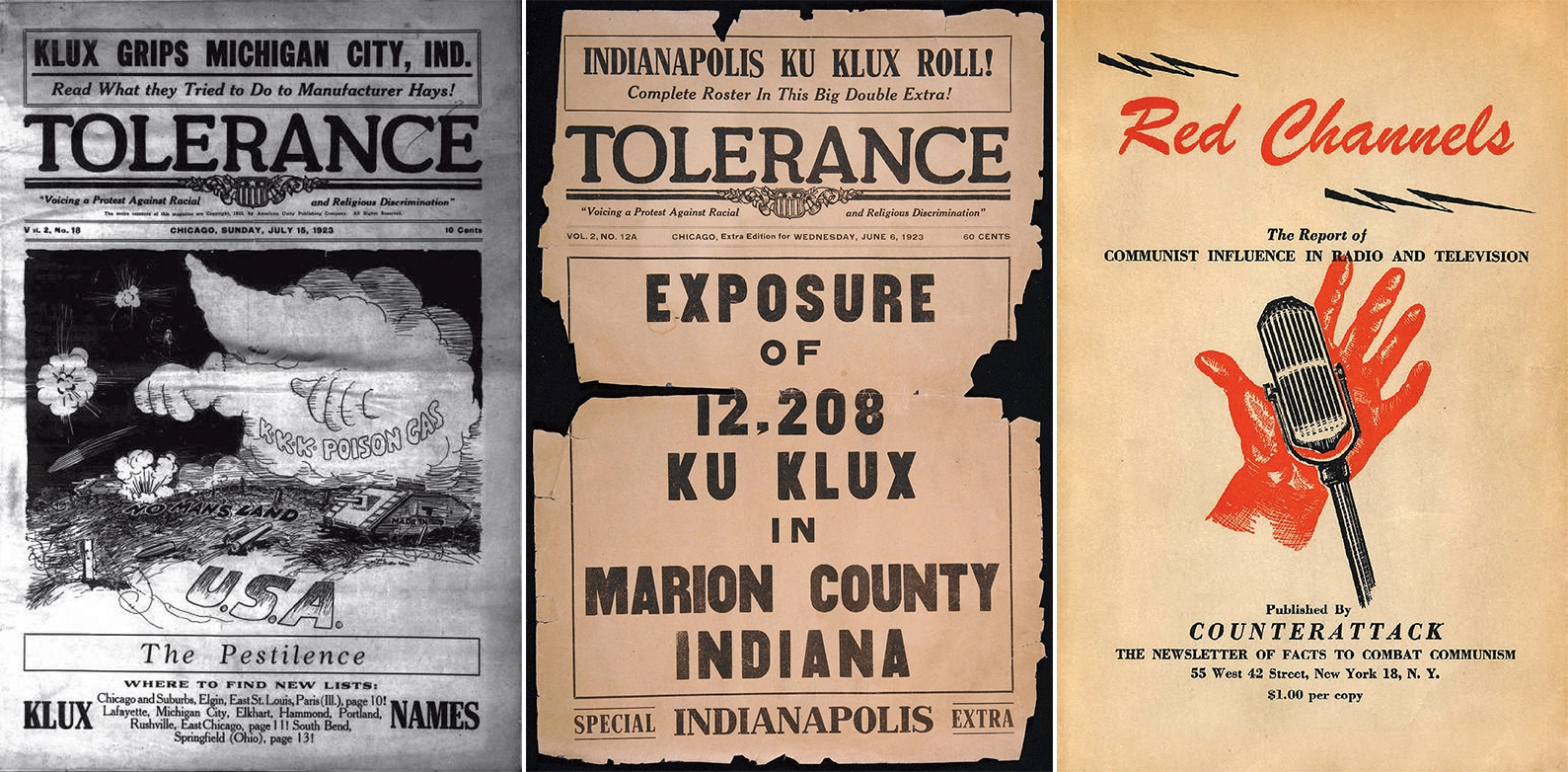

Guillette denies that his actions constituted doxxing, arguing that the information he shared was already public. Still, his tactics echo a longer American tradition—one rooted in a vigilante spirit and frustration that institutions, whether courts or universities, fail to take perceived threats seriously. Though today’s technologies make it far easier to identify faces, names, and employers, the practice itself predates the digital age and has targeted figures on both the right and the left: neo-Nazis in Charlottesville, abortion rights advocates after the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization Supreme Court decision, communists during the Second Red Scare, and Ku Klux Klan members in the 1920s. What links these campaigns is not just their swiftness, but their bluntness. They often presume guilt rather than innocence, seek retribution for speech and affiliation alike, and spiral beyond their initial intent—silencing some, galvanizing others, and eroding trust in the communities they claim to defend. The tools may have changed, but the impulse to name, shame, and punish in public remains deeply American.

In the late 1940s, a trio of former FBI agents believed the government was acting too slowly against what they considered to be a massive threat: communism. During World War II, the agents had worked together on the FBI’s New York-based communist squad, tracking infiltration efforts. In 1947—three years before U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy’s famed anticommunist crusade—they began publishing Counterattack, a weekly four-page newsletter focused on combating communism in the United States. They publicized names because they feared an imminent communist revolution and wanted people to know who might lead that charge.

[These campaigns] often presume guilt rather than innocence...and spiral beyond their initial intent.

The 1950 publication of their booklet Red Channels: The Report of Communist Influence in Radio and Television launched their project into the mainstream. The impact of that list of 151 alleged communists, from harmonica players to A-list stars, was visible and dramatic: an NBC pilot was pulled off the air hours before its debut because advertisers did not want to be affiliated with the Red Channels-listed star. The report helped spark the Second Red Scare, during which 10,000 Americans were fired for alleged communist affiliations or activities over the course of 15 years.

Decades earlier, in 1922, a Chicago lawyer named Patrick O’Donnell used the tactics of doxxing to attack the far right. Concerned about the growing political power of the local Ku Klux Klan, he noted that the Klan routinely distributed lists of Klansmen-owned businesses to its members to encourage them to shop there. (If a shop owner’s affiliation stayed secret, he could simultaneously profit off of Klansmen and the groups they antagonized.) O’Donnell saw the Klan’s desire for anonymity as an exploitable weakness. He began publishing a weekly newspaper, Tolerance, which listed the names, addresses, and occupations of Klansmen, including salesmen, grocers, and executives, targeting businesses small and large. Tolerance attacked social ties, too, asking “Is Your Neighbor a Kluxer?” before releasing local names.

Doxxing harmed both individual Klansmen and the Klan; the group’s appeal dimmed once the economic benefit of membership turned into a burden. But the naming strategy also sparked some prominent mistakes, leading to legal challenges for the doxxers. At one point, Tolerance accused gum magnate William Wrigley Jr. of being in the Klan, but the signature on his Klan membership form turned out to be forged, lifted from a gum wrapper logo. The ensuing libel suit inspired dozens of accused Klansmen to file, too.

Faced with financial ruin, Tolerance stopped publishing in 1925. The Counterattack team, too, fended off seven libel suits—six of them based on information published in Red Channels. They won them all, but the financial toll led the publishing company to stop doxxing.

Today, the internet makes doxxing easier than ever, both in spreading information and seeking it out. Groups like Canary Mission—a doxxing website focused on exposing anti-Israel activism—have publicized the names of students and faculty who have publicly articulated anti-Israel views, coauthored columns supporting the Boycott, Divest, and Sanction movement, been members of groups that cosigned anti-Israel letters, or participated in protests. Before the advent of the internet—especially social media—much of that activity would have remained within the campus gates. Contact information used to be harder to come by, too: whereas, once students could only be reached via their parents’ landlines or physical mail, they now have social media pages and easily guessable emails. All speech is public, and everyone is reachable.

Advocates of the name-and-shame efforts after October 7 have said they are performing a service at a time of rising antisemitism. A quarter of Harvard’s Jewish students said they felt physically unsafe on campus and nearly half felt mentally unsafe during the 2023-2024 academic year, according to a report from the school’s antisemitism and anti-Israel bias task force. The report, released in April 2025, found that many Jewish students—particularly Israelis—felt the “unfettered expression of pro-Palestinian solidarity and rage at Israel” was “directed against them as well.” Doxxers say they are defending a vulnerable group that faced continued harassment: brazenly antisemitic statements circulated on the anonymous Sidechat app after October 7, and Jewish students reported intimidation from professors and students involved in protests and encampments. Guillette says that the nation “needs” to know the identities of Harvard students “who are openly racist and openly defend violence.”

But others argue that doxxing’s true intent is to squelch free expression. Professor of history Kirsten Weld, who leads Harvard’s chapter of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP), says that a primary goal of groups like Canary Mission “is to defame and terrorize members of our campus community in order to chill their speech.”

Experts note that doxxing is designed to provoke a reaction. “Information is deeply contextual,” says Jessica Fjeld, an affiliate of Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society. Doxxing campaigns, she says, “are releasing that information directly to communities that they think will be inspired to act.”

And there can be broad consequences for ending up on a list. Canary Mission bills itself as employment-focused; its website says, “It is your duty to ensure that today’s radicals are not tomorrow’s employees.” But during the AAUP v. Rubio trial this summer, in which a group of professors sued the government for attempting to deport international students who had engaged in pro-Palestinian speech and activism, a senior Department of Homeland Security official testified that the government used Canary Mission’s list of names to figure out whom to investigate and potentially deport.

Guillette says that the nation “needs” to know the identities of Harvard students “who are openly racist and openly defend violence.”

Many of the Harvard students whose names were exposed after October 7 knew their activism might invite unwelcome exposure. The student group Harvard Divinity School Jews for Liberation was profiled in a 2022 Crimson article that discussed the group’s “work to decouple Judaism and Zionism”; before publication, members had talked about potential backlash.

Clyve Lawrence ’27, the cofounder of the student group African and African American Resistance Organization, says that when his club endorsed the October 8 letter, he knew that as a public leader, he might face criticism. Lawrence says he was “willing to defend” the letter and his beliefs.

Even students who understood the risks were sometimes surprised by the truck and the doxxing efforts. One Jewish Divinity School student, who asked to remain anonymous due to concerns about online harassment, recalls struggling to catch their breath—then bursting into tears—when friends texted them that Canary Mission had launched a page for them.

The influx of outside messages drained students’ time and energy. One doxxed Harvard Kennedy School student who graduated before the October 7 attacks says that they had to “figure out how to remove random websites on the internet, whereas [they] could have been more focused on…activism related to Gaza.” In late October 2023, Harvard provided doxxed students access to DeleteMe, a service that removes information from websites that sell personal contacts, but Fjeld says that DeleteMe is much more effective when used before doxxing occurs. “Once the information is out there,” Fjeld says, “there’s actually not a lot you can do.”

Several doxxed students expressed frustration with Harvard’s response. Some felt that then-President Claudine Gay should have condemned the trucks more quickly and forcefully. Others felt that the office set up to assist doxxed students was not particularly helpful.

And even some people who have raised concerns about campus antisemitism have suggested that the doxxing went too far. Former president Lawrence H. Summers, who criticized the October 8 letter and maligned the University for not strongly, publicly, and quickly condemning the terrorist attacks, posted on X on October 11, 2023, asking that “everybody take a deep breath…This is not a time where it is constructive to vilify individuals and I am sorry that is happening.” (Bill Ackman, who called for the naming of student activists, declined to comment, referring Harvard Magazine to his past statements instead.)

Guillette, like doxxers of the past, has made mistakes. When he initially created websites for students he had named, each website said the student had “signed this hateful, antisemitic letter.” But several of those students had graduated before October 7 and were no longer involved in their clubs. Now, a typical website for a named student says the individual “was a leader of an organization that signed.” Guillette says he removed the names and websites of students who reached out individually to apologize and rescind their signatures.

He also says that, in the weeks after he launched his truck, he was doxxed himself. His address was leaked and, 13 times, he was “swatted”: police arrived at his house after people who disliked his actions falsely reported crimes at his home address. He and his wife spent more than a month living in hotels and had to lock their credit, since doxxers had publicized his Social Security number and people were applying for credit cards in his name.

But while Guillette was getting swatted, he was simultaneously bringing video trucks to students’ addresses and to Elmwood—used as a residence by Harvard’s president—where Claudine Gay lived. (Guillette did not view the trucks at Elmwood as a violation of privacy because it was “University property,” he says, “not a private residence.” And he says he draws “an important distinction” between himself and those he considers to be doxxers, since Accuracy in Media does not publicize addresses or show the fronts of people’s homes.) The swattings did not dissuade Guillette from pursuing his work, he says: “We taught these radicals a lesson that there will be accountability for their racist actions, and we won.”

After their names were shared, students were hounded through their social media pages, direct messages, email, and print mail. Some lost jobs, including one with the law firm Davis Polk, which announced the withdrawal of a student’s offer 10 days after the Hamas terrorist attacks. Others changed their job searches. The Kennedy School alum, an international student who no longer lived in the U.S. by October 7, was advised not to return to the U.S. because being detained could jeopardize future visa applications; instead, the former student is working abroad and relying on friends to slowly retrieve items they left behind in the U.S.

Some students had less difficulty. The Jewish Divinity School student sought postgraduate employment in the Jewish nonprofit space and often discussed the doxxing in job interviews. Many organizations offered jobs anyway, and the former student now works for a Jewish social justice group.

But doxxing had a discernible effect on Harvard’s campus. Students viewed each other with increased skepticism. Phones became weapons. Protesters frequently donned blue surgical masks—unprotected faces could be posted online, and students were sometimes doxxed for mere attendance at protests. Around the edges of demonstrations, student marshals in neon vests patrolled, ensuring that onlookers did not photograph faces.

And one early confrontation became physical. When an Israeli first-year business student filmed students as he walked through an October 18, 2023, protest, demonstrators surrounded him with raised keffiyehs and vests, and two graduate students allegedly physically assaulted him.

The pair were charged with assault and battery, but in April 2025, a Massachusetts judge ruled that they will not face trial and instead will take an anger management course and do community service. In a lawsuit filed against Harvard in July, the Israeli student said that his alleged attackers were also rewarded with a Harvard Law Review scholarship and a class marshal role at graduation—and that Harvard did much more to protect the doxxed students than it did to shield Jewish students from harassment.

After October 7, the classroom “banter was gone...Everyone was stressed and on their toes. People were picking sides.”

Doxxing chilled the classroom, too, students have said. One student quoted in the University’s anti-Muslim, anti-Arab, and anti-Palestinian bias report said that after October 7, the classroom “banter was gone…Everyone was stressed and on their toes. People were picking sides.”

Students also noted that some of the information Canary Mission published on its website contained material that only Harvard students could access, which means students were exposing one another. Peer trust eroded. Of the 21 students and alumni still listed by Accuracy in Media, only four were willing to speak with Harvard Magazine, even anonymously.

Activists like Guillette consider that a victory: a way to push views they see as harmful to the margins of acceptable speech. But in some cases, the doxxing at Harvard encouraged pro-Palestinian protesters to keep going. After Clyve Lawrence got doxxed, he concluded that “short of physical, actual harm…this is basically the worst it will ever get in my organizing.” The attention was stressful and uncomfortable, he says, but he made it through.

Lawrence still wants to protest—maybe more now than ever. He is confident that his beliefs, which some presently consider fringe, will become the accepted norm within a few years. He says that his page on the Canary Mission website, intended to shame him for his pro-Palestinian stances, will one day become a badge of honor, “a document of the actual level of harassment that I and others were facing.”

“The irony of harassment online,” Lawrence says, “is that when you do it, it has the chance of actually emboldening your opponents…I feel more empowered than ever to support Palestine.”