Standing on the Greenland ice sheet—flat, white, and stretching for thousands of miles—it would be hard to imagine that, buried in the centuries of compressed snow, there lies a record of the Roman Empire’s mining activities.

For much of recorded history, the story of human environmental impact seemed to begin with the Industrial Revolution. Yet, in recent decades, research into glacial ice has shown that ancient societies, including the Romans, altered the atmosphere long before factory chimneys darkened modern skies. Joseph McConnell, research professor and director of the Trace Chemistry Laboratory at Nevada’s Desert Research Institute (DRI), visited Harvard on November 19 to discuss his work with students in a first-year seminar in the History of Art and Architecture (HAA) titled “Looking for Clues: Ancient and Medieval Art at Harvard.” The course is taught by Eurydice Georganteli, lecturer in art history and numismatics and senior research fellow at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science (MPIWG) in Berlin. McConnell’s seminar and his contribution to the international symposium Making and Unmaking Value I: Transformation through Time that also took place at Harvard (November 20-21), were part of the HAA-MPIWG collaborative project “Metals, Minerals, and the Life Cycle,” which Georganteli co-directs with Professor Dagmar Schaefer at MPIWG.

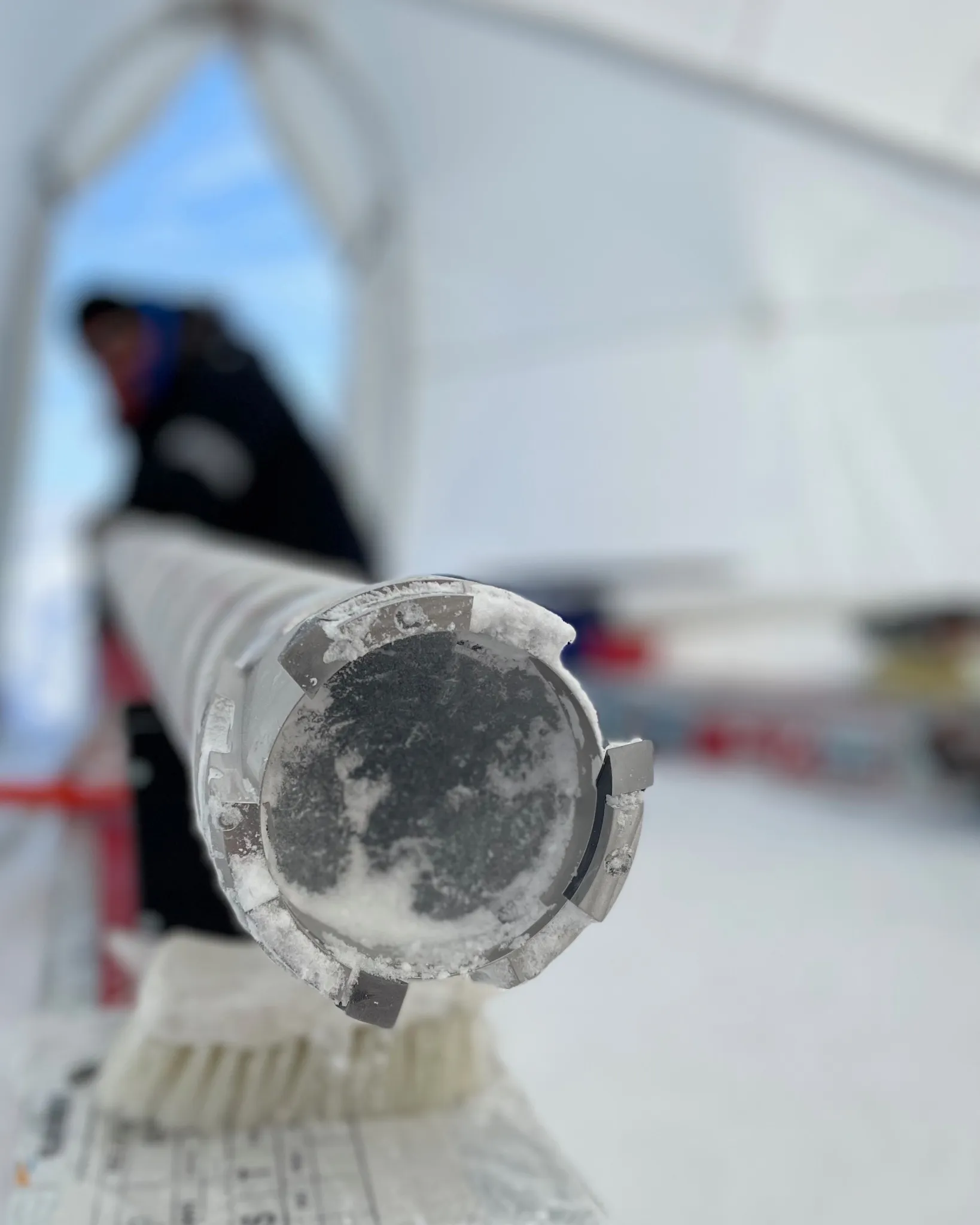

Seated around a table, students watched cinematic slide after slide of McConnell and his colleagues traversing glaciers in Greenland, Antarctica, and the Americas, all in search of optimal drilling sites. McConnell spends a lot of his time drilling in very, very cold places.

In ice core research, scientists collect samples from deep within glacial ice sheets, which they later analyze and compare. As McConnell explained to the Harvard class, each snowfall traps microscopic particles: dust, ash, pollen, trace elements, and sea salts. These become sealed into the layered ice (almost like tree rings) and entombed for millennia. Greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane are also preserved as tiny bubbles. By studying the glacial subsections, scientists can directly measure the composition of ancient atmospheres, including pollutant levels.

Among the clearest contaminants McConnell has found trapped in glacial ice is lead—a largely “anthropogenic,” or human-made pollutant, occurring at naturally low background levels. Much of ancient civilizations’ silver (heavily prized by the Romans and Phoenicians) came from lead-rich ore, and smelting released measurable lead into the atmosphere.

As McConnell explained, atmospheric lead rises during periods of intensive mining and metallurgy, such as Roman and Phoenician prosperity, and drops sharply during periods of political instability, including war, demographic collapse, and pandemics. These economic upturns and downturns are reflected in the glaciers of Greenland, where McConnell and his team drilled for data.

Major events in ancient history, including the Crisis of the Roman Republic (an extended period of economic, political, and social instability from about c. 133 BCE to 44 BCE), the Third Century Crisis (an era of military upheaval from 235-284 CE, after which the Roman Republic split into three separate political entities), and the decline of Phoenician mining networks, are all captured in the Greenland ice cores. Plagues also leave distinct signatures in the ice. The Black Death (which lasted in Europe from approximately 1346-1353 CE) for instance, coincides with a dramatic drop in medieval lead emissions. (Read more in “Harvard Historians: Ice Records Shed Light on Medieval Climate” by Marina N. Bolotnikova).

Glaciers also tell something about the human impact of ancient lead pollution. McConnell’s team used atmospheric and aerosol modeling to “invert” their ice-core data—working backward from the minute traces of lead preserved in the ice to estimate the volume of emissions that must have been released into the air to produce those layers.

They then used “forward” modeling to estimate what air-quality conditions around Europe would have looked like at the time. (Forward models are computer simulations that take those reconstructed emissions and show how lead particles would have traveled through the atmosphere—and thus, how much pollution people on the ground would have breathed).

After reconstructing the pollution levels, McConnell’s team brought in public-health experts. Using epidemiology, they estimated the blood-lead levels of people at the time based on lead in the atmosphere. “And then finally,” McConnell continued, “we used modern epidemiology to estimate declines in cognitive function [based on these blood-lead levels].” Using current science linking blood-lead levels to IQ loss, the scientists estimated how much cognitive harm ancient populations would have suffered from airborne lead pollution.

Airborne lead pollution alone may have lowered cognitive function in Roman children by 2–3 IQ points. (This figure excludes other exposure pathways such as leaded wine, pottery, cosmetics, or plumbing). Basically, civilizations were accidentally poisoning themselves with the things they produced for thousands of years, just as modern civilizations did (notoriously) in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

McConnell also contrasted these findings on Roman IQ points with the more recent past. He showed students the data from his own childhood in the 60s and 70s (a peak era for lead pollution, especially in the Northern Hemisphere, because of widespread use of leaded gasoline and minimal environmental regulation).

According to the same process of inference, he said that Baby Boomers may have suffered an average lead-induced decline of 9.2 IQ points. (The classroom gasped simultaneously). “We have great expectations of you guys because your IQs were much, much less damaged by lead exposure than my generation,” McConnell joked.

The first major lead-pollution regulation, the U.S. Clean Air Act—enacted in 1963 and amended by subsequent administrations—led to an 80 percent decline in Arctic lead pollution levels within a decade. This is also reflected within the glacial ice cores that McConnell and his team extracted, which showed an equivalent reduction in pollution within the ice. As McConnell emphasized, rapid changes like this suggest the effectiveness of policy interventions.

McConnell emphasized that today’s pollution will similarly accumulate in Earth’s icy polar archives. These days, he is studying the record of microplastics and “forever plastics” (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS) that are gradually becoming embedded in the ice.

McConnell ended the class on a sobering note. While people tend to think of lead pollution as a bygone issue, it’s not. He cited a recent New York Times investigation, which found that crude lead-recycling factories in Ogijo, Nigeria, (which supply U.S. car and battery companies) are blanketing nearby homes, schools, and farms in toxic lead dust, leaving a majority of residents with dangerous blood-lead levels.

The cryosphere, he said, is “an objective recorder of history.” The layers of ancient lead preserved in ice show how easily human activity can reshape the atmosphere and impact health. But if the rapid decline in Arctic lead after U.S. regulations in the 60s and 70s demonstrates anything, it is that policy is revealed in the ice. When societies and governments choose to act, the atmosphere responds.