Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

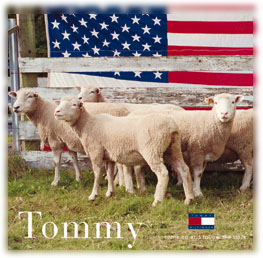

A "parody ad" from the Vancouver organization Adbusters satirizes the herd instinct among fashion consumers. COURTESY ADBUSTERS

A "parody ad" from the Vancouver organization Adbusters satirizes the herd instinct among fashion consumers. COURTESY ADBUSTERS |

MAMMON AGONISTES

Since World War II, real income in the United States has more than tripled--but without increasing our sense of personal well-being, according to surveys. In fact, aside from the poor (whose outlook improves markedly if they escape poverty), happiness and income are generally unrelated. Yet in the last two decades, Americans have indulged in an orgy of consumer spending. The average American's spending rose at least 30 percent, and perhaps as much as 70 percent, between 1979 and 1995. According to senior lecturer on women's studies Juliet Schor, "The story of the eighties and nineties is that millions of Americans ended the period having more, but feeling poorer."

In her new book, The Overspent American, Schor explains this paradox in terms of the "new consumerism," a shift in how Americans view "competitive spending"--the kind of buying we do to establish our social status. Competitive spending embodies the classic dynamic of "keeping up with the Joneses." Most Americans tend to attribute such motives to others, not to themselves, Schor observes: "We live with high levels of psychological denial about the connection between our buying habits and the social statements they make."

Moreover, the nature of competitive spending has changed. In the 1950s, the Joneses were neighbors--by definition, people who lived in comparable housing and were also near neighbors in income. Americans then typically aspired to lifestyles pegged about 20 percent above their prevailing standard of living. But starting around 1980, says Schor, "A shift took place in that comparative process. Everyone--no matter where they were in the economic spectrum, but especially the entire middle class--began comparing themselves to the top 20 percent of the income distribution. This new consumerism drastically widens the 'aspiration gap' between who you are and who you aspire to be."

What drove this change? One factor is the increasing lopsidedness of the income distribution. Since the 1970s, the bottom 80 percent of the population has become relatively worse off, while the top 20 percent has prospered disproportionately, Schor explains. Between 1979 and 1989, for example, the top 1 percent of households fattened their real annual incomes from a mean of about $280,000 to $525,000--and boosted their share of the nation's financial assets (stocks and bonds, for example, as opposed to real property) to just under one-half.

At the same time, electronic media have come to shape our image of the Jones family. "Television has become much more important in giving people information about other people's lifestyles," says Schor. Instead of comparing ourselves with our neighbors, "We're keeping up with our television friends. And for the most part, television shows portray upscale lifestyles--way above the American norm," she adds. "A TV family that's supposed to be middle-class will be living in a million-dollar home. On Friends, young people who are unemployed or working as waitresses live in apartments that, in the real world, would rent for thousands of dollars a month."

Watching more television, surveys suggest, inflates perceptions of how much the average American has in material terms. Now Schor presents new data indicating that "the more television someone watches, the less money they save, and the more they spend."

Surveys have also documented the skyrocketing aspirations of Americans. A 1986 Roper poll asked, "How much money would you need to make all your dreams come true?" and found a mean reply of $50,000. By 1994, that "dream-fulfilling" level had doubled to $102,000--and those earning $50,000 or more felt they would need $200,000. As a result, Americans have taken on record levels of debt, Shore says: "People have to spend higher fractions of their income--or above their income--to reach their aspirational targets."

Debt service as a percentage of disposable income now stands at 18 percent, even higher than in the recession of the early 1990s. Furthermore, the average American household now saves only about 3.5 percent of its disposable income, half the level of the early 1980s, before spending pressures cranked up.

In response, Schor finds, more Americans seem eager to wean themselves from the earn-and-spend treadmill. She includes a chapter on the counter-trend toward "downshifting"--choosing priorities like gaining greater control over one's time by working and spending less (see "Upward Trend: Downshifting," Harvard Magazine, September-October 1995, page 12). Schor herself empathizes with the revolt against the relentless cycle of material consumption. "It's an irrational system," she concludes. "If everybody upscales together, and what matters is keeping your relative position, then you run faster and faster just to stay in the same place."

~ Craig Lambert