Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

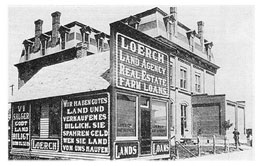

Signs of a multilingual heritage. In this nineteenth-century photograph, Loerch Realty, of Steele, North Dakota, does business in English, German, and Norwegian. NORTH DAKOTA INSTITUTE FOR REGIONAL STUDIES

Signs of a multilingual heritage. In this nineteenth-century photograph, Loerch Realty, of Steele, North Dakota, does business in English, German, and Norwegian. NORTH DAKOTA INSTITUTE FOR REGIONAL STUDIES |

Make way for A Saloonkeeper's Daughter. Her tale is as much a work of American literature as Carrie's own. Its heroine, Astrid Holm, is a sensitive girl growing up in Norway with a cold, bourgeois, businessman father and a mother who, shamefully, has been an actress. Father forbids mother to act again or to tell of her past. But, full of unhappiness, she does tell Astrid, and then she dies. The father's fortunes sink. He emigrates to Minneapolis, and sends letters home implying that he prospers. Astrid joins him to find herself in squalor, plagued by loutish immigrants who make unwanted sexual advances toward her in her father's saloon. Now her father wants her to act--in the saloon because it will sell more beer. A rich man courts her, but she doesn't love him. She breaks that off, becomes a Unitarian minister, and lives with a woman doctor. The novel is suffused with gloom and undertones of Norse mythology. It was written by Drude Krog Janson, an educated Norwegian woman living in Minneapolis, and was first published in 1887 in that city and in Copenhagen. Now it is forgotten in Norway, as literature by emigrants tends to be in homelands everywhere. The book was never widely known in the United States because it was written not in English but Norwegian.

But it's a good novel, says Werner Sollors, Cabot professor of English literature and professor of Afro-American studies. He and Marc Shell, professor of English and of comparative literature, founded the Longfellow Institute at Harvard in 1994 and have set out to find and bring back for study a multitude of lost texts--culturally, historically, or aesthetically valuable--that were written in what is now the United States in languages other than English--Omar ibn Said's 1831 narrative in Arabic of his enslavement and life in North Carolina, for instance. Johns Hopkins University Press will publish up to four of these works a year, with pages of English translation facing pages of Portuguese, Spanish, French, Dutch, Russian, Yiddish, Chinese, Japanese, or various Amerindian languages. Another early item in the series will be Ludwig von Reizenstein's novel The Mysteries of New Orleans, in its first English translation. Published originally in 1854-55 in one of New Orleans's German-language newspapers, it bursts with horror, eroticism, revenge, rage, and explicit lesbian love, and it scandalized the town. "It is often said that American literature has few novels of manners," says Sollors. "But it has quite a few. They just weren't written in English." The Longfellow Anthology of American Literature: A Multilingual Reader with English Translations, offering texts in different genres written in 27 languages, will launch the series in 1999, a fresh charge for the canon of American literature.

Some of these writings we simply didn't know about, and they will change our understanding of life in America, says Sollors. They will continue the work of multiculturalism by encouraging scholars to pay heed not only to race, class, and gender issues but to language. The institute promotes what Shell calls "the civil rights of language"--to give silenced parts of the American conversation a second hearing. "Sometimes," he says, "we find books that no one has looked at for a hundred years, and some of them are astonishing works of literature." Like A Saloonkeeper's Daughter, due in 1999. In the dust they may have been, but resurrection is at hand.

~ Christopher Reed