Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

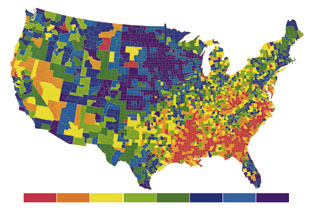

Key, from left to right: 70.0-77.1; 77.1-78.1; 78.1-78.6; 78.6-79.1; 79.1-79.5; 79.5-80.1; 80.1-80.8; 80.8-90.0. COURTESY CENTER FOR POPULATION STUDIES

Key, from left to right: 70.0-77.1; 77.1-78.1; 78.1-78.6; 78.6-79.1; 79.1-79.5; 79.5-80.1; 80.1-80.8; 80.8-90.0. COURTESY CENTER FOR POPULATION STUDIES |

THREESCORE--OR TWOSCORE--AND TEN

This staggering 41-year range within U.S. borders surpasses even the wide disparity of life spans among other nations, according to Christopher Murray '83, M.D. '91, associate professor of international health economics at the School of Public Health. Murray's findings on U.S. survival rates, measured by county, bring together census information and data from the National Center for Health Statistics and the Centers for Disease Control. (To achieve statistical reliability--which requires populations of at least 20,000--he collapsed the least populous of the 3,000 U.S. counties into clusters, resulting in 2,077 "county units.")

Murray, who patterned his current research after his earlier analysis of global disease trends for the World Health Organization, was surprised that "the black rural poor--particularly in the Mississippi Delta region--have a mortality pattern and a cause of death pattern that's more like a developing country than anywhere else. Life expectancies are worse than India [60], worse than Bolivia [59], certainly worse than Central Asia, worse than a long list of countries."

The life expectancy for urban black males in Washington, D.C., is only 58. The men in Utah's Cache and Rich Counties, on the other hand, are the longest-lived in the country: their life expectancy is 77.5 years. The state of South Dakota alone, Murray adds, has a "staggering range of patterns." Men of the Pine Ridge and Rosebud Sioux Reservations in Bennett County have the worst life expectancy in the United States--56.5 years, lower than any Western Hemisphere nation except Haiti. But other South Dakota counties rank among the top 10 of the 2,077 county units studied.

Although income clearly affects longevity, "It's not the high-income urban populations like Westchester County, New York, that do the best," says Murray, "but the rural Midwest populations." The highest county-wide life expectancy in the United States (barring race) is found in Stearns County, Minnesota, where the average life span for women is 83--equal to that of women in Japan.

"Why are disparities in the United States so large compared to other high-income countries?" asks Murray. First of all, there are physiological causes. "People in Bennett County, South Dakota, die more often from specific diseases and injuries," such as diabetes, alcoholism, and suicide, he says. Then there are the individual behaviors and circumstances that surround those deaths (as well as deaths from traffic accidents, cancer, and AIDS)--like diet and physical activity, tobacco and alcohol use, sexual practices, and access to health care. Finally, there are socioeconomic determinants of behavior and environment, including income, education, and culture. These are not competing explanations, notes Murray. "They're all relevant if we're trying to reduce disparities in life expectancy."

Murray's goal is to provoke policy-makers to "figure out sensible, cost-effective things that government or others can do to decrease the disparity between, say, the Mississippi Delta counties and the people who do the best--out in Iowa, Colorado, Minnesota."

~ Harbour Fraser Hodder