![]()

Main Menu · Search

· Current Issue · Contact

· Archives · Centennial

· Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Main Menu · Search

· Current Issue · Contact

· Archives · Centennial

· Letters to the Editor · FAQs

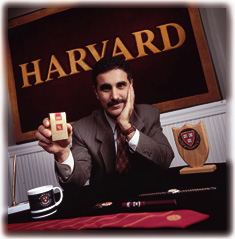

Rick

Calixto, with a rug, a watch, and other products that use Harvard's name

by license, holds one that does not--a pack of Chancellor Harvard Luxury

Cigarettes, from India.. Photograph by Jim Harrison Rick

Calixto, with a rug, a watch, and other products that use Harvard's name

by license, holds one that does not--a pack of Chancellor Harvard Luxury

Cigarettes, from India.. Photograph by Jim Harrison |

A poultry company in Korea sells "Harvard" eggs; the carton displays a mortarboard and the promise that eating the eggs will make you as smart as a Harvard scholar. A group in Taiwan opens the "Harvard Medical Clinic" and files for trademark registration of the name. A top-selling brand of cigarettes in India is called "Chancellor Harvard Luxury Cigarettes." A college in Canada proposes to establish itself under the name of "Harvard College Park." Argentinians dress up in "Lord Harvard" clothing. And an alumnus traveling in Spain finds offered for sale a grotesque cap with "Harvard University" on the front and a hank of bronze pseudo-hair affixed to the back.

Does Harvard care if Mexicans can buy Harvard refrigerators? Rick Calixto, M.T.S. '88, A.L.M. '96, program administrator of Harvard's Trademark Licensing Office, explains that confusion in the mind of the consumer is the key to trademark law, and concern about such confusion is often the determining factor when Harvard considers whether to go after someone who misuses its name. Most countries, he says, recognize 42 classes of trademark. Class 16 covers stationery; class 25, clothing; class 41, educational services. Harvard cares plenty about any unauthorized use of the word "Harvard" in class 41.

The Trademark Licensing Office employs a company to watch for uses of the name everywhere on earth. A consulting firm in Taiwan calls itself "Harvard Management" and uses a logo much like a "Veritas" shield. Harvard hires legal counsel in Taiwan to oppose the use. The University has successfully opposed names such as the "Harvard Superior Technical Institute" in Peru, but has not yet won its opposition to "Harvard Health de Mexico." A cease-and-desist letter to the Canadian founders of Harvard College Park persuaded those educators to change the name to "Harvest College Park."

Harvard wins some of these battles and loses some. Opposition can take two or three years. Lawsuits, if required, are costly.

The battles are more easily won if products officially licensed by Harvard are being marketed on the battleground. A key strategy of Calixto and colleagues is, therefore, to establish a Harvard mercantile presence in countries that tend to have the greatest potential for misuse of Harvard's name. If some legitimate Harvard licensee were selling a Harvard fountain pen in Korea, Harvard could crack those unauthorized eggs more readily. Put the other way round, if Harvard's name is widely and long misused in Korea and the University does nothing to stop it, then Harvard's rights to protect its name are weakened and can eventually be forfeited, so that it has no more or less right to use the name in Korea than the egg people.

Calixto says he is on the verge of getting licensing arrangements going in Taiwan and Korea. He is trying for them in many countries in Europe. "The name is registered everywhere," says Calixto, "but it is incumbent upon us to get a Harvard product or service on the market. Registrations can be canceled for non-use." So far, Harvard's only successful operation abroad is in Japan.

The University began its overseas licensing program in 1986 during its 350th anniversary, when demand for things Harvard was high in Japan. Soon, various licensees there were selling a wide variety of clothing and accessories--horn-rimmed eyeglasses, khaki pants, preppy blazers--with a look known in Japan as "trad," for traditional collegiate. The Harvard name did not have to be conspicuous and, in fact, typically was invisible always to all but the wearer, who was content to know that inside his or her expensive shoes lay the prestigious name of a preeminent educational institution.

The Japanese snatched up Harvard products. Royalties from licensing arrangements in that country brought Harvard $550,000 one year, says Calixto. But the economic slowdown in Japan, the bankruptcies of some licensees, and a switch in consumer preferences toward more casual styles in "Harvard" clothing have lowered royalty revenue to about $300,000 a year. Calixto is attempting to revitalize the program.

(The Japanese evidently have some taste for Princeton clothing and accessories as well. The Tigers are the only other American university with a product line in Japan. Stanford reportedly tried a licensing program there but gave it up for want of success. Calixto points out that Harvard has better name recognition around the world than any other American university: its name is abused more often than others, but the name is golden.)

Harvard's experience in Japan was catalytic, and in 1989 the University established an office dedicated to trademark monitoring and licensing. It first paid attention to what was going on under its nose. Products that use Harvard's name for sale in the United States are generally not pricey goods, but T-shirts, caps, pennants, stationery, glassware, and a profusion of trinkets. Harvard was late coming onto the field, and all sorts of stuff using the University's name was already on offer. At home as well as abroad, by registering its name and shield as trademarks and seeing to it that licensed products actually appear in the marketplace, the University is now in a position to stop someone, willy-nilly, from selling the often-proposed Harvard condom emblazoned with "Veritas." It can control quality as well as seemliness in products.

The commercialization of Harvard's name by Harvard has protective purposes, but it also, of course, makes money. Calixto's office grosses about $1 million a year in royalties, covers its costs, and turns over between $500,000 and $800,000 to the Faculty of Arts and Sciences for scholarships.

"We could make a ton of money," says Calixto, who is glad he has no pressure to do so. "We could do affinity credit cards. We could put our name on food. Many universities do. You can be buried in a casket with alma mater's name on it. Often the trademark office is affiliated with the athletic operation and is part of the big-money-making scheme." But Calixto, who did his undergraduate and graduate work in religion and philosophy and brings an almost missionary fervor to his work, is not chasing maximum profits. "As an alumnus," he says, "I will be happy if my legacy to Harvard is that I helped stop people from abusing its name."