![]()

Main Menu · Search

· Current Issue · Contact

· Archives · Centennial

· Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Main Menu · Search

· Current Issue · Contact

· Archives · Centennial

· Letters to the Editor · FAQs

Top:

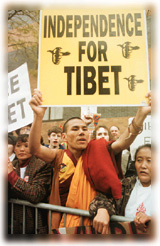

Jiang Zemin speaks in Sanders Theatre, while demonstrators outside speak

of civil rights, Tibet, Taiwan, or their joy in his visit. Photograph

of Jiang by Jon Chase; others by Mary Lee Top:

Jiang Zemin speaks in Sanders Theatre, while demonstrators outside speak

of civil rights, Tibet, Taiwan, or their joy in his visit. Photograph

of Jiang by Jon Chase; others by Mary Lee |

Chinese president Jiang Zemin's historic visit to Harvard November 1 occasioned the largest demonstrations seen in Cambridge since the Vietnam War era; they were the largest that he encountered during his trip to the United States. A stridently vocal crowd of 4,000 to 5,000 people, with perhaps as many pro-Jiang demonstrators as protestors, greeted the president's limousine as it pulled up outside Memorial Hall.

Harvard student protestors had been preparing for Jiang's visit for weeks, even before the official confirmation that he would come. The New York Times reported that the White House, fearing this, had urged the Chinese president not to go to Harvard. Yet Jiang appeared unfazed by the attention. His government had secured permission from Harvard to allow hundreds of young Chinese children from area schools to greet him. He presented a relaxed and affable face to the thousand lottery-winning ticket holders who had gathered to hear him speak in Sanders Theatre.

The speech itself, which highlighted some of China's cultural and scientific contributions to civilization over the centuries, struck many listeners as mundane and unsurprising. But Harvard scholars of Chinese social and political history pointed out afterward that references to China's history before 1949 are significant because they represent a break with the traditional Chinese Communist Party practice of ignoring the "old China." Said professor of Chinese history Peter Bol, "The implication is that after decades of trying to set the past aside, they're now saying that it matters, that they're not just a great power, but they have a cultural legacy as well."

The remarks by Jiang that drew the most media attention came after the speech, in response to a question-- submitted in writing in advance--about Tiananmen Square: "Jiang Zemin asked the West not to engage in confrontation but dialogue. However, why does he refuse dialogue with his own people? Why did the Chinese government order tanks in Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989, and confront the Chinese people?" the question read.

The "[Chinese] people," Jiang replied, "are very satisfied with achievements we have scored under the reform and opening-up program of China," adding that his government has the people's support. But the most widely publicized part of his statement was his comment that, "naturally, we may have shortcomings and even make some mistakes in our work." Pundits suggested that this was an acknowledgment that the Tiananmen Square massacre was a mistake. Chinese government officials later denied this. Jiang also reaffirmed his commitment to Chinese unity in response to a question about Tibet. Asked about his experience of American democracy--specifically the protests that followed him everywhere in the United States (the bullhorns were audible even inside Sanders)--Jiang joked that he now had "more specific understanding of the American democracy, more specific than I learned from books." After the audience's amused applause, Jiang continued, "Although I am already 71 years old, my ears still work very well," enabling him to hear the protests outside. "However," he added, "I believe the only approach for me is to speak even louder than it." A quick study indeed.