![]()

Main Menu · Search

· Current Issue · Contact

· Archives · Centennial

· Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Main Menu · Search

· Current Issue · Contact

· Archives · Centennial

· Letters to the Editor · FAQs

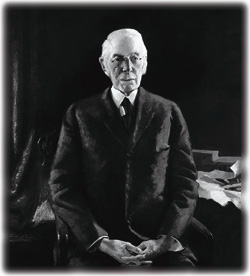

Charles

William Eliot presided over Harvard from 1869 to 1909, during an age of

discovery. A detail of a portrait, circa 1921, by Charles Hopkinson.

HARVARD UNIVERSITY PORTRAIT COLLECTION Charles

William Eliot presided over Harvard from 1869 to 1909, during an age of

discovery. A detail of a portrait, circa 1921, by Charles Hopkinson.

HARVARD UNIVERSITY PORTRAIT COLLECTION |

On October 25, with $1.65 billion already raised, President Neil L. Rudenstine set the stage for completing the $2.1-billion University Campaign, launched in 1994 and scheduled to conclude in 1999. Speaking in Sanders Theatre, he addressed a full house of Harvard benefactors, Campaign volunteers and staff, and Harvard Alumni Association officers and directors.

Noting that the Campaign "has gone remarkably" so far, while cautioning that "today's economic euphoria" should not "anesthetize any trace of yesterday's lugubriousness," Rudenstine then put American higher education in historical context and outlined the intellectual, social, and financial challenges Harvard now faces. Excerpts from his remarks follow.

If we scan the history of American higher education, it is clear that there have been two major periods of great transformation and expansion.

The first began in the latter part of the nineteenth century, and continued into the early part of the twentieth. This was our heroic, Homeric, epic age. At the heart of this ancient saga was the struggle--led by Harvard--to turn miniature colleges into emergent universities. Graduate studies were created on the Germanic model, and advanced students, in growing numbers, soon began to undertake their winding and often dolorous sojourn in pursuit of the Ph.D.

Professional school education, meanwhile, was reinvented. Serious research began to be respected. Undergraduates were suddenly placed in direct contact with major scholars. Teaching began to be more a matter of asking questions than of transmitting prefabricated answers. Dozens of new fields of knowledge were opened up.

In short, another age of discovery--a sort of academic Magellan-like efflorescence--had begun. There was a more or less unstoppable urge on the part of compulsive tycoons, middle-class classicists, pecunious as well as impecunious botanists, insatiable bibliophiles, and indomitable entomologists and archaeologists to travel, search, unearth, possess, organize, display, study, and conquer everything in sight.

If we wanted to generalize about this entire era, when so many Giants walked our Earth, we might well say that aspirations grew, knowledge grew, the curriculum grew, buildings grew, and the budget grew. In addition, at least one penetrating fundamental financial insight remained as a significant legacy, well into the future.

It was the recognition that the only way to create a major university--with museums, libraries, research institutes, and fields of learning that were important but not necessarily populous--was to endow, as far as possible, new activities of enduring importance. In that way, the total educational program and total intellectual capacity of the university could be vastly enriched and intensified without requiring student tuition and fees to bear more than a fraction of the cost.

President Eliot faced this issue early in his tenure, during the 1870s, when he wanted to enlarge the library. At the time, all the endowed book funds for Harvard's library amounted to only $10,000; and, as Eliot explained, "the whole cost of the administration and service of the Library must at present be met from College tuition fees. Endowments for these [service] departments" and activities, he urged, are essential.

Fortunately, most of our library costs are in fact now supported by endowment, as well as annual giving. As we ponder why fundraising campaigns are important, it is helpful to remember how vital these endowments and gifts are in sustaining resources as invaluable as our library system: 92 libraries of 13 million volumes, with on-line access to the total catalog as well as to a great deal of text--constituting the greatest university library in the world.

I want to shift now to that second major transformation and expansion of American higher education, right after World War II. The war demonstrated, as never before, that brains matter infinitely more than brawn. Human commitment and great courage were certainly indispensable. But the war showed us that a very great concentration of intelligence--from advanced cryptography and radar to the discovery of nuclear fission and fusion--made it possible for our own nation and others to move forward from a state of almost complete unpreparedness to the point where talent and determination, with enough raw materials and production capacity, could finally prevail.

By 1945, many people realized that what worked in war could also work in peace. So it was not surprising that education and research were at the top of our national agenda by the late 1940s. Probably the most crucial turning point here, reached by 1950, was the decision to rely primarily on our already existing major universities for America's basic research effort, rather than to build a separate government system of research institutes (on the model of some European and other countries). Since the universities represented high-quality assets-in-being, the United States had--almost immediately--a powerful, competitive, and immensely successful research enterprise under way, operating at full tilt. It soon began to produce an unprecedented number of discoveries and new insights. In fact, by far the largest number of significant breakthroughs since World War II--from the elucidation of DNA, to the creation of high-speed computer networks, to the dramatic unmasking of the top quark--all of these had origins in university-based research projects, supported largely by our federal government.

But research alone was not enough. However much we needed ideas, we certainly did not need them disembodied. As a result, the government--together with the major private foundations and individual universities--began a program to expand graduate and professional education so that there would be a steady flow of well-educated people who were prepared to take up the increasing number of positions that required new kinds of talent and leadership ability.

Therefore, when we utter the word "research," we ought to link it immediately to the word "education," at least when we are talking about a major university. The two activities, at their best, have always been linked together. The fact that they reinforce one another, at all levels, from the undergraduate college through to our executive education programs, is exactly what has made the American model of a university--and certainly Harvard--so distinctive, and so effective.

All of this may sound as if the postwar system was somehow invincible. But we know of course that it was not. Compared with the period between 1950 and 1970, flexible federal and state revenues are now less readily available, and there are many more claimants for government as well as foundation dollars. All of this represents an absolutely major change. In the new era that we have entered, there will continue to be greater constraints on external financial support, just at a moment when the need and the demand for education--as well as for new ideas and discoveries in research--are at their maximum. That is the essence of our current situation.

Our challenges and opportunities have to be seen in relation to long-term changes already taking place in society. For instance, the strong forces that have recently made our world so thoroughly interconnected are unlikely to be reversed. The Internet, instantaneous worldwide satellite connections, and rapid transportation systems are here to stay. Similar developments have produced fluid global financial markets, and have led to many more open, penetrable societies that can no longer be shielded behind iron curtains. Porous boundaries permit the quick movement of people, ideas, goods, economic capital, particles of culture--or particles of sulfur dioxide--from country to country. More societies are less authoritarian and more democratic than even half a decade ago. One possible result of all these changes is greater cooperation among peoples and nations. But another might be a growing number of close encounters that are as likely to end in collision and conflict as in collaboration.

We also know that over the next quarter century to half century, there will be major demographic changes in our own country, and throughout the world. There will almost certainly be more major centers of power. Some "minority" groups will become majorities. Women will play a greater and greater role in public life. It will be essential for people to be able to work with a widening range of fellow human beings from different backgrounds.

This will not be easy. The history of our species does not suggest that we have often managed to get on so very swimmingly together. When he was president of France, Charles de Gaulle once asked in exasperation, "How can you [possibly] govern a country which has 246 varieties of cheese?" Well, our little planet is now much further along the path toward an infinite number of anthropoid specimens, and we need to learn how to cope with all that.

What are the implications concerning an educational agenda for Harvard--through the end of this Campaign, and beyond?

First, we have no choice but to keep up our momentum in the field of international studies. If the world will be a more crowded and interdependent place, then our students and our faculty must have better opportunities to travel, explore, and learn about what is "out there." And we also need to keep up the flow of students, scholars, and professionals who come to Cambridge from abroad to study at Harvard and learn about the United States.

We need research, travel, and fellowship funds--as well as endowed faculty positions--to carry this work forward. We also need to complete the funding for, and then create, our projected new Center for International Studies. It will represent the first significant visible presence in Harvard's history of our commitment to international studies, conceived on a worldwide scale.

I believe this is also the moment for Harvard to consider locating a limited number of outposts overseas, the main purpose of which would be to facilitate research and study by the many Harvard faculty and students who now undertake fieldwork in countries around the world. We need to be able to sustain their projects over time, to build longer-term relationships with people and nations abroad, and to place ourselves more directly in touch with the societies that we study.

A second major priority is the further development of our modern information systems. It is hard to make this enterprise sound poetic. Even so, the new networks make a difference to every part of education, because they open up limitless sources of information and knowledge. These technologies, unlike some of their predecessors, are versatile and interactive. They virtually force users to take a position of command--compelling them to search, to seek, to find, and not to yield. In this way, they not only provide us with data, images, and information, but also help to transform our pedagogy, placing the emphasis on the process of framing questions and looking for relevant evidence in order to test ideas--a form of what President Conant referred to as "education by self-directed study."

As these technologies develop, faculty and students will participate more frequently in discussion groups and joint classes on-line with students and faculty at other institutions around the world. Here we can sense the obvious parallels with the transformation in international studies that I discussed earlier.

The next agenda topic concerns the question of diversity in its largest terms: how we manage to live our lives in reasonable harmony as the world shrinks, demographics change, and the pace of life continues to quicken. Unless we are willing to continue our commitment to diversity--unless we can create the conditions that will allow our students to learn directly from one another outside the classroom as well as inside--we will not have educated them fully, or prepared them to take on the role of leaders, either in our own diverse democratic society or in the international arena.

From a financial point of view, the key to ensuring diversity is need-blind admissions and need-based financial aid. Nearly half of our undergraduates are awarded scholarships which average about $14,000 per student this year--a total of more than $40 million in undergraduate scholarships alone. The system is equitable. It means that we have enough tuition income to help protect the quality of our programs, but it is also cost-effective institutionally. Most of all, it keeps Harvard well in the lead in the drive to attract the very best talent.

So our unfolding University agenda is ambitious, the needs are real, and we must keep pressing.

As we do so, let me mention one thing that lies at the very heart of what we are, and what we do. It matters that we are a residential college and university. The energy we feel in the air; the excitement and intensity that are the essence of our life here; the visible history present in our buildings; the friendships that have grown from the days and years spent together in this singular place: these depend deeply on the fact that we are rooted here, that we are a residential community whose values still echo the independent and questing spirit of our founders.

Our challenges, great as they are, are not new for this institution. Every major stride forward in our history has left us with a surprised sense of how much had been accomplished, and how much more still remained to be done.

On the occasion of Harvard's three-hundredth anniversary, in 1936, President Conant wondered about the fate of Harvard and other private universities during the coming century:

[our] universities founded quite long ago--are... [now] startlingly large and complex; their buildings and equipment are great beyond the imagination of our ancestors; their faculties and students alike have facilities never before at the disposal of any body of scholars.... Can they escape the curse which has so often plagued large human enterprises well established by a significant history--the curse of complacent mediocrity?

So far, I do not see signs of "complacent mediocrity." As we look to tomorrow, let us remember that we are, for this generation, the trustees of this very great University, and we need to reach as far and as high as we can--through calm, through change, and even through storm.