![]()

Main Menu · Search

· Current Issue · Contact

· Archives · Centennial

· Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Main Menu · Search

· Current Issue · Contact

· Archives · Centennial

· Letters to the Editor · FAQs

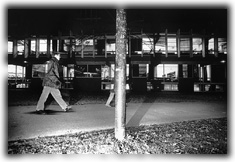

Cabot

Science Library in the Science Center stayed open all night during reading

periods last year, to accommodate the requests of night-owl scholars for

a place to cram around the clock. Photograph by Flint Born Cabot

Science Library in the Science Center stayed open all night during reading

periods last year, to accommodate the requests of night-owl scholars for

a place to cram around the clock. Photograph by Flint Born |

One morning last May, over breakfast in the Cabot House dining hall, a scolding editorial "wrote itself" in the head of Jennifer L. Burns '98. She quickly penned her complaint that reading period was eroding and submitted it to the Crimson. The editorial pages were full, but her piece was accepted because the editors felt she expressed what "everyone was thinking." Burns was concerned not about the officially designated length of reading period, currently 12 calendar days, but about the encroachment of sections, new reading assignments, and course meetings on time she believed should be reserved solely for studying.

Plummer professor of Christian morals Peter Gomes recalls that her editorial "struck a chord I'd heard before. I thought it was time to raise it in a formal way." So he asserted at a faculty meeting that reading period has been undergoing erosion (for at least 10 years, he estimates), and that its parameters should be more explicitly defined.

Just past its seventieth birthday, then, Harvard's unusual academic amenity is finding itself in the midst of an identity crisis. In an effort to clarify the history of reading period, associate dean for undergraduate education Jeffrey Wolcowitz sent Gomes a memo detailing the legislative history of the institution. The Handbook for Students currently specifies, "At the end of each term, a period of twelve days prior to the start of final examinations is designated as the Reading Period." But at its inception in 1927, the length of the period was about two and a half weeks in winter and three and a half weeks in spring. The measure called for instructors to "discontinue lectures, or other classroom exercises" except in courses open to freshmen or those which a department designated exempt from reading period. The text stipulates, though, that "courses in which section meetings or conferences are held may continue such sections or conferences." And it was also understood that "the suspension of lectures shall involve no diminution in the total amount of work...."

Later amendments to the legislation called for various refinements, such as capping reading loads at "250 to 300 pages of average difficulty." They also emphasized the optional nature of the period: a 1961 amendment referred to "the privilege of observing the Reading Period." Formulations in the current Information for Instructors and Handbook for Students echo that language, explaining that "faculty members may choose not to meet with their courses for formal classes."

Because most students merely glance at their handbooks, however, many seem unaware of how reading period is actually defined. Burns was surprised to find the description couched in terms of "choice," but says it sounded oddly familiar: "To say reading period is a privilege and not a right sounds like vintage Harvard-speak." Somewhere in the system, there is a miscommunication between administrators and faculty members on the one hand, and students on the other. "It's all well and good to say reading period is a privilege," Gomes explains, "but it becomes an expectation...there is a shared notion that it is a different kind of quality time."

The expectation is further reinforced by word of mouth from older students to younger. Burns, whose older sister attended Harvard, had the impression that "reading period was like a windfall; you could do virtually no work all semester and then submerge yourself in work." And Burns herself felt that the reading periods her first year were "a huge block of time. Now sections and new reading assignments take up the first week and destroy the period of peace."

In fact, Burns matriculated in 1994-95, the first year that reading period was set at precisely 12 days each term. Her opinion, of course, may represent one individual's changing perception as she moves from high school's temporal rigidity, to the novelty of unstructured study time, to the wearing off of that novelty. But Gomes feels strongly that "there is a student culture and lore handed from generation to generation" that fuels students' expectations and also chronicles a true phenomenon of erosion.

To Gomes, the legislative history of reading period, with its many vacillations, "records a history of the faculty's lack of consensus" about the issue. He also suggests that the policy is not clearly codified because it existed largely as an implicit code, understood in an earlier era as a gentlemen's agreement. Now that era has gone by: "We've lost a common sense of the culture around here," says Gomes. "We have a rich and diverse faculty, some of whom were not brought up in this peculiar calendar of ours with its unwritten cultural expectations."

Ultimately, the question of reading period is linked to the larger issue of academic-calendar reform. Harvard is almost unique in retaining a schedule of examinations after the two-week winter recess. The potentially stress-inducing practice is justified by the fact that students may study during reading period after (theoretically) enjoying a relaxed winter break. This ups the ante for critics of the period's trend toward shrinkage. "Reading period is trotted out whenever the Harvard calendar is questioned," notes Burns. "If they're going to use it to justify archaic practices, then it should be a real reading period." Gomes adds that if the faculty dispensed with the reading period hiatus, calendar reforms would inevitably come up.

Regardless of his own favorable feelings toward what he calls a "season of focus," Gomes says his first priority is to spark a "full discussion" of reading period policies this spring, something he has not heard in his 28 years here. "There has been no study, no systematic policy on the matter," he explains. "There have been mostly episodic discussions--mostly on the length of reading period, but little on its nature. I'm looking forward to participating."

~Miriam Udel Lambert