Main Menu · Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

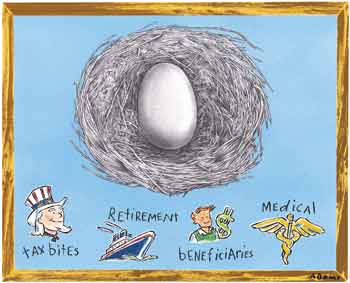

Illustration by Lisa Adams |

You've followed the advice. Over the years, you've kept an eye on your spending and put some of the money you've saved--or the money that you had your employer withhold from your paychecks--into IRAs, Keoghs, 401(k)s or 403(b)s, tax-deferred annuities(TDAs): whatever reasonable opportunities presented themselves for building up a nest egg for retirement. Now you've decided you're ready to start thinking seriously about retirement, and ready to have that nest egg start working for you. If you believe it's simply there for the taking and spending, think again. Even with a nest egg, there's no such thing as a free lunch--as the elementary pointers that follow make clear. It pays to think ahead, so you don't consume all your retirement time in managing your retirement finances.

When you need to start thinking...

Benefits consultants and financial planners recommend a four- to five-year runup to retirement, a period during which you--and your spouse or partner, if you have one--think seriously about your hopes and plans for the future. Presumably you want your nest egg to last your lifetime(s), but do you also want some of it left over for children, friends, or worthy causes? How exuberant a retirement do you anticipate? Will you move south, or travel frequently, or cultivate your garden? What's the state of your health? Working out the answers to such questions will prepare you for certain mandatory decisions you'll need to make in the months before you retire about how the benefits portion of that nest egg you've saved up actually comes to you.

Assuming a reasonable life expectancy, what should you do?

Most Americans who retire in their sixties can expect to live another 10 to 20 years, if not longer. Financial planner Frederick B. Putney, of Croton, New York, executive vice president of Brownson, Rehmus & Foxworth Inc., advises clients to think of their various retirement-income sources as different pots that often have different rules for payouts and for what you are allowed to do with the funds that remain in the pot (shift the investment mix in an IRA, for example). Putney recommends dealing with the most constrained types of income first. (Put another way, if you'd like to leave some kind of estate to your heirs, it's best to spend down your most flexible assets, like stocks, last.)

What's on the table?

Most people will need to deal with Social Security, IRAs, and pension plans.

An option for those who don't want the burden of hands-on control is to roll the money over into an annuity. According to Paul Zizzo, a senior benefits consultant at Harvard, if you're retiring at 65 or 70, and think you're likely to exceed the projected life expectancy for your age group (which generally means 12 to 15 years down the road), an annuity may make sense because it guarantees income for the rest of your life. (As a fringe benefit, IRA payouts rolled over into annuities are no longer subject to MRD requirements.) Be aware, Zizzo notes, that the annuity options offered by your employer may be more favorable than those that turn up as you shop around. And also keep in mind, says financial planner Frederick Putney, that an annuity is a rigid contract that means you've given up all rights of ownership in the assets you've signed over--so think carefully about the likely long-term stability of the institution to which you're entrusting your funds.

If an annuity's lifelong payout sounds appealing, and you're also interested in making a gift of some size to a favorite charity, inquire whether the charity itself offers annuities. You may learn about opportunities over and above the traditional version. Anne McClintock, director of Harvard's planned giving office, describes deferred charitable gift annuities as potentially a source of "great supplemental retirement income on a tax-advantaged basis." The option allows individuals who have income to save beyond the maximum allowed in a 401(k) or 403(b) plan, for instance, to set aside that additional money for retirement while saving on taxes in a different way--by making a charitable gift. If you set up a $10,000 annuity (the minimum amount at Harvard) at 60, for example, but defer payouts until you retire at 70, you will increase the regular tax write-offs for a charitable contribution and benefit the designated charity on the side.

All this assumes, of course, that you live to enjoy your retirement. But what becomes of your spouse or dependents, or other intended beneficiaries of your savings, if you die sooner than expected? Obviously, estate taxes come into play--not to mention the termination of payments under annuities keyed only to your life. As quickly becomes clear--recall the simple example above of choosing between a younger person or your estate as your IRA beneficiary--you need expert advice from tax planners, attorneys, and other advisers to sort out the interrelated operation and effects of inheritance taxes and income taxes on what you leave your heirs. (And if you are among the many individuals whose retirement assets include shares of stock, the effect of likely capital-gains taxes must be factored into the mix as well.) Frederick Putney adds a professional's wry twist to the old adage about death and taxes: Remember that tax rules and estate-tax rules are always subject to change, so give yourself the ability to make rational decisions and revised choices when that happens.

The most important thing is not to let yourself be overwhelmed and immobilized by all the rules and regulations. Retirement isn't a one-size-fits-all arrangement and you will only help yourself, and those you care about, by figuring out what works best for you. Read books and articles, look over the literature provided by banks, mutual funds, consumer groups, and professional organizations. As employers have begun to shift part of the responsibility for individual pension management to their employees, benefits departments have begun to offer more in the way of educational materials and workshops as part of their overall benefits package. Companies may hire outside consultants like the Personal Financial Education Company, in Framingham, for example, which offers a full-day program on "The Art of Retiring." Aimed at those 60 and older, the workshop discusses the best way to take one's TDA distributions, tax implications of the various options, and retirement investment strategies, as well as retiree medical options and estate-planning. To underline the importance of making such decisions in a family context, spouses are encouraged to attend.

Employers may also try a more individual educational approach. At Harvard, the staff benefits office has devised four different versions of the annual retirement statement, geared to the age and savings patterns of the recipients (as demonstrated by the presence or not of a TDA). The statements for "mature" employees (those 50 and older) provide projections of annual retirement income (adjusted for inflation) from the staff retirement plan, from your tax-deferred annuity (if you have one), and from social security at the ages of 55, 62, and 65. The aim, says Merry Touborg, director of communications for Harvard's office of Human Resources, "is to prompt more action and thinking" on staff members' parts.

Such information can help you figure out many of the questions you need to ask to plan for your own future. If you need more help with the answers, you may want to consider consulting a qualified financial planner. The Institute of Certified Financial Planners, headquartered in Denver, is one source for more information and referrals; the national organization offers a consumer-assistance line (800-282-plan) and a website "Planner Search," at www.icfp.org/plannersearch. Considering what's at stake, paying an expert for some individually tailored advice may prove one of the best investments you can make.

But remember, as with your savings, time works to your advantage: starting your retirement planning early gives you more options, to let you do the things you really want to do.

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()