Alongside candidates placed on the ballot for the Board of Overseers by the Harvard Alumni Association (HAA) nominating committee (see the slate announced January 12), interested alumni can seek nomination through a petition procedure. This year, at least six potential candidates are actively seeking to qualify for the ballot by this mechanism; the deadline for submitting the 3,000-plus valid signatures is January 31.

Updated February 4, 2024, 8:50 a.m.: None of the petitioners seeking a place on the ballot succeeded in submitting enough signatures to qualify. Accordingly, the Overseer candidates will be the slate nominated by the HAA nominating committee, as reported January 12 and linked above.

The immediate impetus for this unusually large cohort appears primarily to be criticisms of or concern about Harvard in the wake of the sharp divisions on campus prompted by the Middle East war, contending views of free speech within the community, and University leadership (now in transition, given President Claudine Gay’s departure on January 2 and the selection of Alan M. Garber as interim president). But it also stems from longer-term disagreements about Harvard’s perceived directions.

The last organized effort to secure nominations and elect Overseers as a group, under the Harvard Forward umbrella in 2020 and 2021, was prompted by several issues, but divestment of endowment holdings in enterprises associated with fossil fuel production was the leading edge of the campaign. That effort resulted in the election of three petition candidates in 2020 balloting and a fourth in 2021. In between, the governing boards changed the composition of the Overseers (as discussed further below), and Harvard Forward decided not to pursue additional nominations by gathering signatures for the 2022 balloting.

Renew Harvard Petitioners

Four potential candidates are running as the Renew Harvard slate: Zoe Bedell, J.D. ’16 (Assistant U.S. Attorney, Eastern District of Virginia); Logan Leslie ’15, J.D.-M.B.A. ’19 (founder and CEO of Northern Rock, an Atlanta-based investment firm that has interests in commercial real estate and automotive-services and parts businesses); Alec Williams, M.B.A. ’17 (who manages investment funds from Boise, Idaho); and Julia Pollak ’09 (chief economist, ZipRecruiter). On the slate’s website, under the heading “What We Believe,” the petitioners state:

Harvard’s exceptionality results not from its fame, history, fortune, or influence, but rather its unwavering commitment to seeking truth.

This Veritas ethos, emblazoned on every campus seal, supersedes all other commitments. It is the key to Harvard achieving its mission of educating the members and leaders of our society.

This mission and the commitment to truth are not self-fulfilling.…[T]his commitment also demands excellence—of Harvard’s students, faculty, alumni, and leadership. Unfortunately, we…believe that Harvard has lost sight of this core value. The time has come to recommit to this core principle.

Under the heading “What We Will Do,” the petitioners pledge to “restore leadership excellence,” “uphold free speech and academic standards,” “protect all our students,” and “remedy operational and endowment mismanagement.” Their more detailed platform critiques “demonstrably poor leadership” and advocates establishing public criteria for the next president aligned to “the responsibilities of managing a large, complex enterprise like Harvard.”

The free speech and academic freedom plank asserts that “Allowing the free and open debate of ideas was our University’s lodestar for centuries, only recently abandoned,” and advocates for principles based, among others, on the University of Chicago’s standards (for example, no institutional positions on public controversies) and untrammeled discourse: “For even nauseating ideas, we think Twain prescribes the better tonic: allow fools to ‘open [their mouths] and remove all doubt.’ The answer to noxious speech is more speech.” It also calls for “Proactively cultivat[ing] ideological diversity and contrarian thought in the Corporation, administration, faculty, and student body….”

Under the rubric of protecting all students and “their genuine diversity,” the platform contends that “administrators have become surprisingly uniform in what they value. Racial diversity is a paramount goal for any top university. So too should be diversity in socioeconomic class, ethnicity, religion, viewpoint, geographic origin, nationality, parental status, sexuality, and the myriad other factors” that shape faculty and student identities. As part of “protect[ing] every expression of identity equally,” the plan cites “even traditional identities like religion.”

Finally, the petitioners assail “institutional mismanagement,” including the claim that only one-quarter of full-time employees “directly serve” the academic mission, with more than 40 percent of staff—some 7,700 people—identified as “administrators.” They suggest that the endowment is mismanaged, comparing recent returns to public stock market returns, and implicitly critique both Harvard Management Company’s recently adopted staffing model and its performance relative to the use of alternative asset classes for investments and reported returns on those assets. Cutting bloat and boosting returns, they suggest, would lead to “universal free tuition” and a better-funded research enterprise.

In an interview, Leslie said he and Williams, friends and business associates, jointly discussed what to do in reaction to the campus upheavals beginning October 7, and around the Christmas holiday settled on petitioning. Williams had worked in the past with Bill Ackman’88, M.B.A. ’92, the hedge fund executive who has been, Leslie said, “very, very vocal” and “very courageous with many of the things he was saying.” Ackman sharply attacked the student groups who criticized Israel after the October 7 Hamas terrorist assault, assailed Gay’s subsequent responses and congressional testimony, called for the resignation of Gay and other Harvard leaders and those of other institutions, and has come out strongly against diversity, equity, and inclusion programs as practiced on many campuses. (An activist investor, Ackman is familiar with proxy contests and other tools seeking to change the management of companies he has targeted; that experience, and his advocacy for changing Harvard’s leadership, governance, and diversity policies have been widely reported in connection with the Renew slate’s petitioning.) Williams knew Bedell; and the slate was completed by inviting Pollak, who was pursuing an independent candidacy, to join.

Pollak explained formative experiences that shaped her interest in pursuing an Overseer seat. A native of South Africa, she said, she was encouraged by her mother to come to the United States for her education rather than enroll at the University of Cape Town, where she perceived the academic appointment process being undermined by consideration of applicants’ race and political beliefs. Ultimately, she said, that institution, plagued by protests, “bent to the will of the mob”—and, she said, she sees “a similar risk at Harvard.” When she enrolled in the College in 2005, she found a freshman seminar with then-President Lawrence H. Summers invigorating and challenging—an illustration of a campus where the commitment to free speech was “set at the very top” but from which Harvard, in her view, has descended to a disturbing degree. Further, as an involved student member of Hillel and Chabad, Pollak said, she was approached by members of the Harvard Jewish community who were repulsed by the campus reaction to the Hamas terrorism last October. She and fellow Renew petitioners share that reaction. Given conditions on campus, she said, it is too “easy for administrators to give in to organized, radical, very vocal groups.” By implication, representation of differing perspectives on the governing boards would give those administrators the backbone to stand up to such pressures.

Bedell said that during her studies, from 2013 to 2016, robust debate among people with very different perspectives was common at the Law School. She said that that kind of open exchange had been lost, and that her motivation for pursuing the nomination was “to restore Harvard to what it had been” in the recent past, “creating an environment where people feel like they can engage in that kind of discussion without fear of repercussions.”

Leslie said his experience in three Harvard schools over seven years revealed “a culture where people’s viewpoints are not challenged”—leading to “ridiculous” viewpoints, common on campus, that would be severely challenged in “real America.” He cited the student groups’ statement on October 7 that sought to “blame the victims of a terrorist group.” Given his experience, he said, “I could see where that would happen,” but “I was beside myself” then and as the University “really didn’t respond” in ensuing days and weeks.

He discerned a “large institution making all these errors in judgment and management,” and ultimately decided to aim for an Overseer nomination by petition. In his view, the HAA nominating process and the Overseers elected as a result have been passive instruments, a state that “promises more of the same.” The premise of the Renew effort, he summarized, is to “demand accountability.” Bedell said that the petitioners are, in one sense, outsiders (rather than HAA nominees), but all attended the University and “love the institution”—and accordingly seek to recapture qualities that she and her fellow petitioners see as having been severely eroded.

Individual Petitioners

At least two individuals are also actively pursuing signatures to gain a place on the ballot.

Attorney Harvey A. Silverglate, LL.B. ’67, a previous petitioner, is again seeking signatures for a place on the ballot. A long-time advocate of free speech on campuses (see this excerpt from his coauthored 1998 book on the subject), he is emphasizing those issues, with a twist, this year. In a statement of his candidacy, he describes then-President Gay’s testimony before the a congressional committee (which ignited a tsunami of criticism, and elicited an apology and rewording from her two days after) as “perfectly appropriate from an academic freedom point of view,” and says “the Corporation lost its nerve” and failed to back her subsequently. Regardless of one’s perspective on Gay’s presidency, Silverglate writes, the Corporation’s actions constitute a “lack of principled leadership” which he characterizes as “appalling.”

Turning to other matters, Silverglate assails the work of, and number of, “administrators,” whose ranks he would trim, with the aim of “enhanc[ing] Harvard’s academic atmosphere” and “drastically reduc[ing] tuition, enabling students to graduate with less debt.” On speech, per se, he would “eliminate all ideologically and politically based ‘training’ programs for students and faculty seeking to inculcate what has become a virtual mantra—‘diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging’” and would “abolish all ‘hate speech codes,’ restoring free speech and academic freedom.” Finally, he would undo changes in the petition process adopted in 2016 (when Harvard embraced online balloting), which significantly increased the number of signatures required to qualify for the ballot.

Sam Lessin ’05, also proceeding independently, sounds many of the same themes as Silverglate, albeit in a somewhat more ambiguous way. A self-described technology industry veteran, Lessin has worked for Bain and Company, founded two companies, was vice president of product at Facebook, and is an investing partner at the Slow Ventures venture capital firm.

His platform is partly generational: Lessin writes, “I come from the for-profit tech and finance world and have navigated charged organizations, both big and small. I represent intellectual diversity on a board dominated by older people from the nonprofit and healthcare world.” He also stresses his background as a valuable perspective given “the massive rise of applied math, computer science, and economics at the University.” About the present moment, he observes of Harvard, “We shouldn’t write it off (as most alums I know have this fall).”

Reacting to recent events, his statement says, “Harvard needs to return to its roots as an academic institution not a political one,” with “clear and consistently enforced rules” and a focus on “fostering a safe and open environment for academic free speech and protect the academic focus of the institution.”

Programmatically, he stresses ensuring “student safety”—a lapse, in his view, in the events from October 7 on. Turning to “speech culture” on campus, he is not a First Amendment absolutist in the Silverglate vein; indeed, he writes, “I would accept a decision to truly fully embrace free speech, or a culture where the administration sets standards. But you can’t pick and choose your response based on personal beliefs.” Although this appears to be embracing both sides of a very challenging debate—how to foster speech while also setting standards against harassing or threatening discourse—Lessin advocates a sharper position in an X posting linked to his Overseer campaign page:

Harvard has a nasty recent history of limiting speech on campus and instilling fear that has prevented many professors, administrators, and students from speaking up. This was never more clear to me than in running my campaign for Overseers and the number of off-the-record calls I got from people who held viewpoints they didn’t dare discuss in public.

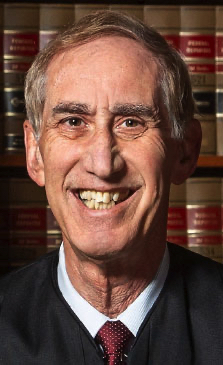

Less actively, Harris L. Hartz ’67, J.D. ’72, a judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit, has a web presence soliciting petition signatures. In a brief statement, he recalls, “As a student, I loved Harvard College and Harvard Law School.…[E]xcellence was pursued and valued; no topic was off limits; and, even though I was not in the campus mainstream, there was no reason to fear speaking my mind.” In contrast, he continues, “Too many people now see Harvard as the symbol of arrogance, intolerance, ignorance, and fear in higher education. Something has gone very wrong. The responsibility must lie with the leadership.” He seeks nomination via petition, and election as an Overseer, “to be a skeptical contrarian, willing to politely question the assumptions that can lead Harvard along a dangerous path….” He also points to “two other candidates who share my concerns”: Lessin and Silverglate.

Updated January 26, 2024, 4:30 p.m.: Hartz forwarded a current essay to Harvard Magazine. Four paragraphs are excerpted here.

I have no special knowledge of what goes on at Harvard. But the data set available to me is consistent and suggestive. The highly offensive response to the Hamas attack on October 7 was not surprising to someone familiar with the occasional formulaic statements from Harvard leadership expressing solidarity with favored victims and condemnation of disfavored perpetrators. I do not recall ever seeing a condemnation of the racism of BLM, even after the investigation by the Obama justice department completely debunked the ‘Hands up, don't shoot’ accusations about Ferguson, Missouri, which became the rallying cry for the organization. It would’ve been nice if the Harvard Law School dean (who is one of my favorite scholars) had released a statement defending the federal judiciary against false charges of racism; but that would’ve been totally out of character for a Harvard leader. If any member of Harvard’s governing institutions—the Corporation or the Board of Overseers—presented a challenge to the University’s DEI program, I am not aware of it; and the speedy appointment of President Gay, one of the program’s stalwart supporters, suggests there was none.

But the excesses of Harvard’s approach to DEI (much of which has now been declared unlawful by the United States Supreme Court) is just part of a larger problem—intolerant groupthink. The data on party affiliation among faculty members should be a red flag. The obvious explanation for the almost uniform ideology of the faculty, of course, is simply that Harvard folks are smarter and better informed than the ignorant masses. At my college reunion in 2022, one of the discussion leaders suggested that the problem with this country is that the people don’t listen to what the elites tell them anymore. I responded, with more support from the group than I expected, that the elites haven’t done such a great job recently. It is just possible that the elites could do better if they honed their ideas in debate with those of differing views. But that is apparently not happening at Harvard.…

…[T]he typical board or committee is handicapped by powerful forces that dampen discussion. Too many members see the position as a badge of honor rather than a call to action, an opportunity to advance one’s status and connections, rather than an opportunity to advance the common good. And it is far too easy to go along, to assume that if anyone else had concerns he or she would have spoken up already. Unfortunately, the process for selecting members of the Harvard Board of Overseers exacerbates these natural tendencies.…

Harvard does not need a Board that serves as a booster club. It needs a Board that will insist on bringing Harvard back to the commitment to free inquiry and vigorous debate that I loved when I was a student there more than 50 years ago. A good start would be to welcome, rather than attempt to silence, those who have loved Harvard and know that it can do better.

There may be other, more casual candidacies as well.

Some Perspectives

Although the University was (and remains) riven by differences over the Israel-Palestine war, it is the underlying issues that seem to be emerging in the Overseer petitioners’ campaigns. As President Gay and Interim President Alan Garber sought and now seek to reaffirm guidelines for broad, but civil, discourse, and Harvard schools seek to inculcate the habit of disagreeing productively, and to model such discourse, the current conditions have become a proxy for disagreements about just how open or constrained campus conversations really are. A related theme is whether commitments to diversity and inclusion have distorted speech, admissions, and even academic appointments. One can regard petitioners’ statements as addressing those matters head on, carefully raising but then skirting them, or straddling two (or more) aspects of a truly difficult set of policies and practices. But they are clearly present among the petitioners’ motivations and concerns—and clearly weigh on the minds of many community members as well. So the debate is joined in the effort to be placed on the Overseers’ ballot, and perhaps in the ensuing election.

A second set of issues emerges from seeming frustration about University staffing and expenses. That would always be a good conversation for any organization to have, especially one not constrained by the financial disciplines and constraints that apply to a private, for-profit enterprise. Harvard is a generous employer in a very expensive labor and housing market. One reason its scholars can be productive is because it invests in excellent facilities and support staff. But questions ought to be asked: whether its staffing is optimal, whether all the things it is doing ought to be done, and so on.

Some of the questions being asked this year may emerge from petitioners’ belief that some staff investments—in diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging programs, for instance—are either overwrought or are completely inappropriate.

Others may reflect a general wariness of spending on staff (the same note as a politician’s assault on “waste,” without specifying what that is, or how significant). It would probably be productive, if possible, to focus those claims further. The University does not make it very easy to understand its costs, and administrative costs encompass lots of core functions, like information technology (expanding continuously, and even more so during pandemic-driven remote instruction), mental health care (ditto), and regulatory compliance. Unpacking that further would certainly be productive.

But good information is available about tuition. It is known, for instance, that under the current College financial aid program, a majority of students pay nothing like the posted annual price for tuition, room, and board (about one-fifth of undergraduates attend free of charge now); and those who receive aid are not required by Harvard to incur any debt to attend. Real challenges do arise for the children of families from the upper-middle income ranks, who don’t receive the highest levels of financial aid and who find it challenging to meet annual terms bills that now total about $80,000. The situation differs in the professional schools, particularly for traditionally high-earning occupations in business, law, and medicine, where student use of debt is commonplace.

From those basic parameters, critics might be able to prompt productive, focused conversations, even without access to detailed financial information, about some financial goals and objectives. (No outside information is needed to consider the philosophical big issues. Even if it were feasible to eliminate undergraduate tuition, for example, doing so would reward full-pay families, which are among the highest-income families in the United States and from around the world. Moreover, the unrestricted receipts from such payments are the most flexible resources available to invest in research—surely core to the University’s mission and the source of many of its most enduring contributions to society.)

••••••

Whether these issues are engaged further depends on two steps. The first is the petitioners’ ability to secure the required number of signatures during the next week, not a trivial hurdle. The second is the change in the composition of the Board of Overseers adopted by the governing boards in September 2020: a limit on the Board’s membership so that at any given time, no more than six elected Overseers may have achieved qualification for the ballot by petitioning. Because the four Harvard Forward-affiliated Overseers now serving qualified by petition (with terms expiring in 2026 and 2027), it appears that no matter how many petition candidates qualify this year (if any), and no matter the outcome of voting by the alumni, only two petitioners could be seated on the Board.

They have not yet submitted signatures, nor qualified for the ballot, but if they succeed, it is conceivable, come May, that Harvard’s election could produce some very interesting, and controversial, outcomes.