Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

|

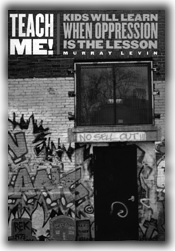

"I believe that, under the right circumstances, anyone can be taught," says Murray Levin '48, author of Teach Me! Kids Will Learn When Oppression Is the Lesson (Monthly Review Press). The book chronicles three years he spent at Boston's Greater Egleston Community High School, where most students land after expulsions from other schools or encounters with the law. Levin arrived after 45 years of teaching political theory at Columbia, Boston University, and the Harvard Extension School. He recalls that colleagues in Harvard's Afro-American studies department counseled him not to go, citing his lack of experience with high-school students in general, and with black and Latino students in particular.

Yet he went, and observed a phenomenon not uncommon in this country's secondary-school education. "There was a lot of rote learning, such as 'the American Revolution was in 1775,'" he recalls. "There was no discussion about why there was a revolution, or what its consequences were." The carpe diem attitude that pervaded the school, accounting for much of its drug culture and early motherhood, was, he decided, a result of generalized hopelessness. "Given no future, there is no reason to go to school, there is no reason to study, and there is every reason to seek pleasure," Levin says of the Egleston mentality. He wanted to give his students' education an element of relevance.

Murray Levin wanted his students' education to have relevance. DENISE PASSARETTI

Murray Levin wanted his students' education to have relevance. DENISE PASSARETTI |

What he attempted was a profoundly simple parallax of instruction. "I decided I would teach these kids, basically, what Plato taught his students," he explains. "I taught them 'what is a cause, what is an effect, what is a system, what is a process, and why is it necessary to have conflict and opposition in order to produce change.'" He asked his students to identify personally with the cases he provided for study, and "took only historical or hypothetical examples that resonated with their daily lives." Together, for example, they explored the Cuban missile crisis: "It may seem obscure," he says, "but it is a life or death situation--and so is living in Egleston Square." Levin devised a curriculum based on case studies of subjects as diverse as theories of God and the uses of symbolism in television advertising, always stressing the methodological in the class's approach. Teach Me! offers an oral history of his students' progress that documents, in their own words, the increasing sophistication of their understanding and achievement.

Over the course of three years, Levin's initial awareness of "a gigantic cultural disparity between me and the students" collapsed, gradually giving way to a respect both personal and intellectual. He both respected and loved them. Of his 20 pupils, nine went on to college or junior college; most are now employed. "One girl that I had was brilliant," Levin says. "She could have been successful at any first-class university, but she had had an alcohol problem since the age of 12. She came to me one day and said, 'There's something I want to tell you, but I don't know if I should.' Then she went on, "Last night, I dreamt that I was President Kennedy. I dreamt I was confronted with the Cuban missile crisis. And I woke up in a cold sweat because I couldn't decide which negotiating posture to hold.' It was one of the most remarkable experiences of my life. I realized I had actually reached the unconscious of these kids."

~ Kirstin E. Butler