Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

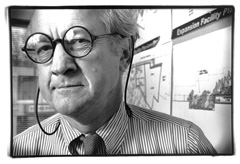

Ocean, in 1.5 Million Gallons or LessPeter Chermayeff designs aquariums to delight and enlighten. Ever wondered why Boston's Red Line is red? Peter Chermayeff chose the colors--red for Harvard, blue for the shore line, green for the branch tracing Frederick Law Olmsted's "Emerald Necklace." His firm also came up with the system's popular abbreviation, "the T" ("for transportation, tracks, trolleys, and trains," says Chermayeff), in one of their early non-aquarium projects. Current plans, for a rainforest exhibit in Des Moines and a marine-science museum in Virginia, paper the office walls behind him. Photograph by Flint Born

Ever wondered why Boston's Red Line is red? Peter Chermayeff chose the colors--red for Harvard, blue for the shore line, green for the branch tracing Frederick Law Olmsted's "Emerald Necklace." His firm also came up with the system's popular abbreviation, "the T" ("for transportation, tracks, trolleys, and trains," says Chermayeff), in one of their early non-aquarium projects. Current plans, for a rainforest exhibit in Des Moines and a marine-science museum in Virginia, paper the office walls behind him. Photograph by Flint Born |

If I could do it all again, I'd be a biologist," says Peter Chermayeff '57, M.Arch. '62. But that's just a lifelong exuberance for nature talking. Chermayeff is a man of enthusiasms who clearly relishes his work as an architect, world-renowned designer of aquariums, and sometime producer of wildlife films (Wildebeest, Lion, Baboon, Cheetah, Impala--11 in all, made for Encyclopedia Britannica Educational Corporation).

He is also president of IDEA (International Design for the Environment Associates Inc.), a firm devoted, uniquely, to the design, development, construction, and operation of aquariums and other nature-related attractions. The 22-member IDEA staff includes a variety of specialists--from marine biologists and aquarists to project managers--and consults with icthyologists, herpetologists, and environmental engineers for its projects. If a word existed to describe what, in the aggregate, they practice, it might be "aquaritecture."

What Chermayeff's filmwork and his aquariums share--aside from his love of animal life--is the presentation of "a theater, where the players are living creatures,...offering an experience through their natural behavior. That's an emotional thing, not a science lesson," he says. Reflecting this view, Chermayeff's aquariums have gradually moved away from didactic, heavily textual exhibits (such as his 1965 work at the New England Aquarium in Boston--his first major project) toward the creation of a more "visual and emotional experience" of sounds, smells, and sights grounded in a unifying thematic concept. "Visitors [to Boston and to the National Aquarium in Baltimore] were very seldom reading the text," Chermayeff recalls, "but were looking at length at the living creatures."

Rising from a harbor basin on Lisbon's Tagus River waterfront, the Oceanario de Lisboa (top), with its cantilevered roof, resembles a ship about to sail. The building, which drew 4 million visitors in the three and a half months that it served as centerpiece of the 1998 World's Fair, now operates as a permanent attraction and cultural institution that will anchor redevelopment of Lisbon's historic waterfront. A proposed mixed-use development in New Bedford, Massachusetts (bottom), centered on an aquarium, makes colorful use of an electric power plant shut down in 1992. Planners hope the New Bedford project, which includes a center for science education and economic development, a large-format-film theater, and restaurants, shops, and cinemas, will draw enough visitors to revive the city's ailing economy. COURTESY IDEA

Rising from a harbor basin on Lisbon's Tagus River waterfront, the Oceanario de Lisboa (top), with its cantilevered roof, resembles a ship about to sail. The building, which drew 4 million visitors in the three and a half months that it served as centerpiece of the 1998 World's Fair, now operates as a permanent attraction and cultural institution that will anchor redevelopment of Lisbon's historic waterfront. A proposed mixed-use development in New Bedford, Massachusetts (bottom), centered on an aquarium, makes colorful use of an electric power plant shut down in 1992. Planners hope the New Bedford project, which includes a center for science education and economic development, a large-format-film theater, and restaurants, shops, and cinemas, will draw enough visitors to revive the city's ailing economy. COURTESY IDEA |

The oceanarium in Lisbon, Chermayeff's latest project, is therefore calculated to elicit an almost purely visceral response from the visitor, under the unifying power of a simple idea: that all the world's oceans are connected, and are really, therefore, one ocean. To express this idea with fish and water, Chermayeff has placed a giant 1.2-million-gallon tank at the center of the building. Behind the tank's foot-thick clear acrylic walls, blacktip reefsharks, spotted eagle rays, and great barracuda ripple by. These and other adaptable species that migrate between warmer and cooler waters populate the tank that is meant to represent "open ocean." At its corners, four smaller habitats, of about 80,000 gallons each, represent the North Atlantic, temperate Pacific, tropical Indian, and southern oceans, each separated from the main tank by an invisible wall of acrylic. Independent environmental controls allow tropical fish to thrive at one corner, while Magellanic penguins preside at another. When the light is good, visitors can see diagonally across the tank.

"It's as if you were looking across the ocean," says Chermayeff, whose puffins and murres swim safely by as sharks cruise the background. "It's a way of presenting biological diversity and a diversity of ecosystems. The concept of one ocean is the organizing metaphor--in this case, for promoting the conservation ethic. We hope that people come away thinking about what it means to give a damn about nature."

Chermayeff got his start in the specialized niche of aquarium design by chance. In 1962, he had just graduated from the Design School, and was living in the Square ("making a film about nuclear deterrence strategy," he says). "I was feeling ambivalent about becoming an architect at all when a colleague suggested that we put together a multidisciplinary architecture firm." Chermayeff decided they needed a project first.

He went to speak to the director of the Franklin Park Zoo, and showed him how the zoo could be transformed. The director was impressed. He had no work to give, but introduced the young architects to the board then planning the New England Aquarium. "We formed Cambridge Seven with that job," says Chermayeff, who worked at that firm before resigning last year to form Chermayeff, Sollugub, and Poole with 25-year partners Peter Sollugub and Bobby Poole--who have worked with him on every aquarium project but Boston.

Though most of Chermayeff's aquariums have been designed as nonprofit cultural and educational institutions, time has proven that they also carry powerful economic benefits. They increase land values and attract visitors who otherwise would not come--lots of them. Baltimore's National Aquarium--which brings an estimated $150 million in additional revenue to the state each year--is considered a major force in stimulating the city's economic development. In Oberhausen, Germany, where a for-profit venture is underway, an aquarium will anchor a shopping center. And in the economically depressed fishing community of New Bedford, Massachusetts, with its large Portuguese population, Chermayeff is working on a sister project to the one in Lisbon that, he says "advances the state of the art in aquarium building" (see model at upper right). "What we as designers are pursuing," says Chermayeff, "is to capture the latent appreciation of people for nature and translate that into an economic engine that can contribute to the quality of urban life."

~ Jonathan Shaw