![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

Last, But Not Least |

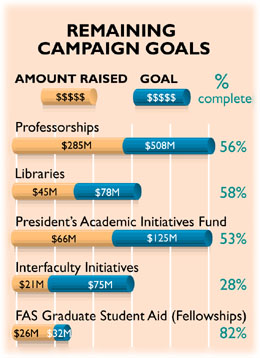

The university campaign finds itself in a curious position. By February 28, $1.975 billion had been received or pledged--close to the $2.1-billion goal set for the planned completion of the fund drive by year-end--and all the schools except one had exceeded their individual goals. Yet that one, the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, and especially the campaign's innovative funding for presidential initiatives and interfaculty programs, remain well short of their objectives. So do efforts to secure money for existing and new professorships, libraries, and fellowships for doctoral students.

It has proved hardest to attract support for priorities not associated with existing institutions or alumni. Of the $75 million sought for the five interfaculty initiatives (children and schooling; the environment; ethics and the professions; health-care policy; mind, brain, and behavior), only 28 percent has been raised. Yet other crosscutting priorities--the Asia and Latin America centers, new programs on the nonprofit sector--have attracted $65 million, suggesting that more can be accomplished for the five initiatives, particularly as they "gain prominence in their educational and intellectual activity," in the words of Harvard provost Harvey V. Fineberg.

Fineberg is playing a key role in securing the $125 million planned for the president's academic initiatives fund, now 53 percent complete. Here the fundraisers' task is triply complicated. First, the resources are intended for what the provost calls "a venture fund" expected to pay off not in the tangible gratification of a new building or an endowed chair, but in unknown intellectual rewards. Second, such funds are discretionary: the donor must trust in the future wisdom of Harvard presidents' visions of where to invest to create knowledge. And finally, Fineberg says, here, as for the interfaculty initiative funds, Harvard president Neil L. Rudenstine has focused foremost on "meeting the needs of the schools." In other words, the fundraiser-in-chief has put his own priorities last in pursuing the campaign's goals.

Fineberg insists that a president should have "some capacity to encourage initiative and experimentation for the University as a whole"--a capacity he sees Harvard lacking, given its decentralization. He ticks off needs in instructional use of technology, for the libraries, for the financial and administrative systems; opportunities for international research; and "all the domains of intellectually exciting initiatives" where Harvard scholars are "compelled" to collaborate in the sciences, in addressing social problems, and in "creating the most exciting educational opportunities for students at the borders of disciplines."

Members of Harvard's governing boards have embraced that vision emphatically. Fineberg and Senior Fellow Robert G. Stone Jr., cochairman of the campaign, have organized with present and former members of the Corporation and Board of Overseers a $20-million challenge; combined with the $40 million yet to be raised, it will complete the president's initiatives fund. This kind of discretionary, Harvard-wide support, Stone notes, "has never been [sought] in any other campaign, yet it's probably the most important part of this one, and should be a part of every future campaign."

Will the matching fund work? A $14-million challenge for undergraduate financial aid ("Completing the Campaign," March-April, page 67) was met within a month, according to Thomas M. Reardon, vice president for alumni affairs and development. With the new $20-million challenge fund highlighting the presidential initiatives, Reardon says the development office may try to fulfill other campaign goals by using challenge funds to trigger gifts for library renovations and clusters of new professorships in such high-priority areas as computer sciences.

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()