![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

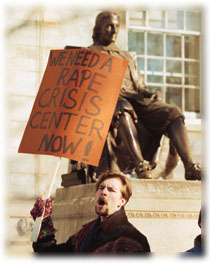

A Question of Rape On March 9, while the Faculty of Arts and Sciences deliberated in closed session the fate of an undergraduate accused of rape, student protesters from the undergraduate Coalition Against Sexual Violence (and from other student organizations: see "Students Protest Sweatshop Labor," page 67) demonstrated for improved survivor counseling and demanded the young man's expulsion. The demonstration focused national media attention on Harvard College's disciplinary practices.Photograph by Rose Lincoln |

Two "date rapes" at the College in the last year have provoked debate about Harvard's procedures for handling such cases. The victims paint a picture of a distant, uncommunicative administration that responds best in the face of unflattering publicity. Others say the College's disciplinary practices jeopardize the rights of an accused student whose case later ends up in court. Some faculty members are asking why the College's disciplinary body, the Administrative Board, should adjudicate violent felonies at all, instead of letting the courts handle them. Administrators, for their part, can say little on or off the record due to confidentiality laws.

In both incidents, a male undergraduate raped a female undergraduate. But because the circumstances of the two cases were different, some faculty argued for different penalties, as suggested by guidelines in the College's Handbook for Students, which states, "College sanctions for rape, acquaintance rape, sexual assault, or other offenses vary depending on the nature and severity of the offense, and include penalties up to and including expulsion...."

In the first incident, the young man physically overpowered his female companion. She told an interviewer from the student monthly Perspective that her face and body were bruised from the attack; she took the case directly to court, where the male student pleaded guilty to rape and was placed on probation and ordered to stay away from Harvard for three years. The faculty were expected to dismiss him April 13, as this magazine went to press.

In the other incident last spring, which only recently drew national media attention, a male student penetrated an intoxicated female friend. According to the woman, she had been sleeping, and earlier in the evening had unsuccessfully tried to keep him from accompanying her to her room and her bed; she says she had repeatedly said "No" to his advances. Later, some would question whether she introduced ambiguity to the situation by nonverbal means that could have confused the man. The precise details remain confidential.

News reports say that when the man learned that the woman was upset, he apologized, first in a note and then at meeting they arranged by the Charles River. He blamed himself, and, an informed source says, soon thereafter began describing his actions as rape.

The woman took her case first to the Ad Board, which found that a rape had occurred and recommended dismissal to the Faculty Council. When summer break delayed a full faculty vote, she decided to take the case to court.

The case proved contentious when taken up by the faculty at their first meeting, in October, and did not come to a vote until March. Even within the Faculty Council, the steering committee elected from faculty ranks, the case proved divisive. All 18 members reportedly agreed that a rape had occurred, but disagreed over the appropriate punishment. Twelve voted for dismissal. Five urged that the man be required to withdraw for five years. One abstained.

The assembled faculty did not have direct access to the full Ad Board record of the case, relying instead on descriptions of the incident by members of the Faculty Council to guide their vote, which was 119 to 19 to dismiss the student.

Photograph by Rose Lincoln |

She remains angered that the case took nearly a year to resolve. That delay, and the fact that the College describes varying penalties for different kinds of rapes, were factors in her frustration with the administration. "One should not have to be dragged down a dark alley and beaten up in addition to being raped in order to get one's assailant expelled from the academic community," she says.

The man's admission of guilt was unprecedented, according to a knowledgeable source, and this was given some weight in the deliberations. The woman says that she was "hearing from administrators about the mitigating power of [his] remorse months before I heard anything concrete about his dismissal."

James L. Sultan, J.D. '80, a lawyer hired by the defendant when the case went to court, says that his client's lack of sophistication about the legal system influenced the outcome of the case. Reportedly, in past incidents similar to this one, but where the man denied committing rape, he has typically been required to withdraw until after the female student graduates. The difference in this case was the ready admission of responsibility.

Questions have also been raised about the wisdom of the Ad Boards' demanding testimony from a defendant whose case might later go to court. The College usually defers consideration of disciplinary cases if a criminal investigation or proceeding is pending, unless both students choose otherwise. In this case, the young woman went to court after the Ad Board proceedings were over.

Sultan says Harvard should have advised his client "to consult with an attorney, and that didn't happen." Ad Board procedures specifically prohibit the presence of lawyers at hearings, and require that both students in peer disputes provide detailed, written statements of fact describing what happened. Dean of the College Harry Lewis says that "the University received no request for information or subpoena from the judicial system in this matter." But no such subpoena was necessary; standard Ad Board procedure is to share the statement of the student charged with the complainant, and vice versa. Though students in some cases have been given a written copy of the statement, this is no longer allowed, according to Thurston Smith, secretary to the Ad Board. Students may still take notes or copy the other student's statement out longhand if they choose, however. Sultan says the district attorney's office had a copy of his client's statement--essentially an admission of wrongdoing--a fact that prosecutor Marian Ryan confirms. In court, the student pleaded guilty to sexual assault and battery.

Even if confidential Ad Board documents were not exchanged between accuser and accused, they would be vulnerable to subpoena. There is no rule of law that would prevent a subpoena from being issued for such documents, says Lloyd Weinreb, Dane professor of Law. "There is no privilege for educators."

Dean Lewis says, "We always review our procedures in the aftermath of any complicated case, and I am sure this one will be no exception." Administrators have reportedly begun meeting with representatives of the student Coalition Against Sexual Violence to talk about the College's rape resources. Among the coalition's demands are improved resources for sexual-assault survivors; improved internal disciplinary practices; and better first-year education about sexual assault.

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()