![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

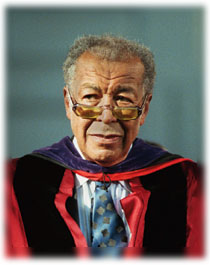

Tribute to "a Large Man" HARVARD NEWS OFFICE |

Friends from throughout the University celebrated the life and work of A. Leon Higginbotham Jr. in a service at Memorial Church on February 22. Higginbotham, who died December 14, had served as public service professor of jurisprudence at the Kennedy School and lecturer on law since his retirement, in 1993, as chief judge of the U.S. Third Circuit Court of Appeals.

As a scholar, he is best known for In the Matter of Color and Shades of Freedom, the first two volumes in an unfinished series entitled Race and the American Legal Process. At Harvard, Higginbotham will be honored by two lecture series, a new full-tuition public-service fellowship at the Kennedy School, and an undergraduate public-service summer-internship program managed by the Afro-American studies department; his widow, Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, is professor of history and of Afro-American studies.

Excerpts from President Neil L. Ruden-stine's remarks on February 22 follow.

Leon was a large man--greathearted, restless, full of purpose, wise, all-embracing. One major theme guided him throughout his life: the powerful determination to help the United States become a society where all the arbitrary, capricious, and irrelevant obstacles that interfered with the freedom and opportunities of every individual and group could and would be removed. He wanted African Americans and all others who have suffered from discrimination, from the lack of excellent education, from poverty that seems to offer no avenue of escape--he wanted all such people to experience the opening of those many doors that still too often remain closed to them.

He deliberately chose not to see himself as a prototypical individual American success story. He never thought that he had earned his way to success merely through his own combination of talent, aspiration, and hard work. He always assumed that if it had not been for the major contributions and acts of kindness of untold others, he would not have been able to achieve all that he did.

So he lived life as if it were a struggle in which he himself could never triumph, unless and until millions of others were also helped and given a chance to triumph. In his universe, no one was pressed to the periphery, in order to be dropped from sight.

When Leon organized a major conference at the Law School to mark the one-hundredth anniversary of the Supreme Court's decision in Plessy v. Ferguson, he did so because he felt that many of the policies created by the "separate but equal" doctrine sanctioned by Plessy still had great influence in the United States, in spite of the legal progress made in other cases such as Brown v. Board of Education and in the Civil Rights Act of 1965.

Leon knew that most Americans have very little direct personal memory of the civil-rights movement and of the struggle to desegregate higher education. They do not remember the fact that race was taken into account in university admissions for more than 300 years; and now, after a mere 30 years of experimenting with affirmative programs that offer African Americans some very limited degree of extra consideration, the nation is coming perilously close to saying that 30 years is enough--indeed, it is too much. Positive programs that create educational opportunities for previously excluded individuals and groups, and enrich the process and substance of education itself, are now suddenly seen as unfair, as discriminatory, and as much too costly in terms of the modest number of admissions places they absorb.

If Leon was deeply troubled about the reversals he saw around him in recent years, he never stopped for even a moment--and he remained as hopeful and exuberant as he was realistic, right to the end.

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()