Introduction

100th Anniversary Issue

Centennial Harvests:

The College Pump

The Readers Write

The Undergraduate

Harvard Portrait

Bulletin Boards

Boom and Bust: 1919-1936

War and Peace: 1937-1953

Baby Boom to Bust: 1953-1971

Century's End: 1971-1998

Centennial Sentiments

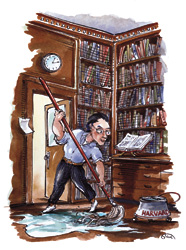

Harvard Magazine

Mark Steele

Mark Steele |

--October 12, 1946

*

Roscoe Pound has become more of a Law School legend than Story or Langdell. Now, at 77, he plans to give up active teaching, but it is safe to say he will not be idle. Pound has done everything with all his might. Born of a judicial father, he was a college graduate at 18, a lawyer at 20, a botanist at 22, a law school dean at 33. He first came to Harvard in 1910 as Story professor. For 20 years (1916-36) he was dean. It was singularly appropriate that Pound should have been the first University Professor appointed to "work on the frontiers of knowledge." To the law book and the case method, he added the sociological approach. He was the first to persuade lawyers and law schools to think of the law in terms of social interests. It was of Pound that Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., wrote to Sir Frederick Pollock:

He was said to be an authority on I know not what Latin texts. He wrote a history of Freemasonry, spent vacations in studying the topography of the battles of the Civil War, and I was told...was put into a dining club to equalize a baseball man because he knew all the scores for years....Oh dear me, it makes me tired to try to remember the titles of what he knows...

One might add that Pound could also run a mile in under five minutes at the age of 50, and in his seventies began the task of codifying Chinese law.

--February 8, 1947

*

Thirty-five years ago, the Harvard Glee Club was singing medleys and Bullfrog-on-the-Bank arrangements, with chummy mandolin selections in between. The man who led these vocalists out of batrachian bankruptcy and indirectly gave the country new standards in choral programs, conducting, and musicianship is Archibald Thompson Davison, known and loved as "The Doc." Appointed organist and choirmaster in 1910, it was some two years later that he undertook without pay to train and conduct the Harvard Glee Club. Cautiously adding good music to the mixture as before, it was the instant popularity of a Mendelssohn piece which turned the tide. He met furious alumni opposition, but in one city the local Yale Club sent him roses. It was he who introduced Radcliffe girls into the choir. This step brought a rebuke from President Lowell, afterwards his staunch supporter. Hearing the Glee Club sing before the Overseers, President Eliot told Dr. Davison that "during the 40 years I was president, this is the Glee Club that I always hoped and dreamed we would have."

--March 8, 1947

*

It would be presumptuous indeed to attempt an anthropological classification of Earnest Albert Hooton, save to remark that from vertex to tibial malleolus he appears to be unique around these parts. The leading physical anthropologist of this country, a noted wit, a skillful writer, a competent devotee of light verse, he has been a passionate partisan of "the biological reclamation of the human animal." Among his early anthropological contributions were studies of the Canary Islanders and the Pecos Indians. His latest project, the "somatotype" study of 50,000 ex-GIs, should perhaps suggest a relation between physique and temperament. But this work can hardly change Professor Hooton's conviction that what the world needs is not better machines or social institutions, but better human beings.

--April 26, 1947

*

Mark Steele

Mark Steele |

--October 9, 1948

*

The son of a millworker, William John Bingham '16 worked five years in a Lawrence textile mill himself before graduating from Exeter at 23 and Harvard at 27. Briefly he held the world's schoolboy record for the half-mile (1.59). Bingham thought he wanted to be a Texas country banker and ranch-owner; instead he came back to Cambridge to coach the Harvard track team. In 1926 he became director of athletics, and in 1932 director of physical education and athletics. His initial year was the most turbulent--when the football committee resigned, the senior members of the crew mutinied, and Princeton and Harvard severed athletic relations. "I have the naive notion," Bingham remarks, "that a college athlete is a student who, while getting an education, considers athletics an integral part of college life."

--October 22, 1949

*

The realization that the first World War had changed the U.S. role in world affairs led Perry Miller, professor of American literature, to the study of America which has been his life work. But as sometimes happens with a brilliant young man of 16 who attempts college too early, he made his discovery the hard way--by running away from home and becoming a hobo. He worked in the wheatfields, in bookstores, as a deckhand on a Tampico-bound tanker, as an oil company employee in the Belgian Congo, as a "walk-on" in Cyrano (with Walter Hampden '00). When he returned to his home in Chicago's west side, still with 10 dollars in his pocket, he was a wiser young man who knew what he wanted. Because America began in the seventeenth century, Miller began with the seventeenth century, and Orthodoxy in Massachusetts (1933), his doctoral thesis at Chicago, was the result--"the first systematic description of the New England mind from its inception to its achievement of unity and formulation in 1648."

--March 22, 1952

*

The second Samuel Zemurray Jr. and Doris Zemurray Stone-Radcliffe professor arrived at Harvard two years ago by way of California, Washington, Geneva, and other widely scattered stations, including the island of Alor. Cora A. Du Bois, a social anthropologist, has found Harvard's "aggregation of scholars" a community far easier to live with than the inhabitants of that little island halfway between Java and New Guinea, who added up to "as passionate a set of cutthroats as you'd find on Wall Street, and for about the same reasons." Alor was chosen for field work because it was unknown ethnographically, but did have a boat service twice a month, and there Miss Du Bois spent a year and a half in a community of 600 people, a day's journey from the coastal town. A far-flung series of professional positions and government posts behind her, Miss Du Bois now happily teaches and writes. She does not propose to retire eventually to Alor; concocting one's own water-system out of bamboo stems would not be, she believes, a recurrent pleasure.

--November 9, 1957

When the first Sputnik began its gyrations, the obvious man to turn to for help in tracing these phenomena was Fred L. Whipple, professor of astronomy and director of the Cambridge-Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory. Whipple had been tracking meteors and comets for many years, and giving courses about them and about interplanetary space. Satellites are the coming thing, Whipple believes; stabilized and oriented physical laboratories in a controlled orbit, they will permit astronomy to be done from above the atmosphere. Faculty, graduate students, and undergraduates are perpetually nonplussed by Whipple's astronomical neckties. His advice, if any Sputnik or any part thereof falls in your yard (a billion-to-one chance), is to grab it. Though state laws vary, it might very well become your property.

--November 30, 1957

*

Languages are as easy to learn as anything else, according to Joshua Whatmough, professor of comparative philology. The desire is the thing. Any language, he maintains, can be learned in three weeks, and it is best learned in the country where it is spoken. Words in a dozen Indo-European tongues dot his blackboard at the conclusion of a lecture. His students are required at least to learn to count from one to 10 and to know the word for 100 in Sanskrit, Greek, Latin, Gothic, Old Church Slavonic, and Lithuanian. As he paces the classroom, he obviously acts on his firm belief that the first duty of a teacher is to arouse interest, the second, third, fourth, and nth to keep it.

--February 8, 1958

*

In his first year as university professor, Paul A. Freund continues his course and seminar in the Law School on constitutional law. Next year he proposes to offer a General Education course for undergraduates, "The Legal Process," to introduce to upperclassmen not looking toward the law as a profession the method of legal reasoning, and some relations between law and other disciplines like ethics and semantics. Teaching he loves, and so will continue, but the greatest boon of his University Professorship is the time to go ahead with a projected eight-volume history of the Supreme Court. Of his years with the Justice and Treasury Departments he has no regrets; but to Washington he has "built up an immunity." A "lover of the great indoors," he asserts, solemnly enough, that being "only" a Harvard LL.B. and not a Harvard A.B., he spends much of his leisure time trying to acquire, in his words, "the essence of a liberal education."

--May 23, 1959

*

Mark Steele

Mark Steele |

--November 10, 1962

*

Neatness and precision follow William W. Howells, professor of anthropology, all the days of his life. Whether he is teaching a couple of dozen advanced scientists and embryonic archaeologists not to stand on the heads of the skeletons they are exhuming, or expounding more elementary physical anthropology to some hundreds of beginners, he wastes no words or motions. The undergraduates believe him to be "one of the best-liked lecturers in the College," who "gives clear and well-paced lectures." No pun was perhaps intended; but his neat, trim silhouette (which he attributes to his dislike of exercise) moves incessantly about the lecture platform.

--May 25, 1963

*

The current pope professor of the Latin language and literature, Mason Hammond, drives a pair of horses, as his title implies, and has done so for 30 years, when the departments of history and the classics at Harvard agreed that the traditional separation of ancient history from ancient language should be bridged. This term he offered to teach such students as desired to hear him about cities and the city state in the ancient world; against the two to 10 he thought might appear, 30-odd showed up. Next term some 200 students will listen to him bring Roman history alive--for that is a knack he has, immersing himself in a period and drawing his students with him into the pool of knowledge. T0 and from his Cambridge residence he rides his bicycle daily, despite what he finds to be curious natural phenomena: Brattle Street is uphill both ways, and the east wind that opposes him in the morning always changes to west in the afternoon.

--November 28, 1964

*

At present the department of psychology, feeling rather young and underprivileged, as against the older social sciences, is at work discovering what its members have in common, says David C. McClelland, professor of psychology. With tolerance towards all, its members work on projects ranging from the tribes of central Brazil to the cochlea of the ear. McClelland's present researches center on entrepreneurship and economic development and on the effects of social drinking. His refusal to be tied to ancient customs and procedures is paralleled by his mastery of every social dance since the Charleston, including the frug and the hully-gully.

--May 1, 1965

*

William Alfred, professor of english, once longed for the day when he could "write himself out of teaching." That was when he was doing graduate work under the direction of Archibald MacLeish, and it was as a poet that he hoped to attain his goal. Now that he might as a playwright turn his back on academe--his Hogan's Goat, playing off Broadway, is sold out through June, and his Agamemnon is due to open in October--he has no desire to do so. As a hobby he tinkers with his collection of old clocks; and some unconscious deftness--or perhaps the same touch of genius, differently directed--guides his fingers. "I don't know what I'm doing," he says, "but I make them go."

--March 19, 1966

*

The present academic year has seen marked increases in vandalism and petty larceny, the attempted theft of a Gutenberg Bible from Widener, and half a dozen bomb threats. Yet Robert Tonis, Harvard's security officer and chief of police, remains his unflappable self. Relaxed and friendly, Chief Tonis tends to be amused rather than alarmed by the escapades of students, and they, in turn, are delighted by his casual manner and his tales of 27 years with the FBI. His move to Harvard seemed like "going into paradise"; seven years later, he remains enthusiastic about the atmosphere, the people, the low incidence of serious crime, and the easy access to academic life. Each semester he audits a new course, which he chooses for the professor and not the subject. At home in Hull, the chief keeps bees, which in a good year produce a hundred pounds of honey. A graduate of Dartmouth and Boston University Law School, he likes Harvard so much that he even cheers it on against Dartmouth, to the horror of his classmates.

--January 5, 1970

*

As one chews contentedly on one's medium-rare horse steak (smothered in onions), one ought to be aware that right in the midst of Harvard is a captain of the "hospitality industry," a man who daily sees to the satisfactory filling of hundreds of academic stomachs. Charles (Chuck) Coulson, for 13 years manager of the Faculty Club and now also food director of the University Health Services, has been feeding and sheltering people all his working life. Now he and his wife and son live in a comfortable apartment in the Faculty Club, and he walks upstairs to work. Mr. Coulson says that he feels more like a member of the Club than a servant of it, and accordingly he gives high marks to Harvard for its hospitality.

--March 22, 1971

A reliable survey of the class of 1969 revealed that two-thirds of that year's seniors had smoked marijuana "more than once," and that one-quarter of those had used the whole range of hallucinogens. No wonder that "Drug Use and Adolescent Development," taught by Dr. Paul A. Walters Jr., psychiatrist to the University Health Services and lecturer on social relations, is a popular Gen Ed course. "Hallucinogens are drugs of youth," according to Dr. Walters. They are attractive to individuals with the preoccupations of youth--intimacy, achievement, self-revelation, and experience. Dr. Walters believes that drug use is a self-limiting thing, representing "time out from maturation." He predicts, indeed, that most of today's marijuana users will have switched to alcohol by their forties. "Psychiatrists," he says, "ought to make their expertise available in an educational as well as therapeutic way. Often the two are interchangeable."

--May 31, 1971

*

A Radcliffe Ph.D. is a very rare species," says Rulan Pian '44, Ph.D. '60. That isn't the only rare species she belongs to. Professor Pian is the only Harvard faculty member with a joint appointment in music and East Asian languages and civilizations, and she is only the second woman to become master of a House. South House is her new domain. Pian spent 12 years of her childhood in mainland China, but she was born in Cambridge. Her father, Yuen Ren Chao '18, taught philosophy and Chinese at Harvard, and Pian lived at home as a Radcliffe undergraduate. "I missed out on dormitory life," she says, "and I'm making up for it now." As a music concentrator, her studies of Western music were haunted by a persistent question: How can I bring all this back to China? As she expands her musical horizons and extends her presence in South House, she hopes to keep up her hobby of photo-acoustic journalism. She has videotaped and recorded musical happenings all over. As exotic as any was a Hare Krishna routine in Harvard Square.

--November 1975