![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

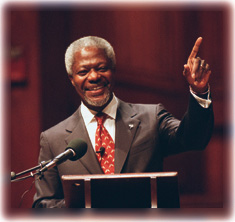

In a powerful address, Kofi Annan spoke of the global economic crisis, social justice, and equity. He was asked about Iraq during the question period. Here, he points diplomatically to two people in the Sanders Theatre balcony who had earlier unfurled a banner reading, "Welcome Mr. Annan, Help Lift Sanctions on Iraq." Photograph by Rose Lincoln/Harvard News Office

In a powerful address, Kofi Annan spoke of the global economic crisis, social justice, and equity. He was asked about Iraq during the question period. Here, he points diplomatically to two people in the Sanders Theatre balcony who had earlier unfurled a banner reading, "Welcome Mr. Annan, Help Lift Sanctions on Iraq." Photograph by Rose Lincoln/Harvard News Office |

A week and a half before the White House and Congress celebrated the first U.S. budget surplus in nearly 30 years, and the Federal Reserve cut U.S. interest rates, United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan spent a crisp September day at Harvard delivering troubling news about the state of global affairs. "What began as a currency crisis in Thailand 14 months ago," he told a capacity audience in Sanders Theatre, "has so far resulted in a contagion of economic insolvency and political paralysis."

Annan was the guest of Weatherhead professor Samuel Huntington, chairman of the Harvard Academy for International and Area Studies, which had first invited Annan to give the keynote address at a symposium last November. "Saddam Hussein was acting up at the time," Huntington says, and "at the last minute an emergency meeting of the Security Council prevented the secretary general from coming."

Annan began his day with a radio interview on WGBH's The World. Asked how he would defend the diplomacy he had used to avert military strikes against Iraq in February, Annan responded with a question of his own: "After the bombing, then what? Our objective has always been to effectively disarm Iraq....The only way you can do it is to have people on the ground. In fact," the secretary general said, "the UN inspectors have destroyed more weapons than all the bombing of the Gulf War did."

After the interview, Annan visited the Fogg Art Museum, had lunch at Up Stairs at the Pudding, toured the Barker Center with Professor Henry Louis Gates Jr., and then met with 200 students and adminstrators in University Hall at a pita-and-hummus event sponsored by the Harvard Foundation for Intercultural and Race Relations. Then, just before a dinner at Loeb House in the secretary general's honor, came the main event of his visit, the speech at Sanders. The line of would-be listeners stretched all the way back to the Yard gates, and several hundred students had to be turned away.

Annan, a charismatic and dignified presence, was praised by both Huntington and President Neil L. Rudenstine for his reforms at the UN and his efforts to achieve peace in the Persian Gulf and the former Yugoslavia. Huntington's quip that Annan might be lured to Harvard for a position as a professor after he retires from his present job was met with resounding cheers from the audience.

Annan's speech stressed the failure of economic globalization to encourage global political stability and the institution of democratic reforms. In fact, he said, a widespread belief that economic interdependencies would bring such rewards has left the world less politically prepared to deal with current crises. In some areas, economic globalization is even seen as a kind of "predatory capitalism," said Annan, and is being cast as a scapegoat for an array of problems.

In a post-speech press conference, Annan spoke of the impact that the U.S. failure to make its dues payments to the UN (totaling $1.6 billion as of August 31) has had on the institution's effectiveness in world affairs. "The first [impact] is political," said Annan. "When the United States fails to pay its dues, this provokes friends and foes alike," by "setting a bad exmple" and eroding the UN's political clout.

Furthermore, explained Annan, UN peacekeepers, whose ranks are made up of soldiers from member countries, are supposed to be paid $1,000 a month for their service. "Some of these small countries are sending their men and women into service, and we can't compensate them," said Annan. The mood in the UN toward the United States, he noted, was best characterized by a remark made by the British foreign secretary two years ago from a UN podium: "You can't have representation without taxation." Huntington, who had supported the U.S. decision to withold funds, said that Annan's reforms in the past 18 months have created a leaner UN, and now it is "time for us to pay our dues."

"Many people agree," said Huntington, "that Kofi Annan will be the most influential secretary general since Dag Hammarskjöld," who served in that position from 1953 until his death in 1961.

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()