![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

|

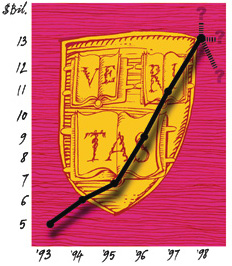

As if defying gravity, Harvard Management Company (HMC) reported a 20.5 percent total return on investments for the fiscal year ended June 30. Following the 26 percent and 25.8 percent returns earned in 1996 and 1997, this third consecutive year of strong performance--and contributions from the University Campaign--raised the value of Harvard's endowment to $13 billion. But then results began to come back to earth: citing summer shocks in financial markets worldwide, HMC president Jack R. Meyer, M.B.A. '69, reported that as of mid September, the value of the endowment had declined 10 percent, or $1.3 billion.

First, the fiscal year that was. For 1998, the 20.5 percent total return (income and realized and unrealized gains on investments, after expenses) exceeded by 3.4 percentage points the market benchmark for HMC's model portfolio, and by 2.6 points the median performance of a universe of large institutional investment funds. That brought HMC's five-year total return to an annualized rate of 19.6 percent--4.8 percentage points better than the median institutional fund, or $2.7 billion more in endowment assets than Harvard would have amassed had performance only matched the median fund's.

HMC's money managers exceeded market performance in eight of nine investment categories. Notably strong were domestic equities (about one-third of the endowment), with 1998 returns of 38.5 percent--more than 9 percentage points better than the benchmark, and sharply better than average equity portfolios, which appreciated about 24 percent, according to Meyer. Commodities investments (5 percent of the total) gained 14.5 percent in a declining market, fueled by price and volume gains for Harvard's timber holdings. Real estate (7 percent of assets) gained 44 percent, outperforming a strong market, as HMC sold several appreciated properties and the value of other assets rose. Private equities (15 percent of assets) produced a gain of 37.4 percent, primarily reflecting the sale of several companies in which Harvard was a direct investor.

The one category where performance suffered was emerging markets (9 percent of holdings), which declined 22.8 percent, slightly more than the market for comparable investments. The problems deepened after the end of the fiscal year, as Russia's August 17 default on its debt, and the abrupt devaluation of the ruble, affected emerging-market securities around the globe.

Harvard's portfolios were hurt, Meyer says, as the value of its emerging-market and U.S. equity holdings declined, forcing HMC's results through mid September to 3 percentage points below the performance of its market benchmarks--performance he cites as particularly disappointing. The pressure was exacerbated as aggressive investors (so-called "hedge funds") quickly "unwound positions" to repay loans. The forced rescue on September 23 of Long-Term Capital Management--a bond-market fund whose partners include Nobel laureate Robert C. Merton, McArthur University Professor and a pioneer in arbitrage strategies used by such investors--symbolized the sudden multibillion-dollar losses in these markets.

HMC actively uses arbitrage techniques to enhance returns, too. But Meyer says no such "explosions or implosions" have affected Harvard's more conservative portfolios. In fact, he says, although other investors' forced selling has exaggerated the decline in value of some Harvard investments, "I'm pretty optimistic we're going to get that back." Unlike hedge funds, which, he notes, may face immediate deadlines to repay clients or lenders, HMC has time to realize successful trades even as panicked investors "are not paying attention to value."

The critical element may be time. "While we are confident that our positions will pay off," Meyer wrote in the conclusion of his annual letter on HMC's results, "we are prepared for the possibility that things will get worse before they get better." And so, after a terrific bull run, Meyer reiterated his customary warning that "there will be years when absolute returns are negative and years when we underperform our benchmarks." Although it was early in a volatile new market cycle, Meyer's closing caution--that "fiscal 1999 may be one of those years"--carried special weight.

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()