In 1990, just as professor of organizational behavior Paul Lawrence was preparing to retire from the Business School, he began to notice a new leadership model gaining traction among some of his colleagues. “Agency theory” argued that managers’ prime responsibility was to work in the best interest of shareholders, he says, and was widely embraced. Lawrence thought the theory ignored employees, customers, suppliers, neighbors, the environment—every other conceivable constituency—for the sake of shareholder profit. “To maximize just one of those didn’t make sense. ‘There’s more to human beings than just making money,’” he recalls thinking. “I had a kind of visceral reaction to this.”

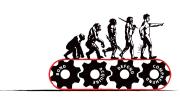

Looking not only for a better leadership model, but a better theory of human behavior, he read books on religion, paleontology, and neuroscience; histories of societies from ancient to modern American, in chronological order; and the latest science digests. Above all, he read Darwin.

In The Descent of Man, Lawrence found what he was looking for: Darwin’s description of human evolutionary history can be used, he says, to explain almost every aspect of human behavior, from religious faith, to the subprime mortgage crisis and the bond market, to the corporate corruption of politics—even the rise of Hitler. He read and re-read his personal copy, now well-worn and heavily annotated. “I thought, ‘There it is.’ It became my chief reference point from then on.”

After years of study, Lawrence published Driven to Lead: Good, Bad, and Misguided Leadership (2010), which lays out what he calls Renewed Darwinian (RD) Theory of Human Behavior. In short, RD theory posits that all human beings are motivated by four independent, innate drives: the drive to acquire (the instinctive push to obtain things necessary to ensure continuity and reproductive success); the drive to defend (the desire to ensure that what is acquired is not lost); the drive to comprehend (humans’ need to understand the world around them); and the drive to bond (the push to connect and relate to our fellow human beings). Our behavior, according to Lawrence, is a result of our brain’s attempt to maintain a balance among these four drives.

It’s a grand unifying theory that Lawrence says manifests itself in just about every aspect of human behavior, and even explicates the drafting of the Constitution. The Founding Fathers’ motivations weren’t born with the Revolutionary War, according to Lawrence, but were instead formed tens of thousands or even millions of years earlier. His “four-drive” translation of the formative conversations that led to the drafting of that foundational document is straightforward: “We need to use our creative capacities (drive to comprehend) to design a government that can strike a reasonable balance between private individual property rights (drive to acquire) and the common good (drive to bond), while guarding us against internal and external enemies (drive to defend).” At the opposite end of the ethical spectrum is the current economic crisis, which he says stems from a few bad apples with an outsized drive to acquire and no moral conscience, due to a lack of the drive to bond.

Understanding human motivation has obvious implications for the field of management. In 2008, in the Harvard Business Review, one of Lawrence’s former collaborators, Nitin Nohria (now dean of the school), and a few colleagues published the results gathered from hundreds of employees at multinational firms who’d taken a survey conducted as a sort of systematic test of Lawrence’s four-drive theory. They found that not only did the four drives explain “60 percent of employees’ variance on motivational indicators,” but that if just one drive went unaddressed, that pulled down employee satisfaction for all the other categories. The best results came when all four drives were being fulfilled simultaneously. The authors offer a comparison of home improvement giant Home Depot with smaller competitor Lowe’s: Home Depot’s CEO embarked on a campaign that emphasized individual store performance—putting the drive to acquire over the employees’ camaraderie (drive to bond)—and saw no growth in the company’s stock price. Lowe’s employed a “holistic approach to satisfying employees’ emotional needs through its reward system, culture, management systems, and design of jobs” and gained ground. This kind of Darwinian analysis, Lawrence says, could be instituted to ensure productivity and motivation at every level in any group enterprise.