Seated at a diner in Palm Desert, California, sculptor Dan Droz ’72 performs a magic trick. A Pittsburgh native, he’s here to oversee the installation of four of his pieces at the Melissa Morgan Fine Art gallery. The 72-year-old artist (and former magician) drapes a napkin over his fist and pours a packet of stevia on top. “So, for now, it’s here,” he says. Then, with an indecipherable move of his hand, he makes the powder disappear. “But if we want it to come back, just hold out your hand,” he says, leaning in conspiratorially. A tilt of the napkin, and out pours the stevia.

“In magic terminology, what you saw was ‘The Effect,’ or what the audience experiences. What I was doing was ‘The Method,’ or the technique the magician uses,” he says. “For a moment, there were two simultaneous realities, and they were totally different from one another.” He puts the napkin back on his lap and takes a bite of his omelet. “I try to do the same thing in my art.”

Since retiring four years ago as a designer and devoting himself to sculpture full-time, Droz has produced seven bodies of work in multiple mediums, gained representation in galleries on the East and West Coasts, had several solo shows, and last fall released a book about his work, Behind the Fold. He says sculpture is more a continuation than a career change. “It’s all the things I’ve always been interested in my entire life: innovating, creating new processes, and the magic of making things.”

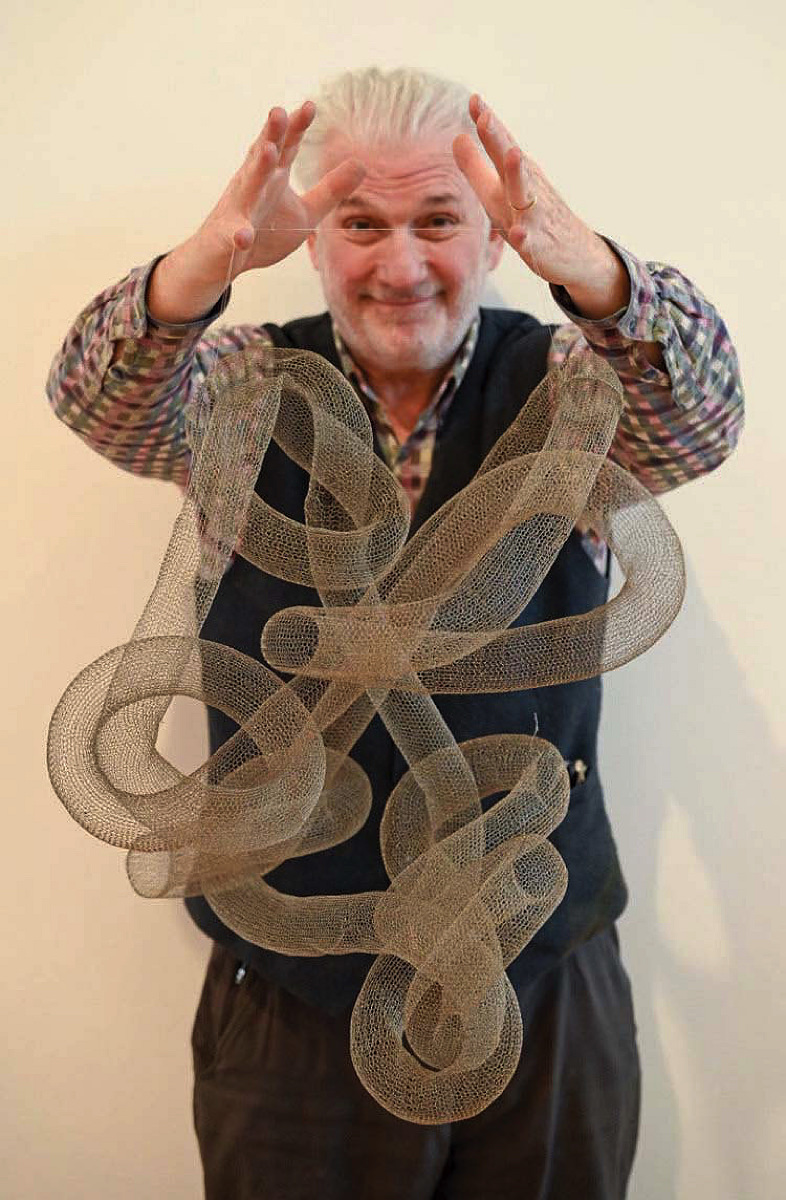

Droz makes his mesh sculpture “levitate”Photograph courtesy of Dan Droz

Droz’s geometrically abstract, often primary-colored pieces (ranging from 12-inch sculptures to a 12-foot installation on a Pittsburgh street corner) are, like their creator, inviting, playful, and a little mischievous. The massive cobalt blue piece The Gathering uses careful incisions and folding to transform a two-dimensional aluminum plane into a three-dimensional abstract sculpture of people hugging. In the suspended piece Convolutions, crocheted wire mesh—which typically cannot hold form—imagine how a window screen wilts without a frame—is shaped into a series of rigid, interconnected pipes, like a scrambled pneumatic tube system. And in Which Way, rainbow-colored glass, which normally can only be bent instead of folded, folds open like wrapping paper torn from a gift.

The Gathering (aluminum)Photograph courtesy of Dan Droz

“I grew up among tools,” he says. As a teenager, he worked alongside his father, a woodworker and a welder. In 1968, he left Pittsburgh for Harvard, where he concentrated in visual and environmental studies and the history of science, and moonlighted as a magician (“The Great Drozini”) to pay for his schooling. First as a student, then as an assistant, he studied under design faculty member and former director of the Carpenter Center Toshihiro Katayama, training in disciplines like the Japanese art of kirigami. Similar to origami, it involves folding paper into three-dimensional shapes, but in kirigami, the artist cuts the paper to add to its dimensions.

His design career started at 22, when he brought a backpack of prototypes for pepper mills, cutting boards, and serving ware to the New York Bloomingdale’s and asked to speak with a buyer. He didn’t make a deal that day, but the buyer pointed him in the right direction, and soon, H.E. Lauffer Company was distributing his goods nationally. He opened his own firm and moved into furniture design, making bunk beds, tables, and other home goods for a collection of Danish manufacturers, and in 1983, joined the faculty at Carnegie Mellon University in the College of Fine Arts.

All the while, he was building sculptures in his home studio, or “scuttling around in my basement,” as he calls it. But he knew he needed to go full-time to make the ambitious work he imagined. “I believe sculpture has the capacity to transform a space into a place. And a sculpture can be as beautiful as ever sitting in my studio, but it’s not changing the space. To do that, someone has to buy it and get it out in the world,” he says. “This is my career. This isn’t a hobby.”

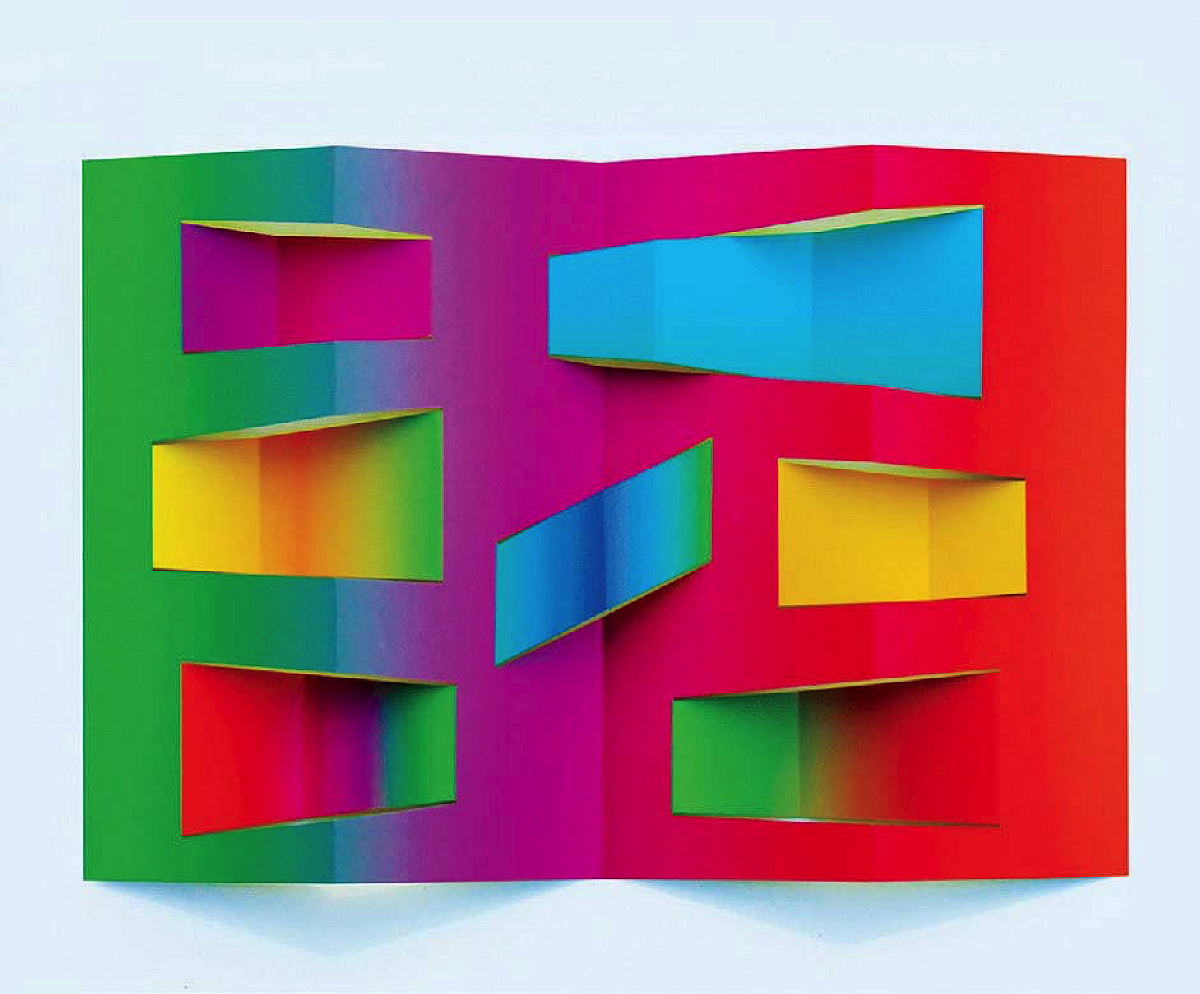

Top:Defying Dimensions (acrylic on aluminum), bottom: Which Way (glass)Photographs courtesy of Dan Droz

His sculpture-making process is highly efficient, designed to produce many pieces quickly. For works in aluminum, his most common medium, Droz starts with a large plane and scores it like one would a sheet of paper—except, instead of an X-Acto knife, he uses a computer-controlled cutting machine. Those cutouts, which he folds using clamps and elbow grease, give the pieces shape. Some rectangles he scores might later be tied to form an unlikely bow, or another cutout folded to resemble an arm jutting from the sculpture. Sculpting is usually either additive or subtractive: joining materials to make something from nothing or removing bits of a medium until only the sculpture is left. But by cutting and folding a single plane, Droz says, “My sculptures are neither.”

“Nobody is doing what Dan’s doing,” says Melissa Morgan, who represents his work in her Palm Desert gallery. “He has something to say, and he’s coming up with new ways to work with materials.” To “fold” glass in a kiln, he invented a device with torsion springs that pushes the softened material; he can 3D-print a polymer that behaves like wax for bronze-casting; and he’s developed a novel technique that enables wire mesh to hold its shape.

Though Droz readily reveals his artistic process, the effect of the art depends partly on its mystery. “I like the notion that there are important pieces of information or content that are intentionally concealed or not immediately obvious,” he says. Bright neon paint hidden behind a fold lends a work a mysterious lit-from-within look. A well-placed mirror alters a viewer’s experience of a sculpture, depending on where she stands. “I’m trying to make magic happen, to create an experience of two simultaneous realities, because that’s what our experience in the world is like,” he says. “Each of us is a very small part of the entire reality that’s going on. Even in our relationships with each other, we conceal some of the most important things about ourselves.”

After his magic trick that morning in Palm Desert, Droz finishes his omelet and heads to the gallery’s outdoor sculpture garden where his works are being unloaded. Art handlers lift the multi-colored works from the truck to rest on stands in the gravel. Droz turns to one of the handlers: “Allen, when was the last time someone offered you a hundred grand just for showing up?” Before Allen replies, Droz procures a fun-size 100 Grand chocolate bar from his pocket—his signature greeting. “I think I have about 800 grand from Dan at this point,” another handler jokes.

The candy bars—like magic tricks, like sculpture—are a way of connecting with people. Art creates a bond between us, making magic in the gap between our respective realities. “Not to be too philosophical about it, but if there’s an afterlife, I believe it’s the memory people have of me, the things we leave behind, the ideas we leave behind,” Droz says. “I want to take that memory and put it into physical form.”