The arrangements and itinerary for the election and introduction of Harvard's twenty-seventh president, on Sunday, March 11, hewed to the pattern established 10 years earlier, when Neil L. Rudenstine was chosen to succeed Derek C. Bok. There was the New York City gathering of the University's Governing Boards, convening this time on the sixty-fourth floor of 30 Rockefeller Plaza, in the conference facilities just beneath the Rainbow Room. The 18 (of 30) members of the Board of Overseers in attendance granted the Corporation's request to hold an election. The Corporation's vote was taken. The nine-person search committee described and discussed with the Overseers the considerations bearing on its recommendation of Lawrence H. Summers, Ph.D. '82, who then addressed the group and fielded questions. The Overseers then conferred, and unanimously concurred.

The result was announced minutes later, at the start of a celebratory luncheon, by Sharon Elliott Gagnon, Ph.D. '72, president of the Overseers and a member of the search committee. President-elect Summers spoke briefly. Robert G. Stone Jr. '45, Senior Fellow of the Corporation and chairman of the search committee, thanked all involved, as did Summers. Meanwhile, out in the halls and in surrounding rooms, University officials worked the phones, formally releasing the news that the Crimson had broken nearly 48 hours earlier (see "The Summers Scoop," page 60).

From then on, the day became a twenty-first century affair. Airline reliability having deteriorated during the past decade, particularly between La Guardia and Logan, the traveling party--Gagnon; Corporation members Hanna Holborn Gray, Ph.D. '57, and James R. Houghton '58, M.B.A. '62; Summers; Stone; and Joe Wrinn, Harvard's director of news and public affairs--departed around 2 in two limousines, bound for a private jet, parked in New Jersey, made available by Houghton, chairman emeritus of Corning Inc. En route--followed by Crimson reporters in chase cars--the president-elect began granting interviews to the New York Times, Boston Globe, and Wall Street Journal.

On arrival at Loeb House, the former presidential residence on Quincy Street, Summers shook the hand of every student and Harvard police officer he encountered on his way inside, and then repaired to an office to make more phone calls, confer with Harvard staff, prepare for a news conference and, shortly after 5, meet with University News Office staff for photographs and a brief interview. Reporters and camera crews passing down the hall to the ballroom could munch on cookies or slake their thirsts with beverages prominently including Diet Coke, the president-elect's favorite drink.

As several dozen news personnel set up their equipment or settled into chairs in the Loeb House ballroom, a communications network unimagined a decade earlier hummed into life. During the afternoon, a message from Stone, with directions to the official news release on the University's website, was dispatched to the 103,848 alumni whose e-mail addresses were on file in Harvard computers (89,029 of the e-mails got through). The news office took digital photographs of the press conference and posted them and a transcript of the formal remarks and press questions on its website that evening. This magazine digitally videotaped the proceedings and posted excerpts on its website. And faculty and staff, arriving at their desks Monday morning, found a broadcast voice-mail message from spokesman Wrinn alerting them to the news.

|

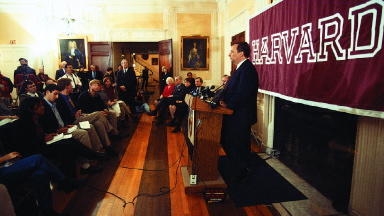

| President-elect Lawrence H. Summers meets the press March 11; to his right, Robert G. Stone Jr., Neil L. Rudenstine, Sharon Elliott Gagnon, James R. Houghton, and Hanna Holborn Gray listen in. Presidential pair (right): newcomer Summers gets a pat from incumbent Rudenstine |

| Photographs by Stu Rosner |

Technology aside, certain traditions were still respected. Shortly after 5:30, Summers was introduced by Stone, who first thanked "faculty, students, staff, alumni, and friends" of the Harvard community for participating in the search. He then hailed Rudenstine for his "extraordinary and selfless devotion to Harvard," making it possible for his successor to "assume the leadership of a strong and vibrant institution that is very well positioned for the future."

Stone then outlined the president-elect's scholarly achievements and government career. Following his undergraduate education at MIT and his Harvard doctoral work (the latter coincident with three years of teaching at his alma mater), Summers spent a year on the staff of the president's Council of Economic Advisers. He then began teaching in Harvard's economics department in 1983, having been offered tenure at the startling age of 28. Four years later, he was elevated to the Ropes professorship of political economy. Beginning in 1991, there followed a decade in Washington, D.C., at the World Bank and the Treasury Department, culminating in his service as Secretary from mid 1999 until this January.

Stone then said, "Larry embodies a rare combination as one of the most respected scholars and one of the most influential public servants of his generation. He is a person of extraordinary academic distinction with a deeply rooted understanding of the University and its purposes, as well as extensive leadership experience on the national and international scene. His many admirers within and beyond Harvard know him to be someone of exceptional energy and creativity. Someone who inspires people to do their best work. Someone who thinks incisively and imaginatively about how complex institutions work and how they change. He is a gifted teacher, a valued mentor, and a thoughtful human being, passionate about education and ideas and full of curiosity about fields beyond his own. We enthusiastically welcome him back to Harvard and look forward to his leadership in guiding the University wisely and ably into the future."

Summers thereupon took public possession of the Harvard presidency in a casual, conversational way: "It's good to be home," he said. "I accept."

With thanks to Rudenstine for extending Harvard's excellence "in many spheres," Summers expressed "a feeling of excitement and exhilaration" about leading the University in its "central mission [of] education and scholarship." Drawing on his experience, Summers dismissed the notion that the ivory tower is "remote," observing that "the ideas of scholars, whether regarding the molecular basis of life, the dynamics of global markets, [or] the way we experience literature and art, profoundly shape the world in which we live."

The challenges facing Harvard, he said, ranged "from ensuring that undergraduate education is the best that it can be, to advancing in the forefront of increasingly expensive scientific research, to fostering cutting-edge thinking and teaching regarding the professions, and carrying forward the torch of learning and the humanities." Alluding to both the growth of the endowment and Harvard's recent land purchases in Allston, Summers noted that the University "now has both the resources and the room to innovate and grow," as a "global economy that is increasingly shaped around knowledge" makes this an exciting era for Harvard and for higher education. To prepare for his new responsibilities, he expected that, "before I do much more speaking I will be doing a great deal of listening to the members of this community." (For his complete remarks, see www.hno.harvard.edu/specials/summers/transcript.html.)

Two dozen chanting and drumming student protesters outside provided background music for the news conference, bringing into this bit of the ivory tower messages from the world beyond: complaints about Harvard's wages, sweatshop production of insignia clothing, and the secrecy of the search process.

|  |

|  |

| An animated figure at the lectern, Summers appeared to enjoy the give-and-take with reporters, answering questions about his administrative style, town-gown relations, distance learning, and more. | |

| Photographs by Stu Rosner | |

WBUR wanted to know about Summers as an academic administrator. ("There are...similarities between government and a university. In both cases, there is a complex, multifaceted mission....The essence of leadership...is forming consensus on the right direction and working to ensure that the...people in an institution are as strong as they possibly can be.") The Washington Post, naturally, sought his perspective as a "Beltway insider." ("My heart has always been with the work of thought and ideas. That's been the base of my career, and that's the world I've always wanted to come back to"--now with broader knowledge about "the forces shaping or changing our global system" and "leadership in complex organizations.") When a Harvard Independent writer asked about "the secret process that produced you," Summers cheerfully replied, "It was my parents who produced me," and then observed, "I think it would ill become me at this juncture to criticize the selection process."

With that the briefing ended, at 6:07, and Summers was off to a Crimson interview, dinner, and his first formal group appointment on campus. In a gesture as homespun and symbolic as the first two sentences of his remarks, he met privately with representatives of the Undergraduate Council to learn about their experiences with professors, academic advisers, and more.

The next day was filled with more interviews; calls to Cambridge and Boston government officials; a tour of Massachusetts Hall and introductions to staff; lunch at Loeb House with the Corporation, deans, and vice presidents; and a walk through Elmwood, the president's house. But Summers was also on the telephone seeking more detailed information about College teaching and advising. And so began energetic learning, through many channels, about what he called a "very complicated" and diverse place.

Downriver, MIT's website gave the appointment almost as much prominence as did Harvard's. Beside a 1975 senior-year photograph of the amply bearded Summers, the lead article claimed him as "the first MIT alumnus to head Harvard." Another story noted that he was the second MIT faculty member to become Harvard president. The first was chemist Charles W. Eliot--whose 40-year presidency, beginning in 1869, was the seminal era in Harvard's transformation from a regional college into a modern research university aiming for leadership among institutions of higher education worldwide.