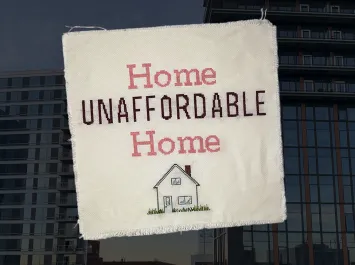

Behind the Scenes: Digging into the housing crisis

Managing editor Jonathan Shaw takes a deeper look into the factors driving unaffordability.

News coverage of the astronomically high cost of housing tends to emphasize short-term factors such as sudden shifts in interest rates, or pandemic-precipitated moves among young people. These are among the proximate causes of unaffordability right now. But why, for example, has a two-bedroom row house in Greenwich Village increased a thousand times in value since 1947, when consumer prices rose just 13 times? In previous short articles, I’d had the opportunity to explore specific aspects of the housing crisis. But I wanted to dig deeper into some of the underlying reasons for the housing shortage, because it is so fundamental to family well-being.

Harvard has an extraordinary resource in the Joint Center for Housing Studies, which is devoted to aggregating and analyzing housing data—and that is where Managing Director Chris Herbert generously gave me a crash-course in the most salient dimensions of the housing affordability problem. The data show a dramatic increase in eligibility for rental assistance during the past two decades, for example, that outpaces by more than a factor of four the increase in the number of households actually being helped—an unmistakable sign that it will not be possible to subsidize a way out of housing shortages. That means finding ways to deliver housing less expensively.

At the outset, I thought the focus of the article would be on finding ways to reduce construction costs. But it turns out that the single most important factor driving up the cost of housing is instead the price of land, which increases dramatically the closer it is to the centers of the country’s most economically productive cities. We can’t make more land, Herbert told me, but we can make better use of it by allowing greater density.

Glimp professor of economics Edward Glaeser is known for eloquently advocating the virtues of living in cities, as he did in this 2019 Harvard Magazine podcast. He has therefore thought deeply about impediments to urban growth. By comparing housing affordability in various U.S. cities, Glaeser has found that those with the most restrictive zoning also tend to have the most expensive housing.

Zoning can be a valuable tool, but as Williams professor of urban planning and design Jerold Kayden explained to me, zoning has not always lived up to its promise. Kayden is founding director of the Master in Real Estate program at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. Invaluably, he was able to point me to alumni who have been writing and speaking about the housing affordability problem for years. And he described the tension between competing values whenever land use is being discussed: how to reconcile the virtues of historic preservation or environmental protection with affordable housing development? Plenty of people care about all three.

Sustained support from readers has enabled Harvard Magazine to write about housing at least a dozen times in the past two decades—laying the foundation for more inclusive consideration in our recent feature about this complex and difficult social problem.