Behind the Scenes: “A Right Way to Read?”

Staff writer Nina Pasquini examines the state of literacy education and the gaps between research, policy, and practice.

As I began to report on literacy education earlier this year (see my feature, “A Right Way to Read?”), it became clear how hard it is to connect research—like the scholarship at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education (HGSE)—to policy and the classrooms where millions of American schoolchildren spend formative years. Educators and policymakers aren’t always able to access research that’s behind paywalls or opaquely written. And as information about research filters through legislatures, school boards, and media outlets, it can sometimes get misrepresented.

There is a broad consensus on the urgency of improving literacy in the United States: children lost months of reading achievement during the pandemic, and the most recent National Assessment of Educational Progress found that two-thirds of students could not read proficiently. But debates about the right way to address this alarming reality have been fierce—and, unfortunately for learners, polarized.

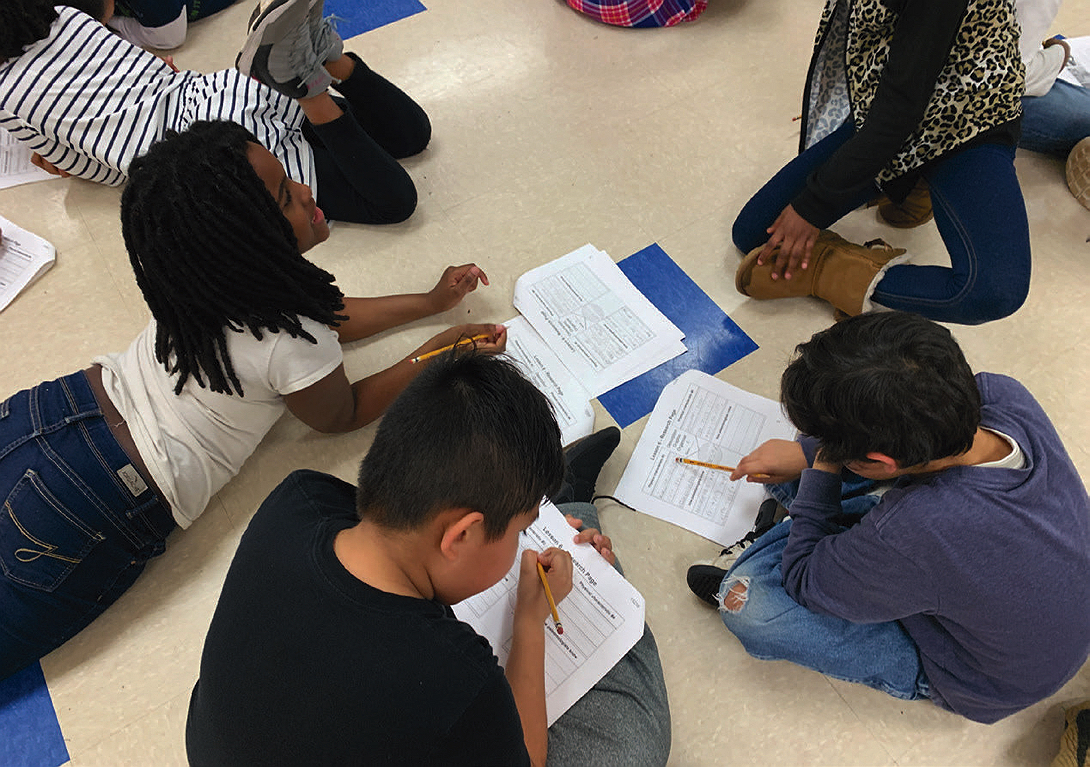

I spoke with experts at HGSE about what research has shown about how students learn to read. But I was also able to spend many months hearing from HGSE alumni about how this research has—and hasn’t—shaped classroom practices. A former fifth-grade teacher in Texas recalled that some of her students could sound out words but not understand them; a reading interventionist in the same state told me that some teachers were not paid for state-mandated training. Locally, I met with educators in Cambridge Public Schools, who shared that district investment has enabled them to implement literacy reforms more effectively.

I also had the opportunity to speak with students and parents. A fifth-grader with dyslexia told me he has not only struggled with reading for years—but has also started to associate school with frustration. And students who previously found reading difficult shared how their worlds opened up once they could understand the words on the page.

These vivid examples illuminated the consequences of the gap between research and practice. To improve literacy, district leaders and policymakers have increasingly turned to the “science of reading”—a broad, multidisciplinary body of research about how children learn to read, which has found that phonics, oral language, and comprehension are all crucial. But as this research gained attention, it was sometimes oversimplified: to some stakeholders, “the science of reading” became synonymous with phonics only. As a result, some reading reforms have heavily emphasized phonics while forgoing other necessary structural changes, such as compensated professional development and systems that track the effectiveness of new materials.

After my reporting, I spent weeks weaving together the dozens of interviews I conducted and numerous studies I read. Throughout this process, I received many rounds of invaluable feedback from Harvard Magazine editors. I’m grateful for the time and support I had to not only cover the important research happening at Harvard—but to speak to so many educators and students about its stakes. This work wouldn’t be possible without donor support, and I hope it has contributed to closing the gap between research and practice at least a little.