Behind the Scenes: Medical robotics changing lives

Managing editor Jonathan Shaw dives into the latest medical robotics research taking place in Harvard’s labs, and interviews the patients who have had life-changing experiences as a result.

Imagine yourself a successful young lawyer working in a Washington, D.C.-area firm. You are 33, with the bulk of your working years ahead of you, until one day you unexpectedly suffer a debilitating series of strokes. Years of rehabilitation and speech therapy follow, but more than a decade later, walking is difficult, because it requires constant focus.

This horrifying scenario is not hypothetical—it actually happened to Bryant Butler, when an abscessed tooth was repeatedly misdiagnosed as a nasal infection, as he recounted to me during an interview.

Bryant was generous to share with Harvard Magazine the details of his ordeal, and the benefits he has since derived from a wearable robot developed at the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. He says the device had finally helped him walk with confidence again.

Getting to the crux of the efforts of the inventors and engineers developing medical robots, whether for surgery or to help patients struggling with mobility, came from pulling on a thread. The story began with an article in the scientific literature that provided an overview of the use of robots in medicine. What got my attention was the fact that 80 percent of the papers in the field had appeared in the last 10 years. Ten had been published in 1990, compared to more than 5,200 in 2020.

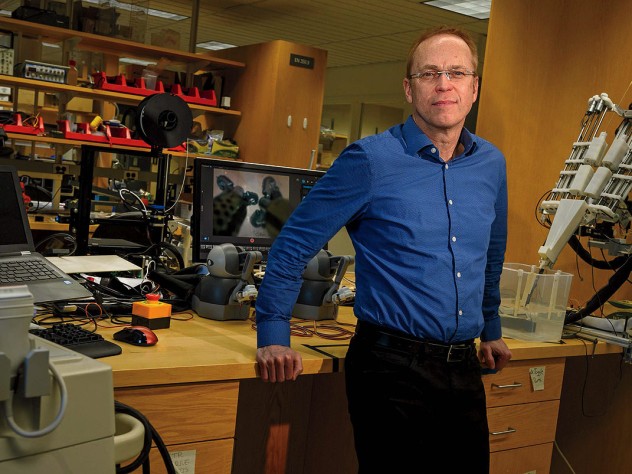

I sought out an author of this overview, Pierre Dupont, a professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School who runs a pediatric surgical research lab at Boston Children’s Hospital. He pointed me to other Harvard colleagues working in this area, and in particular to Maeder professor of engineering and applied sciences Conor Walsh, who essentially invented the entire field of wearable robotics. I toured his lab and others at the new Science and Engineering Complex in Allston, and learned about a recent breakthrough his team had made with a Parkinson’s patient who would periodically freeze in mid-gait while walking. By wearing a special robot (a different type than the one worn by Butler), he could walk without stopping. Just a little nudge from this lightweight robot kept him moving.

While some of the extraordinary engineering (intravascular robots clearing arterial plaque, for example) captured my attention initially, it was the shared focus on patients among all these engineers that ultimately resonated most strongly. Applied scientists like these are driven by discovery—but have the extra motivation and satisfaction of seeing patients benefit from their research in their labs, and in real life. As Walsh put it, every iteration of a device is driven by the desire to “understand if what we are doing is helping people or not.” And thanks to reader support, scientists like Walsh trusted me with direct access to their work and labs, because they value Harvard Magazine’s reporting and reputation.

Read “The Medical-Robotics Revolution”