Arriving

I left Philadelphia for Radcliffe by train on a September morning, family all gathered at the station. I promised my stepfather I wouldn't take taxis. But if I hadn't hailed one at Back Bay station, I might never have found the place. Not having been there, I didn't realize Cambridge was across the river from Boston. The taxi driver was much amused.

That day, I became a Cliffie. It wasn't exactly a term of endearment. Even the sound of it, primitive and diminutive at once, lacked the patrician smoothness of Wellesley, the gothic resonance of Bryn Mawr, the directnes ment. Even the sound of it, primitive and diminutive at once, lacked the patrician smoothness of Wellesley, the gothic resonance of Bryn Mawr, the directness of Smith. Cliffies, the received wisdom was, wore dirty trench coats, had stringy hair, and traveled everywhere slouched under the burden of the requisite green bookbag. They were too smart and worked too hard. Too many of them in a class, the grumble went, raised the grading curve.

The 'Cliffe

Cliffies lived at the 'Cliffe. Steep? Slippery? Something to hang onto desperately or throw yourself off? Not for us those Harvard entries and suites with bathrooms and fireplaces. We lived on corridors floored with practical brown linoleum, in rooms so small that one might have to climb on the desk to get to the upper bunk. The bathrooms were communal, with wooden cubbies for personal effects, clearly expected to be minimal. If you wanted a bath, you had to wait your turn while someone splashed away or lay soaking in blue jeans she was shrinking to form fit. There was one full-length mirror next to the door to the staircase, which discouraged vain contemplation of self in new black dress from Filene's Basement.

Telephones for incoming calls were housed in the broom closets, a precarious perch amid pails and sour-smelling mops. Cursing the darkness, you tried to avoid an avalanche of cleaning products and hit the button for the right line lest you bumble into some passionate conversation. At least the broom closet was privateone outgoing telephone was in a laundry room that doubled as a toilet.

Signing Out (And In)

We had curfews: 11 o'clock, with a few precious one o'clocks per term. We had to sign out in the evenings: name and destination. The epic record of our comings and goings was the sign-out book, a huge loose-leaf binder. We were supposed to be specific about our plans, but "UT" (University Theater) covered a multitude of possibilities. Although we were given keys to the front door early in our careers, when we came back at night, the sign-out book was set out on a chair like a Bible on a lectern, for us to sign in. Some member of the House committee (elected from those who, unbelievably, wanted the job) kept watch, as my friends and I found out when one of us came back 15 minutes late (and tipsy). We were still downstairs when she blundered in and decided she should just sign in "One o'clock." Next morning we were all called up before the House committee. We had been caught. No permissions for the next two weekends for the five of us.

Gracious Living

Unlike other women's institutions, we didn't have daisy chains or trees to sing to, but we did have something called "gracious living." It said so in the handbook. I connected it almost entirely with our housemother, Mrs. Locke. Mrs. Locke lived in proud disregard of the two mingy little ground-floor rooms she had been allotted and had crammed with the furniture and artifacts of a big house. If she gave you tea, it was in bone china cups on a silver tray. She also handed out aspirin for headaches, Coricidin and orange juice for colds, and some miraculous herbal concoction for cramps. She led us into dinner and out again for demitasses in the big living room. I think we stood up when she left. She presided over formal dinners when we had candles and sherry and could invite facultyusually just a section man or two who, overwhelmed by all the attention, would become either silent or hysterical.

House Jobs

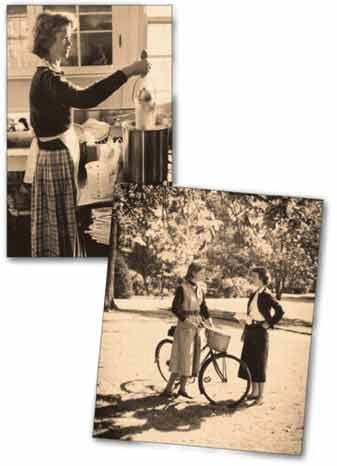

We all had to do them, to remind us, perhaps, that there would always be domestic obligations. You could run the huge, steaming locomotive of a dishwasher in the kitchen, you could wait on table, or you could do "bells."

Most people preferred "bells." "Bells" sat in a little corral in the front hall, alertly monitoring undesirables and running the switchboard. I never liked the job. An undesirable might slip by while I was doing my Hum 2 reading or I might inadvertently cut off someone's important call. People's love lives could become very intense. Besides, if you couldn't get a caller to leave his name, you had to write "Mr. X" on the pink slip. That meant you might be quizzed for hourswhat words did he use? what kind of voice?especially if "will call again" was not checked.

Waiting on table"waiting on," as it was calledinvolved a lot of standing around in a little starched white apron. I preferred the camaraderie of the kitchen, presided over by Mary O'Brien, whose mantra was, "If you always eat this good, girls, you'll be lucky." She also told me I'd be late for my own funeral.

Physical Education

Our first encounters with the Radcliffe Gym were the infamous naked posture pictures and the fire-ropes test. If you didn't die of embarrassment at the former, you might die in earnest at the latter, which required you to shinny down a rope from the gym's balcony. All dorm rooms were equipped with these ropes, and rumor (false) had it that you had to go down them at every fire drill. The rationale for the photographs was murkier.

Freshman year included a physical-education requirement. The jocks among us did the team sports like field hockey and basketball. I spent a lot of time poring over the list of offerings, but, in the end, chose archerynot quite as romantic as fencing, but a cinematic sort of skill nonetheless. Perhaps I could shoot apples off the heads of some of the more annoying members of my Soc Sci section. Also, the bull's-eye targets were set up on the Quad, which cut down on travel.

I was convinced that I could send my arrow winging, clean and unerring, to the bull's-eye. I was to be disappointed. I certainly never hit the bull's-eye, and usually failed to hit the target at all. When we lined up at the requisite distance and shot, the arrows rained everywhere. It was a wonder that we didn't take out some hapless passerby. I gave up on archery and rounded out the year with something called body mechanics and with modern dance.

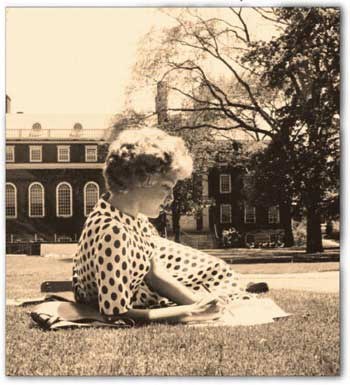

Travels in Cambridge

Thoreau, doing all that prissy traveling in Concord, was one of the things I didn't like about English 7. But I'd have to say I traveled widely in Cambridge. We all did. We were at Harvard. We belonged in the Yard and the Square, too. I suppose it might have been nice just to roll out of bed and stroll up from one of the River Houses, grabbing a coffee on the way. Garden Street provided no coffee shops or other entertainments, although the repetitive slog did become a sort of meditation. Still, the brick sidewalks could be treacherouswet leaves in the fall, ice in the winter.

A bicycle was faster, if you could maneuver through the baroque Cambridge traffic. I can still see the horrified expression of the driver whose trolley I just missed because I was carrying books in both hands and couldn't use the brakes. And all this had to be accomplished in skirts; we could wear pants only if the temperature fell below a certain point. That happened, I remember, but it was during a blizzard and I fell in a snow drift three times en route to the Square.

We must have walked an astounding number of miles in a term. To the Square, to the library, back to the Quad for lunch (eating in the Square got expensive), to the Square again. We walked in the cold and the rain and the winter dark. Darkness had its dangers, like lurkers in the rhododendrons near the library gate. We were admonished not to cross the Common alone at night. In fact, it was in the daytime that I regularly met the flasher, a sprightly little man who shouted "Whee!" as he flung open his raincoat.

Friends

An older, shabbier Cambridge was a happy backdrop for friendship. There were those long walks down Garden Street on October afternoons, cups of tea at the Bick between classes. If you'd been studying in the library all of a winter afternoon and a friend came, tapped you on the head, and suggested the Window Shop, you could wander down Brattle Street into a dream of Vienna, with authentic hot chocolate, whipped cream, and waitresses with accents, in dirndls. You could sit there soaking up the atmosphere as the early darkness came down. I liked upper Mass. Ave. by the Quad, too. In those days, it was pleasantly run downlots of junk shops, where we would go to prospect for things like a brass lamp in the shape of a cockatoo riding on the back of a turtle. Or we traveled in packs up to The Midget, a deli cum restaurant, where we could sit in a booth and nurse a coffee for hours. And talk. And talk some more.

It was a heady experience to be somewhere where everyone was smartand most were smarter than you wereand you didn't have to keep a lid on it. If I occasionally wondered how some of the people I knew got into Harvard, I never wondered about anyone at Radcliffe. Quirky they might be, even eccentric: I knew someone who kept an illegal German shepherd in her room and someone else who took her plants round the block in a little red wagon to give them air. It was all part of the pattern. It was a relief to come home at the end of a day and just sit for a while in someone's room, listening to Ella or Odetta and eating prune-whip yogurt. And not talking.

The World around Us

We occupied an odd niche in time, more fifties than sixties, I suppose. Still, events were on the turn. As a dorm, we voted, with great seriousness of purpose, to rent a television for the Nixon-Kennedy debates. Russian was the popular language: learning it bespoke a sense that a thaw in the Cold War would come if only we could talk to each other. People began to talk about the Peace Corps and VISTA. Joan Baez was singing at Club 47. The future looked bright and hopeful, like the sunny colors in the new Marimekko shop on lower Brattle Street.

If you "flicked out" to the Brattle, however, as we often did, you met a darker and more sinister reality in the films of Fellini and Bergman, the Paris of Jean Paul Belmondo's Breathless. Europe was apparently a more complex place, but then Henry James had explained all that for you.

Leaving

I took my last English exam in Longfellow Hall. It was much better taking exams at Radcliffe, because you were not proctored. No one stood behind your chair or followed you to the bathroom. If you wanted to take a break and walk down to the Square, you simply handed in your blue book temporarily. I turned in mine and went to sit for a little while in the garden next to Appian Way. The irises were in bloom; it was a perfect early summer day. I knew I was writing a good exam. I was happy and sad. It was almost over. Time to jump off the 'Cliffe.

Perdita Buchan '62, a Bunting Institute Fellow in creative writing from 1972 to 1974, has published two novels. Her short fiction and personal essays have appeared in national magazines. She lives in Ocean Grove, New Jersey, and teaches in the writing program at Rutgers University.

Photographs courtesy of Radcliffe Archives, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University