Editor's Note: Nicholas Dawidoff '85 has just published The Fly Swatter: How My Grandfather Made His Way in the World, a richly detailed portrait of Alexander Gerschenkron, the economic historian who was a member of the Harvard faculty from 1948, when he was appointed an assistant professor, until 1975, when he became emeritus after serving for 20 years as Barker professor of economics. Excerpts from chapter 10, "The Great Gerschenkron," follow.

Dawidoff describes the deep attachment his grandfather (nicknamed "Shura") felt for the University, and therefore much of the book concerns Gerschenkron's life as a scholar and teacher. "Being a professor at Harvard enabled Shura to become fully himself, allowed him to decide who he wanted to be and to fashion himself into that man," Dawidoff writes. As a member of that community, Shura found himself in the greatest country in the world, "the finest thing" in which was Harvard, the best part of which, in turn, was the economics department. Here was both "a realization of personality and a reconstruction."

Dawidoff homes in on the apotheosis of that personality and experience, Shura's involvement with his graduate students. "In Shura's day," he writes, "Harvard took a three-in-hand approach to its graduate economics curriculum, with all 60 first-year students obligated to study theory, statistics, and history. That is not precisely correct. The real requirements were theory, statistics, and Gerschenkron. Various professors taught various courses in theory and statistics. Shura's lone offering was 'The Economic History of Europe,' and every single student pursuing a graduate degree in economics spent two semesters taking it."

During the course, "Particular scrutiny was given to England, Germany, France, and Russia, with additional emphasis directed toward whatever other countries Shura had become taken with at the moment. (There was a Bulgarian interlude, an Italian intermezzo, and a two- or three-year period when all roads to commercial development suddenly swerved through Stockholm.)... Shura presented the growth of capitalism as a broad historical narrative with a teeming dramatis personae of nobles, guild officers, plowmen, coal miners, census takers, engineers, entrepreneurs, clerks, sea captains, and financiers. On any given day he might tell the students about a newfangled horse collar that improved pulling performance, spice traders who grew rich importing powders that disguised the foul taste of spoiled food, or an order of medieval French monks who devised one of the world's first large-scale industrial plants. Or he might describe the bizarre spectacle of the countries on opposing sides in the Crimean War continuing to trade in each other's currencies even as their armies exchanged bullets. (The lesson there was that the world of stocks and bonds recognized no boundaries.)"

If all that was not enough, Shura as he lectured "suggested a union catalogue's worth of 'supplemental reading'...additional titles that tended to have been written in teenaged centuries." And all that was merely prologue. The real teaching, and the real demands on students, began only when it came time to write papers, to commit to the scholarly life (with its promised rewards and its threatened exile), and to undertake original research under Shura's fierce tutelage. Most of the time the process worked, producing what Dawidoff describes as "an extraordinary succession of successful students who are now among the most prominent and influential economic historians of our time"—scholars who have served on the faculties of preeminent universities around the world, and whose books fill the shelves of research libraries. "What no doubt would make Shura happier still," his grandson notes, "is that today students of Gerschenkron's students are telling Gerschenkron stories"—and there were plenty of them.

Each semester in Economics 233 there were two formal requirements for students: a written exam and a 30- to 40-page term paper. Shura was not much for exams. Before giving them he would announce, "If the test is not fair, it will be graded fairly. And vice versa." As Shura saw it, exams were the sort of pointless exercises in maintaining poise under pressure that only an Austrian Herr Doktor Professor could love. Term papers, however, he said were "sanctified." He rhapsodized about past students whose hard work and imaginative thinking had led to the creation of original works of scholarship. To impress upon his new charges what a "wonderful opportunity" the term paper was, he required all 60 of them to schedule an individual meeting with him in his office to have their topic approved.

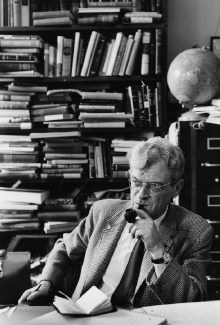

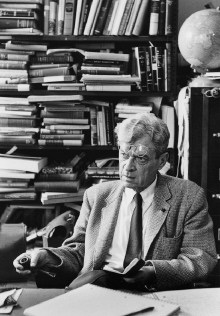

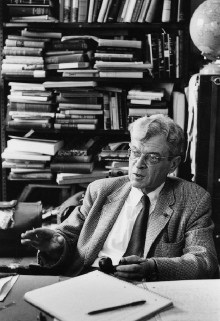

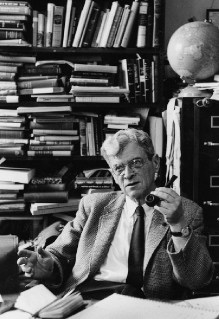

|

The scholar in his milieu: Gerschenkron roamed across languages and eras, commanding vast knowledge of economic history. |

Photographs of Alexander Gerschenkron courtesy Harvard University Archives |

"Let me clear off a chair for you," Shura would say when a student presented himself in the doorway to discuss a term paper topic. Then Shura emerged from behind his desk, always moving at a leisurely gait so that the student could take a long look around. "The thing that was very impressive was his office," says a former student, the economist Albert Fishlow. "It was all designed to reflect the importance of the commitment to scholarship."

If the student proposed a paper Shura thought unpromising, he would get a distant look in his eye. "Oh," he would say. "Yes. Well, you know, I had a student once. Can't remember his name exactly. He wrote on that earlier, I believe. But to be sure, you ought to contact him directly. He's out in Waco, Texas. As I say, can't recall his name, but you can find him out in Waco, at the Waco economics department." If, however, he heard something he liked, usually it took no more than two sentences to hurl Shura into action. "Yes!" he would cry, leaping from his chair. "You might look at this!" and he was across the room in a blur, extracting a book from one of the densely planted shelves and flipping to the page he wanted. A moment later he was venturing deep into the pastures near the window to secure another volume. Then he was charging through the thickly papered meadows behind his desk, where he stretched high above his head for a third. Although these forays took him all over the office, he was a farmer who knew exactly where every straw was in his haystack, so they consumed very little time. Watching him go, the students congratulated themselves a little for their perspicacity in selecting a subject in which their teacher saw such potential.

In the spring, the students were welcomed back into Shura's office to discuss their second-semes-ter paper. When Bill Whitney [Ph.D. '68, now ombudsman at the Wharton School] came for his appointment, Shura told him how highly he'd thought of his first-semester paper. It was so good, Shura said, that they really ought to drink to it. He poured Whitney his first-ever glass of brandy. Whitney had come to Harvard from a farming community of 900 people in northwestern Iowa, intending to study straight economics. Whitney had arrived in a state of nerves. Now he was sitting in the office of Shura surrounded by books written in languages he couldn't identify, sipping an exotic liquor. Shura was an exceptional host, topping off Whitney's glass, asking him sympathetic questions, and, in the time-honored posture of those who wish to flatter their guests, leaning toward Whitney just a little as they chatted. Whitney had begun to feel warm and good, to feel that it was "a bigger world than I had known," when Shura hinted that he ought to consider a career in economic history. At that moment Whitney realized that this was exactly what he wanted to do with his life. He wanted to study under Gerschenkron and some day to have an office full of books of his own, and to know what was in all of them. In other words, Whitney says, "I was hooked."

In one way or another they all were. "The course was where he made decisions on who would do well and who would fall under his spell," says Paul David ['56, Ph.D. '63, a professor of economics at both Stanford and Oxford]. "He was very shrewd." When Shura encountered someone promising, he "attracted" him, as he explained to another professor. In other words, he used his large personality to cultivate a large infatuation with his little field. Operat-ing much like a confidence man, he was telling the students a tale, serving up a convincer, and then making the mark. As in any really sophisticated grift, most of the students never believed that anything untoward had been done to them.

Perhaps nothing had. Much as they all came to Harvard wanting to study straight economics, many students also worried that they were condemning themselves to a dismal science. Now here was Gerschenkron telling them that it didn't have to be that way. "We were drawn to him," says Henry Rosovsky [Jf '57, Ph.D. '59, LL.D. '98, Geyser University Professor emeritus]. "When you think about it, economists in those days were not, by and large, fascinating human beings. They were accountants with unusual mathematical abilities. Salt of the earth, many of them, but not the most interesting people. He and his subject were so much more interesting than other economic subjects."

Every time Shura lectured he felt he was guilty of that most unforgivable sin for an economist, the willful denial of modern technology. "[Lectures] are Middle Ages," he complained not long after he retired from teaching. "They are altogether pre-Gutenberg. It's not an adult way. The adult way is for students to sit on the appropriate part of their anatomy" and ready themselves for a provocative group conversation. Shura contended that "what goes through the student's mind during the discussion, the need to articulate his opinion and to defend it against the other students and the instructor, are things that are likely to continue to ferment and are not easily forgotten." Shura was sure such a system was superior because he'd tested it. His graduate seminar was a weekly economic history colloquium that in its day was well known throughout the American academy as a master class for scholars.

Every Wednesday evening, eight to 12 graduate students and Shura met around a long table in a room adjoining his office to discuss a paper that everyone had been given to read the previous week. Usually the students wrote the papers, but there were also submissions by eminent economic historians Shura invited in from as far away as Europe to share their recent work. These guests were the only outsiders he permitted. This, says H.R. Habakkuk of Oxford, was because "feudal lords do not allow other lords inside their court." Whoever wrote the week's paper had a few minutes to explain himself. Then the floor was open. The best way to explain Shura's views on seminar protocol is to say that they closely resembled his notions of a good dogfight....

Every Wednesday evening, eight to 12 graduate students and Shura met around a long table in a room adjoining his office to discuss a paper that everyone had been given to read the previous week. Usually the students wrote the papers, but there were also submissions by eminent economic historians Shura invited in from as far away as Europe to share their recent work. These guests were the only outsiders he permitted. This, says H.R. Habakkuk of Oxford, was because "feudal lords do not allow other lords inside their court." Whoever wrote the week's paper had a few minutes to explain himself. Then the floor was open. The best way to explain Shura's views on seminar protocol is to say that they closely resembled his notions of a good dogfight....

A typical seminar might find Marc Roberts ['64, Ph.D. '70, now professor of political economy in the Faculty of Public Health] presenting his paper measuring the effect of the steam engine on the eighteenth-century British coal industry. Roberts had spent weeks deep in Widener Library looking through Parliamentary documents, engineering reports, and engineering journals, counting up how many steam engines there were in England at different points in the century and then calculating how many bushels of coal various models of engine burned until "I knew more about steam engines in England at that time than anybody on the planet." All the research was used to demonstrate that the steam engine did not markedly influence the growth of the coal industry. From these statistical observations, Roberts ventured into an assessment of the relative value of the steam engine as it grew more expensive, and more efficient, over time. Then the discussion began....After only three minutes Roberts had to concede that "my argument was in pieces." The others saw that he had muddled a fundamental conceptual problem in microeconomic theory—whether capital is physical or financial—and they were prompt with their imprecations. "It was just us," says Paul David, "so we could be completely open and we didn't feel we needed to be polite. We were very hard on each other. The seminar was the place where people showed Gerschenkron what they could do. The reason it worked was because of his ability to elicit individual commitment from students to win his approval."

The strange part was that there were never any signs of this approval. Week after week Shura took his seat and puffed his pipe, a silent master looking on as his feral apprentices clawed at each other's ideas. He did not interrupt. His expressions did not change. Reactions from him were so rare that the students spent hours trying to interpret the sparse flickers and nods he gave them. Sometimes his tongue strayed into his cheek. Consensus had it that this meant disapproval. That was, in fact, the consensus for just about every twitch he made.

Only with the day's session about to end did Shura stir into motion. As the students fell silent he emptied and cleaned out his pipe, filled it with fresh tobacco, tamped it down with a silver tool, extracted a match from a little wooden box with a spring-loaded lid and a top decorated with a European pastoral scene, fumbled with the match until he got the bowl lit, took a couple of long puffs that made a strange echoing sound, stared around the room, and then finally offered a comment. Invariably it was succinct; once in a while it was also delphic. After a debate about how to quantify external costs beyond market measures, he began by saying, "You know, in my heart of hearts I would like to believe that the externalities were positive, but the brain is a more important organ than the heart." The students decided that meant that, while speculation is fine, it is only a pleasant prelude to the backbreaking job of locating unassailable proof....There was also the day when he crowed that some documents from the Ottoman Empire had been translated into Bulgarian, "so now we can all read them!"

Did he really mean that? Nobody knew. With his students he was so elusive, always a man removed from the fray. Some evenings after the seminar, a couple of students would be invited back to the office for a postseminar sip of (Spanish) brandy—"the laying on of hands," one of them called it. Yet whether or not this was any kind of reward was never clear. Red Sox fans rather than the most promising economic historians tended to be invited.

Every few years something happened that overwhelmed Shura's aura of stately remove,...[such as on] the memorable evening in 1958 when Shura himself gave the paper. His subject was Bulgarian production, and in the week preceding the seminar the students prepared to take on their teacher with a feverish sense of purpose. Albert Fishlow [Ph.D. '63, now an adjunct professor at Columbia, and a former faculty member at Berkeley and Yale] and Paul David spent so much time scrutinizing Shura's work they hardly slept. "We wanted badly to catch him out," says David. Neither of them could read Bulgarian, but to their joy, one day they discovered that Bulgarian statistics were available in French translation. That they could read. Mining the documents carefully, Fishlow and David found what appeared to be—oh, ecstasy!—some Gerschenkron errors. When the seminar met, with much deference they pointed them out and then gleefully sat back to see what he would do. "He congratulated us," says David. "But then he told us, 'Alas, the paper's already gone to the printer.' We never laid a glove on him." Saving face that way couldn't have been completely satisfying, which is perhaps why, when Shura later learned that Fishlow and David had culled a French translation for their Bulgarian statistics, he made a great display of outrage, thundering at them that if they'd wanted to do an honest job, they should have learned Bulgarian.

|

A gathering at the Harvard Club of New York, in the mid 1960s, for the presentation of a festschrift. From left to right: Peter Temin, Paul David, Herbert Levine, Gregory Grossman, Henry Rosovsky, Albert Fishlow, Joseph Berliner, and Robert Campbell surround Gerschenkron and his wife, Erika. |

Courtesy Henry Rosovsky |

Shura's students were young men trained on the frontiers of contemporary theory and mathematics. By applying the most sophisticated modern methodological and data-gathering techniques to the study of the past, they would change the field of economic history. Their approach would become known as the new economic history, and they would be dubbed the cliometricians—a neologism that links Clio, the muse of history, to measurement. Truth be told, there was a lot they could teach Shura. Yet his effect upon them was such that he made what they knew seem almost beside the point....

"I've thought about what made his seminar work throughout my own teaching ca-reer without being certain," says former student [C.] Knickerbocker Harley [Ph.D. '72, now professor of economics at the University of Western Ontario]. "I don't know how he did it. Somehow he created a sense of high purpose we all felt. There was a scholarly standard. It struck me that the content wasn't as important as the fundamental idea of the honesty and the worth of scholarship. It didn't matter that on technical stuff he was useless. He was an exemplar of intellectual inquiry. There was this sense that you were striving for something that had to do with quality and integrity, and when you got it you'd know it."

Many of the students sensed this: Shura had higher ambitions for them than the mere mastery of an area of economic history. He was forming them as scholars in his own image. "By a process I still don't understand, the man set an elevated critical tone that prevailed," says Peter McClelland [Ph.D. '67, professor of economics at Cornell]. "Even within Harvard that seminar was special. People would say, 'Alex has nothing to do with it. If you had a tape recorder you'd find he says very little.' True enough. But the fact is that he was there. The man was a presence."

It all amounted to an education in character....Greatness, Shura implied, was always possible, but only possible if you made it possible. Everything was up to you.

|

Relaxing at Gerschenkron's home in Francestown, New Hampshire, around 1966. Clockwise from left: Edith Sylla, Joanne McCloskey, Erika Gerschenkron, Alex Gerschenkron, Don McCloskey, Knick Harley, Peter McClelland, and Ann Harley. |

Courtesy Richard and Edith Sylla |

Shura saw the years his students spent in the seminar as their own coming of age novel. Turning graduate students into scholars was, he once confided to another professor, all a matter of "intelligent planning." They came to him young, innocent, and promising, and by the time they left him they had been fully formed as men. Along the way Shura made it his obligation to provide his students with the difficult experiences that seasoned them as people of the world. The great care with which he conceived these narratives of experience is evident in the two-paragraph letter of recommendation for a teaching position at the University of California at Berkeley he wrote for Albert Fishlow in 1960.

The letter began as a panegyric, a paragraph of praises culminating in Shura's declaration that Berkeley could not "have a better man than Fishlow for the [job.]" In the second paragraph Shura took it all back. "Let me also issue a word of serious warning," he said. This "excellent man of very great promise is also a very young man; he is not fully mature; and he still has a great many things, both very important and not so important, to learn." The 25-year-old Fishlow needed to "achieve a high standard of scholarly perfection in producing a large literary work," to master more foreign languages, to read widely in foreign literature to achieve a worldy perspective, and, finally, to "shed a certain coarseness in both manner and thought. All this," Shura said, "requires time." The strong implication was that Berkeley should allow Shura to finish the forming of Fishlow before offering him a professorship. That Fishlow was the best candidate in his field for the job was beside the point.

Fishlow was not, of course, privy to the letter at the time, yet years later when he learned of it he was not surprised. "He set himself up as a model that we tried very hard to emulate," Fishlow says. "What was so powerful about his model was that he never stated the standard; he embodied it. The phenome-non was 'Look at me. This is what it takes to be a first-class scholar.' He was extraordinarily shrewd in his ability to choose students who he knew would be responsive to him. At the time I knew he felt there was more I could absorb, and what I most wanted was his feeling that I'd done my job right."

...For his dissertation, Fishlow had decided to study the role of railroads in the growth of the American economy. Shura approved the topic, and with that it became "your thesis." Fishlow's dissertation took him seven years to write, during which Shura never once consulted with him about it, just as he avoided speaking with any of his students about their dissertations. "The simple explanation is that he didn't give a damn," says Peter McClelland.

"But that doesn't mesh. Clearly he cared about his students, their ventures, the life of the mind in economic history. So why didn't he give direction from first to last? He felt the thesis is your work which you present to the profession to qualify for membership. It was a matter of integrity. He didn't believe in touching up somebody else's work. I remember a year I'd prepared to teach a course in American economic history. I came in to discuss it with him. He looked shocked. 'Peter,' he said to me, 'if it is important for you to defend what you teach to me, I have to defend what I teach to somebody else. I have no intention of defending what I teach.' I see this as his dedication to freedom of inquiry, and giving you the freedom of your own pursuits."

The education of Albert Fishlow took many forms. In1960 Fishlow was working well on the railroads and finding himself increasingly puzzled by his mentor. Whenever he had business in Shura's office, Fishlow would see the tray of brandy glasses sitting on the typewriter table behind the desk. He knew that some students had been fed this nectar, but for Fishlow, just as there was no thesis advice, there was never any brandy either....

Shura took it upon himself to referee some of the most private aspects of his graduate students' lives, including their marriages. He came down heavily in favor of wives. To [one student's] wedding he sent a short letter to be read aloud that said: "...I distinctly prefer married students. They are much more stable." About offspring he was far less enthusiastic....In 1960 Fishlow and his wife Harriet had their first child. Six months later Harriet was pregnant again. As soon as she was showing, Fishlow heard from Shura. "He almost tried to suggest that this was a little excessive," says Fishlow. "'You have to be careful and pay attention to what you are doing,' he told me. He said I should be paying attention not to accumulate large numbers of children while I was doing my serious dissertation work."

Shura took it upon himself to referee some of the most private aspects of his graduate students' lives, including their marriages. He came down heavily in favor of wives. To [one student's] wedding he sent a short letter to be read aloud that said: "...I distinctly prefer married students. They are much more stable." About offspring he was far less enthusiastic....In 1960 Fishlow and his wife Harriet had their first child. Six months later Harriet was pregnant again. As soon as she was showing, Fishlow heard from Shura. "He almost tried to suggest that this was a little excessive," says Fishlow. "'You have to be careful and pay attention to what you are doing,' he told me. He said I should be paying attention not to accumulate large numbers of children while I was doing my serious dissertation work."

To a degree, Fishlow could see the point. He had been an impoverished student for years, living in a shabby little apartment with no bathroom sink, conditions he found much less tolerable with the prospects of multiple infants to bathe. He decided he owed it to his family to make more money. So, with his dissertation draft nearly complete, Fishlow applied for the job at Berkeley. And, despite Shura's letter of recommendation, Berkeley made Fishlow a fine offer. "I had the two children and was desperately trying to finish my dissertation by September, when I was due to be at Berkeley," he says. "I got together a draft and showed it to Gerschenkron."

Shura looked it over and then called Fishlow into the office. "Well," he said. "If you want a degree, I'll give it to you. But I expected something better."

"His sense of disapproval," says Fishlow, "was sufficient for me to throw it away. There I was with two baby girls, going out to take a job in California, and all it took was his saying 'I don't think so' for me to put in two more years on the dissertation. It took me two years to do it over."

Fishlow handed in the revised thesis in 1963. This time Shura was well pleased. "I was truly astonished to see how greatly Fishlow has developed," he purred to Henry Rosovsky. The thesis was put up for and subsequently awarded the David Wells Prize as the outstanding economics dissertation of 1964. The next time Shura saw Fishlow, he invited him to come into the office and sit down. Taking two little glasses off the typing tray, he set them on his desk, opened the bottle of Rémy Martin V.S.O.P., and poured Fishlow a brandy. "Thank you, Professor Gerschenkron," Fishlow said. Shura gave him a subtle look. "Now it is time for you to call me Alex," he said.

Ten years later Fishlow was applying for a new job and needed a letter of recommendation. This time Shura sent off a reference describing "the most brilliant student I have ever had."

|

Gianni Toniolo, Peter McClelland, and Richard Sylla, holding his daughter, Anne, around 1968. |

Courtesy Richard and Edith Sylla |

All the students were subject to these calculated displays of dominance, but Henry Rosovsky was treated to more of them than most. Everything about Gerschenkron intrigued Rosovsky, from the brandy and the lumberjacket [he regularly wore] to more existential matters such as who exactly Shura was. Rosovsky had grown up in the Free City of Danzig (Gdan´sk) speaking Russian and German. He was a Russian Jew, and he was almost sure Gerschenkron was too. "He looked like a Jewish labor leader," Rosovsky says. "And his name was obviously Jewish." Shura considered his religion to be his business, but instead of simply saying so, he preferred to provoke Rosovsky. One year at Passover, Rosovsky announced, "Professor Gerschenkron, I will not be at seminar next week because I have to attend a seder."

Shura fixed Rosovsky with a quizzical expression. "Henry," he said, "tell me. I have always wondered. What is a seder?"

Rosovsky's graduate training at Harvard was interrupted by the Korean War. On the day Rosovsky was called up to Fort Meade, he came to Shura's office to say goodbye. Shura wished Rosovsky well, and then he put a book into his hands saying that this was for Rosovsky to take with him into battle. The book was Sartorius von Waltershausen's Deutsche Wirtschaftsgeschichte (Economic History of Germany). Although he considered it "probably the most absurd book any American soldier ever carried," Rosovsky did keep the Waltershaus-en stuffed in his pack throughout his time in the service, and he found that having it with him in frozen Korea reminded him of life beyond the war.

In 1955 Rosovsky was back in the United States and engaged to his girlfriend Nitza Brown. Rosovsky had considered marriage once before, to a woman named Eliza, but he had broken things off. At the time Rosovsky had suspected that nobody was more disappointed than Shura. Gerschenkron, he knew, had a high regard for marriage. "Henry," Shura told him once, "a nagging wife is a scholar's greatest asset because it keeps him in the library." Shura did not attend Rosovsky's wedding, but a little while afterward a gift arrived at the couple's apartment. They opened the package and found a book of chess problems inscribed with a few Pushkin verses and one line of Gerschenkron: "For quiet matrimonial evenings."

Rosovsky had chosen Japan as his area of specialty "in part, because Gerschenkron knew nothing about Japan." He spent two years in Tokyo, researching a thesis on capital formation in Japan. Every few months Rosovsky sent in a chapter and never once heard anything back. Then Rosovsky mailed in a section which contained a brief discussion of index numbers. Two weeks later he opened his letter box and found a 12-page, single-spaced reply from Shura full of delighted commentary on the Rosovsky use of index numbers.

In 1958 Rosovsky came back to the United States to take a job at Berkeley. There he finished his dissertation and sent it to Massachusetts. After some time had passed, he wrote to Shura asking if he had any information about how his thesis was being received. Did he perhaps know who might be reading it? In the return post came this: "The thesis committee is a secret and curiosity a feminine and hence despicable quality."

Later that same year, the chair in Chinese economic history was created and Shura decided to hire Rosovsky for the position. That Rosovsky was a Japan specialist who knew nothing about China did not trouble Shura. It had long been Shura's contention that Harvard ought always to hire the smartest scholars without much regard to their expertise. Rosovsky could, he pointed out, learn Chinese. Rosovsky thought the idea was ludicrous and said so. Shura did not give up. Back in Berkeley, Rosovsky's telephone rang. Nitza picked it up and reported to her husband that Gerschenkron had two other Harvard professors, Edwin O. Reischauer and John K. Fairbank, on the line for him. Reischauer and Fairbank were the country's two leading Asia specialists, and Shura had persuaded them to assist in the Rosovsky effort. Rosovsky refused to take the call and did not answer the telephone for 10 days. The job was not filled until years later. "One reason I left Harvard and went to Berkeley was that I could not deal with Gerschenkron," Rosovsky says....

In 1965 Rosovsky left Berkeley to take a job teaching economics at Harvard. As members of the same faculty, Rosovsky assumed his relationship with Shura might change a little. In some ways he was right. Now that Rosovsky was a professor, Shura banned him from the seminar. In most other respects things were very much as Rosovsky had left them. When Rosovsky began reading Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's The First Circle he told Shura, and then he made the mistake of allowing Shura to know that he was reading the novel in an English translation. As Shura's voice rose, wanting to know how Rosovsky "could understand the regional dialects of the prisoners if you don't read it in Russian?" Rosovsky achieved a different kind of epiphany. He saw that to Shura "I would always be the student, and he would always be the Master."

Shura's early heart attack in 1958 had taught him that life is short and every hour precious. Convincing young people in their twenties that the end came soon was not easy, and for much of his life Shura searched for a way to do it. Only in 1976 did the ideal means come to him. While having lunch at the Long Table at the Faculty Club, he began to feel poorly. Excusing himself, he walked through the dining room and out into the main foyer, where he collapsed. By the time the firemen from a nearby station arrived on the scene, his heart had not been beating for several minutes. The firemen began thumping on his chest, and eventually they revived him, breaking a couple of his ribs in the process.

Shura's early heart attack in 1958 had taught him that life is short and every hour precious. Convincing young people in their twenties that the end came soon was not easy, and for much of his life Shura searched for a way to do it. Only in 1976 did the ideal means come to him. While having lunch at the Long Table at the Faculty Club, he began to feel poorly. Excusing himself, he walked through the dining room and out into the main foyer, where he collapsed. By the time the firemen from a nearby station arrived on the scene, his heart had not been beating for several minutes. The firemen began thumping on his chest, and eventually they revived him, breaking a couple of his ribs in the process.

...After he was back to teaching, Shura began bringing his students to the Faculty Club foyer. Pointing to a spot on the floor, he would say, "That's where I died." Once he'd let that settle in, he would push his eyeglasses up onto his forehead and continue. "You know, there was nothing. No beautiful colors. No castles. No bright lights. Nothing. So, if there are things you want to say and do, don't wait. Say them and do them. You won't get the opportunity after you're dead."

Many of the students came to think that he tried to make a lesson out of everything he did. Among Shura's commandments was precision. In one of Richard Sylla's papers, Shura thought that Sylla had used a comma where a semicolon was more appropriate. Sylla was not so sure, and triumphantly produced the grammar book that had recommended use of a comma. A day or two later he received a piece of mail from Gerschenkron. Enclosed was an unequivocally pro-semicolon passage copied from Fowler's Modern English Usage, along with a note from Shura that described even Fowler as "much too permissive" and also urged Sylla to "throw away that incompetent book of yours." Sylla ['62, Ph.D. '69, now a professor of financial history at the Stern School of Business at New York University] remembered that "there was a twinkle in his eye the next time I saw him, but it was very serious to him and he wasn't just thinking about my punctuation. He was striving for a Platonic ideal of excellence in everything he did and he wanted us to be the same way."

Shura wanted students who were humble about how much there was to know and yet urgent in their appetite to understand everything. The more specific wish was for his students to be as serious about scholarship as he was. Almost all of them had Albert Fishlow's experience of thinking they had finished their dissertations long before Shura thought they were done. Many of Shura's students became infected by all this intensity, sometimes to extremes. There were students who learned Greek, Latin, and Japanese as members of the seminar. There were students who taught themselves the most advanced new mathematics. There were students who wrote their entire dissertation in Shura's voice, speaking the words aloud in a Gerschenkron accent as they set them down. There were even several students who bought slide rules and began wearing them around every day in their jacket breast pockets, just as Shura did. What D. N. McCloskey ['64, Ph.D. '70, professor of history and economics at the University of Illinois at Chicago] took from this was that "Gerschenkron's theory of teaching was successful at making his students as crazy as he was."

He was inspiring and motivating, and yet there was a painful side. Shura was exhorting his charges to meet ideals which for many of them were unattainable, and when they realized that they could never know as much as he seemed to want them to know, the mutual disappointment could be profound....

"His interaction with his students did something for him emotionally," says [Paul] David. "I had the feeling I was being manipulated. There are lots of powerful models who do that. For me, it pushed me in the opposite direction. But I so admired him that I never quite got into a state of outrage."

As David thought about it, he decided that Shura was paternal with his male students in a way that was "characteristic of the awkwardness between fathers and sons in societies with strong patriarchal traditions. I think it was the sense that relations with him were very complex and charged with the sorts of ambivalences that often complicate families." Shura treated economic history as the family business that he wanted the students to take over for him. He cultivated the students warily and uneasily, hoping that they would bring him honor, and yet always looking to outdo them himself.

Yet that wasn't all of it. Shura was also a lot like the masters from the old British and American schoolboy novels he liked so well, Tom Brown's School Days, The Willoughby Captains, and The Lawrenceville Stories—ferocious men with the souls of kittens. Shura liked to tell his sister Lydia how much "heart and brains" his students had. "He was so proud of them," she says. And when a professor at Yale asked him to evaluate the virtues of his students for a possible job offer, he did his best and then gave up, explaining, "Who can presume to compare the creatures of the Lord?" Beyond the stern veneer, Shura was really on their side all along. They were all his boys. In his old age he even told one of them so. When Peter McClelland finally left Harvard for Cornell, Shura wrote him a letter. "Dear Peter," he said. "The school year has started, and it makes me wistful after all those years....I do miss you."

Shura's theory of backwardness made him famous, but his most glorious legacy is pro-bably his students. "As I get older," says D.N. McCloskey, "more and more of my life is a scholarly imitation of his." They are all like that in some way or another, right down to the bottle of Rémy Martin V.S.O.P. cognac Henry Rosovsky keeps in his lower right desk drawer. Most of them would agree with Gianni Toniolo [now professor of economic history at the University of Rome "Tor Vergata" and at Duke], who says that after he came to the United States from Italy just so he could study under Shura, "he changed my life." When he left Rome, Toniolo had his degree and a generous job offer from the Bank of Italy that he'd nearly accepted. "But I decided that being an intellectual would be more fulfilling, and, to this day, I still wonder every month when my check comes why I'm being paid to do this because I'm so very happy."

Nicholas Dawidoff is the author of The Catcher Was a Spy: The Mysterious Life of Moe Berg and editor of the Library of America volume Baseball: A Literary Anthology, published this spring.

From the book The Fly Swatter, by Nicholas Dawidoff. Copyright 2002 by Nicholas Dawidoff. Published by arrangement with Pantheon Books, a division of Random House Inc.