Jersey barriers (which the New Jersey Highway Department introduced in 1955), ring the Washington Monument and block off Pennsylvania Avenue in front of the White House. Bollards, the concrete pots and metal posts designed to stop trucks, surround corporate headquarters and public sites like Times Square. With no sign that the threat of attack has abated, design professionals say, nevertheless, that the new emphasis on building security poses a danger of its own: subverting important aspects of public space.

|

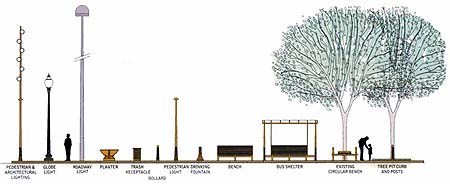

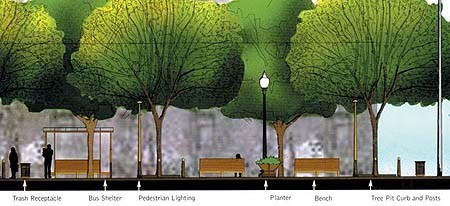

| Hide in plain sight: proposed "hardened" streetscape elements for Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C. (left), and a streetscape rendering (below). [view larger image] |

|

| [view larger image] |

| Drawings courtesy of Martin Zogran |

Intrusive, highly visible structures like Jersey barriers may actually foster more worries than they prevent, heightening fears that there is something to be afraid of. In response, Alex Krieger, M.C.U. '77, professor in practice of urban design, is at the forefront of a movement that hopes to both preserve and enhance the public realm while "hardening" potential targets by making them more impervious to attack. In March, a two-day conference at the Graduate School of Design (GSD) on "Designing Streetscapes and Landscapes for Security" brought together design and security professionals to discuss the new threats they must now consider.

Krieger's architectural firm, Chan Krieger and Associates Inc., served as the coordinating architect for a study by the federal government's National Capitol Planning Commission (NCPC) on how best to redesign Washington, D.C., to meet security needs. A 100-page report, released at the end of 2002, is now working its way through various oversight commissions. It provides radical solutions that Krieger hopes will make the nation's capital both a more welcoming place for visitors and a more di±cult target for terrorists. "This project was meant to make security less off-putting, less conspicuous," says Krieger, who also chairs the GSD's urban planning and design department.

Although the NCPC project examined some Star Wars-like technologiessuch as invisible force fields around potential targets, or "smart roads" that would sense the approach of an explosive-laden vehicle and deploy barriersthe final report suggested ways to hide security measures in plain sight. The design review suggests replacing the loose configuration of dirt-filled concrete planters and Jersey barriers with "hardened" versions of regular street objects.

"You deputize the normal accoutrements and incorporate those into your security design," Krieger explains. By building street benches, lampposts, trashcans, or even parking meters and drinking fountains to more rigorous specifications and then anchoring them deeper in the ground, designers could provide protection while maintaining the historic grandeur of famous boulevards like Pennsylvania Avenue. The result is a streetscape that protects against car bombs yet allows pedestrians to move through it without a sense of unease.

The large-scale rethinking of Washington's physical security exemplifies one of the most pressing issues facing secure-design professionals: how to safeguard conspicuous buildings in urban settings where other structures may not need such measures. Tougher versions of everyday objects would allow hardened and unhardened buildings to intermingle: a hardened street bench in front of a police station would look the same as one in front of a restaurant down the street. Depending on the level of security necessary, architects can also harden buildings themselves, using a variety of techniques. Increasing a building's set-back from a road, for example, can lessen the damage from an explosion, and plastic glazing on windowslike that used to secure the Pentagoncan prevent shattering.

In some cases, Krieger and his colleague Martin Zogran, M.A.U '99a design critic in urban planning and design at the GSD and an architect at Chan Kriegersay that they see security hardening becoming a "badge of honor," that organizations are linking their importance to the need for extensive building security: the more extensive the security, the more critical the work done inside.

This drives many private companies to move ahead with security measures on an ad hoc basis. "Conspicuous buildings that perceive themselves as targets are moving a lot faster than the government," Krieger observes. Concrete planters now surround the Reuters Building in Times Square, for example, and bollards are being erected around the Hancock Tower in Boston. Such haphazard security designs can severely damage the sense of space around a building or along a city block.

Ever since September 11, Krieger reports, his firm has encountered a new interest in security for a wide range of architectural settings: recently, a group of investors sought a security review for a retirement community. He expects that physical-security reviews will soon be routine. "It's going to be another layer of investigation that any building project is going to undergojust like air conditioning, heating, or engineering," Zogran adds. "Now there'll be a security component, too."

~Garrett M. Graff

Alex Krieger e-mail address: akrieger@gsd.harvard.edu

NCPC report website: www.ncpc.gov/publications/udsp/Final%20UDSP.pdf