Having hired a team of consultants and engineers one year ago to assess the University's existing real estate assets in Allston, as well as the infrastructure needs of a future campus across the river, Harvard's leaders are taking a deep breath before making any decisions. Among considerations that will figure into any plan, says chief University planner and director of the Allston Initiative Kathy Spiegelman, are four main questions: What are Harvard's academic program requirements? What does the real estate allow in terms of physical planning? What does the political process allow? What is the cost? The first and last questions are proving to be the most challenging.

As a first step toward figuring out future program requirements, the School of Public Health, the Graduate School of Education, the Law School, and the Kennedy School of Government have each completed studies of what they might do in Allston as compared to their current locations. But the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS), with an immediate need for science facilities for existing faculty, is actively pursuing expansion in Cambridge on a site east of Oxford Street.

Last year, four advisory groups, composed primarily of faculty members, developed scenarios emphasizing different uses of Harvard's Allston land. One looked at graduate and professional education, contemplating the feasibility of creating an academic precinct across the Charles River. Another studied the pros and cons of building new cultural amenitiesmuseums, theaters, or performance spaces. The third looked at housing, primarily with an eye to addressing the needs of graduate students. The fourth, the science committee, had perhaps the most challenging task. Neither FAS nor the Medical School, the two major centers for Harvard's science programs, has immediate needs for Allston space, unlike some schools and other parts of the University. Yet for science in Allston to be feasible virtually requires their participation. Add to that the burgeoning interdepartmental nature of fields like bioengineeringwhose heavy computational needs intersect with requirements for traditional "wet lab" spaceas well as possibilities for intra- and inter-institutional collaborations (see "Genomic Joint Venture"), and the patterns of future growth become highly unpredictable. "Science has been the most difficult to plan," says Spiegelman, "because it is so dynamic."

|

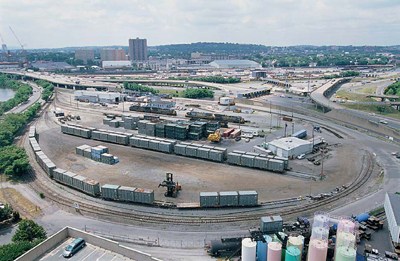

| Harvard, while continuing to acquire more property in Allston, like the Beacon railyards, is carefully weighing the alternatives for its new cross-Charles acreage before proceeding with further planning. |

| Photograph by Jim Harrison |

Even as the question of what will emerge in Allston becomes more complex, the University's holdings across the river continue to grow. Most recently, the University acquired commercial property housing the headquarters for Bickford's Family Restaurants; Harvard has also been approached by the board of the Charlesview Apartments, an affordable housing development at the intersection of Western Avenue and North Harvard Street, to discuss whether there is any University interest in their land, says Spiegelman. "That might be the source of a better future for them than trying to maintain the buildings that they already have." The Charlesview board is keeping the tenants informed and has hired a consultant to ensure that whatever Harvard might offer or suggest will be in the residents' best interest.

Regardless of what properties Harvard eventually owns in Allston, development will track the transportation possibilities, says Spiegelman. That is why the recent acquisition of 91 acres of putatively undevelopable land from the Massachusetts Turnpike Authority (MTA) could in the long term be advantageous to Harvard and the North Allston community (see "Over 91-Acre Allston Purchase, a Fresh Political Maelstrom," July-August, page 67). A $1-million transportation study (paid for by the University, but conducted by state transportation secretary Daniel A. Grabauskas) will examine a host of issues, including railyard-to-port connections; reconfiguration of the turnpike off-ramp and the rail tracks across two Harvard parcels that were formerly owned by the MTA; strategies for calming traffic on Storrow Drive (a major barrier between Allston and the river); and the possibility that a long-discussed "urban ring" public-transit system might link to North Allston.

Indeed, one of the most important conclusions of the academic planning this year was the recognition that Harvard Square, North Allston, and the Longwood Medical Area must be better connected. Allston is not very well served at the moment, says Spiegelman. The Larz Anderson Bridge is congested and there is no good public transit access.

The consultants Harvard hired last year were supposed to figure out how much it would cost to address those infrastructure challenges. But Harvard administrators are not ready to share those big numbers yet, pointing out that until the time-frame for development of Allston is knownwhether over 15, 30, or 45 yearsthe annualized expenditures can't be determined and so put into perspective.

An understanding of the financial and economic consequences of how Allston is developed is still at an early stage. "We are dealing with a very important set of choices," says Jacqueline O' Neill, Allston Initiative communications and external-relations director. "President Summers wants to make sure he gets them right, because they are a very long-term, consequential set of decisions." The challenge, says Spiegelman, is to think about what will move a very complicated agenda that has to do with the pursuit of knowledge far into the future. "The consultants have given us lots of information that will help President Summers and the Corporation make the decisions that will capture the essence of what Harvard will be 50 years from now. Only they, not our consultants, can tell us that."