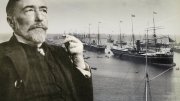

Many call Rudyard Kipling the scribe of the British Empire, but novelist Joseph Conrad (1857-1924) may have best rendered its waning years and foreshadowed its demise. Around the turn of the last century, Conrad’s books portrayed terrorism in Europe, limned the reach of multinational corporations, and foresaw patterns of globalization that became clear only a hundred years later. The contemporary Colombian novelist Juan Gabriel Vásquez has described Conrad’s books “as ‘crystal balls in which he sees the twentieth century,’” says professor of history Maya Jasanoff. “Conrad observed the world around him from distinctive and diverse vantage points because of his own cosmopolitan and well-traveled background,” she continues. “Henry James wrote him a letter that said, ‘No-one has known—for intellectual use—the things you know, and you have, as the artist of the whole matter, an authority that no one has approached.’ James meant not only what Conrad had seen, but the depth of his insights. I would echo that.”

Born in Poland, Conrad spent 20 years of his adulthood as a merchant seaman on French, Belgian, and English ships, steaming to Africa, the Far East, and the Caribbean before settling down as an author in England. His grasp of the tensions and forces tearing apart the Victorian-Edwardian world is a counterweight, says Jasanoff, to the “widely held stereotype of the period as a golden age before everything got wrecked in the trenches of World War I. If you read what people were actually saying then, you get a strong sense of social and economic upheaval. World War I didn’t come out of a vacuum. Conrad’s novels suggest what it was like to be a person living in those times. Fiction can bring alive the subjective experience of the moment, which isn’t rendered by the kinds of documents historians usually look at.” “World War I didn’t come out of a vacuum.…Fiction can bring alive the subjective experience of the moment, which isn’t rendered by the kinds of documents historians usually look at.”

Jasanoff is writing a book, tentatively titled “The Worlds of Joseph Conrad,” that focuses on four of his novels: Lord Jim, Heart of Darkness, Nostromo, and The Secret Agent. The backdrop to Lord Jim (1900) is the era’s international and intercultural maritime life. Heart of Darkness (1899) probes the fallout of colonial empires, and adumbrates their demise. Nostromo (1904) explores political instability, dictatorship, and revolutionaries in Latin America, with a treasure in precious metal at the center of the story. The Secret Agent (1907) delves into anarchism, agents provocateurs, and a terrorist bombing—purportedly a symbolic attack on science—at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich.

Unsurprisingly, ships, rivers, and oceans figure importantly in most of these books. But unlike the vessels of Herman Melville, Conrad’s ships include steam-powered ones. He writes, Jasanoff says, about the “industrialization of the sea.” Steamships shrugged off the vagaries of wind and water far better than sailboats. They also enabled cheaper, larger-scale intercontinental migrations, like those of so many Europeans to the United States: Lord Jim opens with a shipload of Muslim pilgrims making the hajj from southeast Asia to Mecca. New technologies of transportation and communication, like the telegraph, were transforming international demographics and patterns of commerce: improvements in refrigeration enabled Europeans to eat meat from Australia and New Zealand, for example. All these changes affected Conrad’s fiction. Nostromo’s title character is an Italian expatriate in Latin America; a local silver miner of English descent also figures in the plot. Conrad eventually captained a cargo ship in the Indian Ocean, and had to make telling decisions like how much wheat from Australia or sugar from Mauritius to load onboard.

“I want to restore shippers, shipping agents, sailors, and dockworkers to our picture of how globalization actually worked,” Jasanoff says. To get a full sense of shipping life on some of the oceans Conrad knew, she booked herself as the sole passenger on a container ship last December, making a month-long voyage from Hong Kong to Southampton, England, and posting a blog about her experiences. “On the boat, there is an incredible contrast between the enclosed container boxes and being out in the middle of the ocean,” she says. “When I got off the ship, I was struck by how closed-in I felt everywhere: there were buildings, trees, and things getting between me and the light. That tension between freedom and constraint is a defining element of being on a boat. After spending 20 years of his adult life around ships, it’s hard to imagine it didn’t influence Conrad’s understanding of the parameters of human action.”

Jasanoff makes imaginative use of atypical sources in her research. For example, Edge of Empire: Conquest and Collecting in the East, 1750-1850 (2005), her award-winning first book, illuminated the British empire by examining individual collectors of art objects and material culture in colonial settings. Liberty’s Exiles: American Loyalists in the Revolutionary World (2011) painted the diaspora and fate of thousands of Tories after their side lost the Revolutionary War; it won the National Book Critics Circle Award for nonfiction.

Literary studies, such as the well-established school of New Historicism, often seek to locate literature in historical contexts. Yet the converse doesn’t, so far, apply. “Historians remain pretty wary about the use of literature,” Jasanoff explains. “Those working on earlier eras, where there’s less available, often engage more with literary materials. For the modern period, where we have such a plethora of written materials and other documents to draw on, we tend not to make literature the centerpiece.” Jasanoff, who concentrated in history and literature at Harvard, graduating in 1996, may be perfectly positioned to rectify that imbalance—with help from Joseph Conrad.