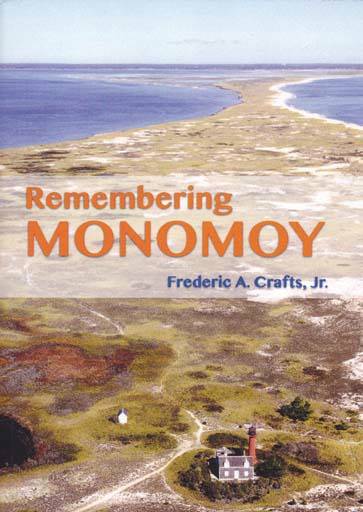

Fred Crafts ’50 was six when in 1935 his father first took him hunting on Monomoy, which juts into Nantucket Sound “at the elbow of Cape Cod some 70 miles southeast of Boston,” as he puts it in the introduction to his first book, Remembering Monomoy. The sometime island(s), sometime peninsula, now a National Wildlife Refuge, “has been my second life,” he writes, and the future lawyer, land planner, and developer began collecting information about the spot in 1950.

In 2012, staff members at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service headquarters in Chatham, Massachusetts, asked him, as the last surviving hunting-camp owner on Monomoy, to share his recollections. That “simple request turned into a very enjoyable project”: his 230-page omnium-gatherum contains personal reminiscences and photographs; copious reprints or summaries of related newspaper and magazine articles; copies of relevant maps, charts, and official documents; reproductions of duck stamps from 1939 to 1971; and even a 15-page memoir of Monomoy Point “circa 1900” written in the 1980s by another one-time resident. Besides fishing, hunting, and camp life, Crafts covers the Coast Guard on Monomoy and tells how, geologically and historically, the wildlife refuge came to be, recalling now-vanished places like Wildcat Swamp, a songbird haven with abundant high bush blueberries, “the healthiest and...best flavor I have tasted.”

Crafts’s father, Judge Frederic A. Crafts Sr., went duck hunting on Monomoy with state game wardens in 1934. He liked it so much he bought a three-room “camp” there (adding his son’s name to the deed), where his family spent almost every weekend, from April to December, until 1950. By then, terrain and use were both altering. Approval for Monomoy’s “taking” for public use was given by all federal and state agencies in 1940. The judge “worshipped” Teddy Roosevelt, his son recalls, and as “a conservationist as well as a duck hunter, he realized there was a crying need for a wildlife refuge,” but he also negotiated life tenancy for existing camp owners on the then peninsula.

When the author’s children were growing up, in the 1960s, beach buggy access to Monomoy had ended. The family rented a cottage for a few weeks each summer and visited what was once again an island by small boat during their stay; later, he supervised annual Boy Scout camping trips to Monomoy until 1987. But “Mother Nature pretty much does what she wants to,” he writes; in 1991, he let Fish and Wildlife burn the remains of his vandalized, much-eroded camp.

Crafts is happy his self-published first printing of 500 copies is running out, and his book is going back to press (for information, contact facraftsjr@gmail.com). His goal “was to collect as much information as possible about all aspects of Monomoy, past, present, and future...[in] one book so readers could better understand what is going on, as nothing stays the same on Monomoy or the outer Cape barrier beaches.” Wetlands preservation, he stresses, should be a primary concern: “They are the source of life for so many different species. You see this if you’re a duck hunter, sitting in the marsh all day.”