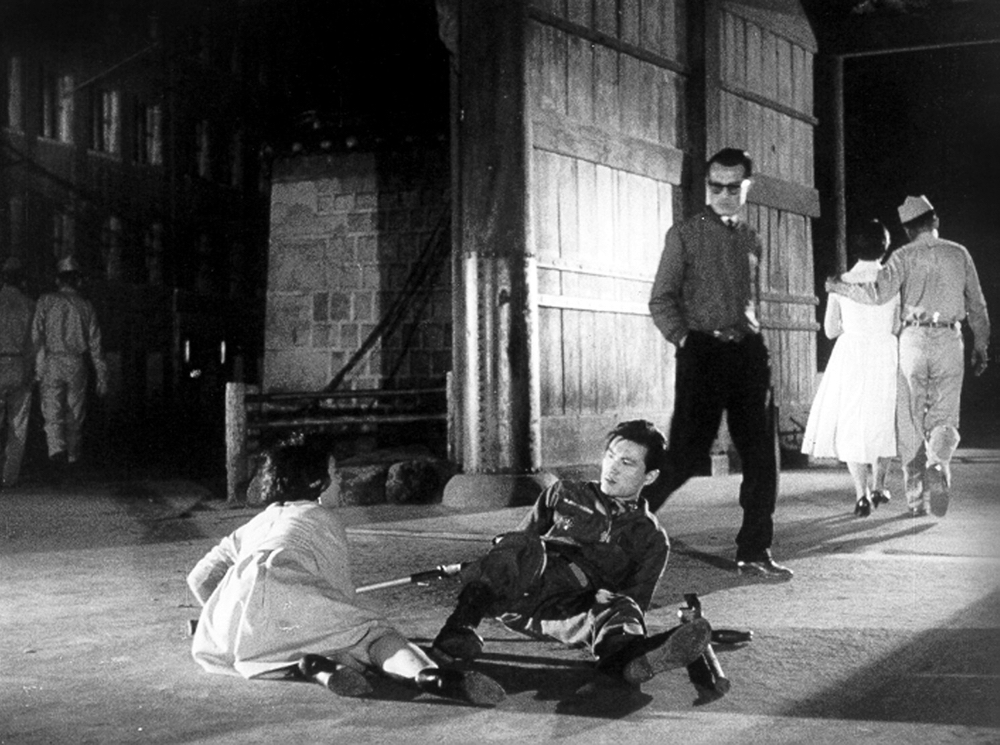

In the middle of Shin Sang-ok’s 1958 film The Flower in Hell, a Korean woman dances for a group of American soldiers on a U.S. Army base in Seoul. Behind her, a band plays a cheery mambo. The camera seems to adopt the gaze of the soldiers, panning down the woman’s body, lingering on her legs. The dance lasts for three minutes, almost uncomfortably long—but the viewer has no choice but to keep looking. Interspersed with the dance scene is an attempted robbery of American army supplies by a group of Korean men who live near the base.

The sequence is an amalgam of styles: the footage from the army base is likely documentary, reminiscent of an Italian neorealist approach; the heist attempt recalls American crime films. The point of view is also inconsistent—if the viewer shares the soldiers’ perspective during the dance, through whose eyes are we viewing the theft?

October 1, 2023, marked 70 years since the signing of the U.S.-South Korea mutual defense treaty. A film series running at the Harvard Film Archive (HFA), “Out of the Ashes—The US-ROK Alliance & South Korean Cinema,” uses the anniversary as an opportunity to explore the contradictions and fissures of South Korean society in the years during and after the war. Many of the films, like The Flower in Hell, are marked by an instability of genre and perspective: destabilizing features tied to larger ambivalences about the American presence in South Korea and the country’s rapid modernization in the postwar years. HFA director Haden Guest and postdoctoral fellow in East Asian languages and civilizations Chan Yong Bu collaborated to curate the series, which began on November 3 and will run through December 3.

Pegging the series to the anniversary of the defense treaty may at first appear to highlight South Korea’s subordination to the United States during the postwar period, when the country became a key outpost in the U.S.-led Cold War bloc in Asia. But the 1950s were a time of relative freedom in Korean cinema, Bu says—an era when films like The Flower in Hell could, at least obliquely, critique the American military and cultural presence in the country. “In the 1950s, although there was absolutely censorship against pro-communist narratives or pro-North Korea narratives, we also need to remember that it was right after the Korean War, so the government didn’t have the luxury of censoring everything,” Bu says. “There were much larger things going on.”

In The Flower in Hell, Dong-shik, a young man from the countryside, comes to Seoul in search of his brother Yeong-shik. Dong-shik finds that the city—supposed to be a beacon of modernity and progress—is destitute, rife with crime and buckling under the pressure of a large American military presence. Eventually, Dong-shik finds Yeong-shik and meets his brother’s girlfriend, a sex worker named Sonya who services American soldiers.

Though Dong-shik tries to convince his brother to return to the country with him, Yeong-shik refuses, drawn to Sonya for all that she represents: prosperity (“What are we going to do with all this money?” one sex worker asks) and Americanization (Sonya, like the other sex workers in the film, is referred to only by her English name). Dong-shik, too, is allured by Sonya and her promises of wealth and modernity—but soon finds these promises empty. He rejects the course of progress—toward the city, toward industrialization, toward American culture—that his brother has tried to take and returns home to the countryside.

In this and other movies in the series, fans of contemporary Korean dramas and movies will find familiar narrative and character tropes. Like The Flower in Hell, many modern Korean dramas and movies are characterized by a dichotomy between the country and the city, and a deep ambivalence about rapid economic progress—especially in light of the extreme inequality it leaves in its wake (think of Parasite and Squid Game). Sonya, too, is an early example of a popular trope—what Bu terms the “Americanized Korean woman,” whose downfall is shaped by her blind desire for the riches of America and her spurning of traditional values.

Screening these films as part of a series provides an opportunity to notice the similarities and differences in how these motifs are used. In Lee Yong-min’s Holiday in Seoul (1956)—also screened early in the series—an upper-middle-class husband and wife find their day off from work derailed by various unexpected crises. Like The Flower in Hell, the film is characterized by a disjointedness: the misadventures of the husband and wife fit together like pieces from different puzzles. One moment, the husband, a journalist, is chasing a suspected killer; the next, he’s caring for a neighbor’s daughter. Meanwhile, the wife—an obstetrician—goes from helping a young woman who’s gotten pregnant out of wedlock to having drinks with her husband’s colleagues.

But Holiday in Seoul differs from The Flower in Hell in its treatment of the character of the wife, Hi-won. Like Sonya, Hi-won is a symbol of westernization. She works as a doctor, even as other characters scoff at a woman working outside of the home; she gazes longingly at English-language ads; while other women don traditional Korean clothing, she wears Western-style dresses. But her Americanization does not lead to her downfall: rather, Hi-won serves as the moral heart of the film, when at the end she insists that her husband not interview a woman who has just had a difficult birth so that she can have time to recover.

Guest says that the movies do not need to be watched in any particular order: “The series is meant to allow entry at any time,” he says. “Even for those who can only see one film, each film stands on its own merits.” If the curators had to recommend one remaining movie from the series, it might be Yu Hyun-mok’s Aimless Bullet (1960), which will be screened on December 3 and is considered by many to be one of the best Korean movies of all time.

And for viewers who want to see the movies that have already been screened, the Korean Film Archive has made almost all of them publicly available on its YouTube channel—though Guest encourages those who can make it to the remaining screenings to do so. “These movies were made to be seen on the big screen,” he says, “and it’s a very rare opportunity to see them in that way.”