In a severely polarized country, Americans’ political mindset is increasingly shaped by “zero-sum” views of policy and society: the belief that gains achieved by one individual or group come at the expense of another. If the resources available are fixed in supply, when one interest gains a larger slice of the “pie,” that necessarily leaves a smaller share for everyone else. The zero-sum mentality is a formula for intense division, as rival interests influence debates on issues ranging from immigration or taxation to race- and gender-based affirmative action.

Ropes professor of political economy Stefanie Stantcheva founded Harvard’s Social Economics lab, where researchers are studying this type of thinking. The research goes beyond polling instruments, which only get at respondents’ surface opinions. Through large-scale socioeconomic surveys, data analytics, and big data tools, Stantcheva and colleagues identify patterns that help explain how beliefs are shaped by experiences, demographics, and even generational histories.

“These are not just your regular opinion surveys or polls,” Stantcheva says. “Instead, they’re deep research dives into how people reason. We do this at scale, using very large samples.” The lab’s work reveals a striking finding: zero-sum thinking exists on both sides of the ideological divide. Although the respondents’ zero-sum frame manifests differently depending on the issue, it always affects their political discourse and policy positions. “When we think about Republicans versus Democrats,” she says, “it is not the case that one group is systematically more zero-sum.”

Consider views on immigration. Zero-sum thinking is often linked to lower support for immigration in the United States. If you tend to be more zero-sum in thought, Stantcheva says, “you may think that the gains of immigrants come at the expense of non-immigrants,” where the integration of new groups into society is seen as draining resources from existing citizens—leading to “nativism,” or the desire to protect the interests of native-born inhabitants against immigrants. As national dialogue has deeply reflected, Pew Research Center data from June 2024 reveals stark contrasts between supporters of President Donald Trump and former President Joe Biden:

-Trump supporters: Approximately 63 percent favor national deportation efforts for undocumented immigrants, and 41 percent oppose any legal stay for them.

-Biden supporters: About 85 percent support legal avenues for undocumented immigrants, with 56 percent advocating for citizenship pathways.

Much of this divide was shaped by rhetoric around job availability and concerns that immigrants might replace U.S.-born workers, reflecting a zero-sum mindset. Notably, some Latino men shifted toward Trump in the November election, with Edison Research exit polls showing Trump secured 54 percent of the Latino male vote. Many Latino voters, particularly in areas with large Latino populations, may have thought stricter immigration policies would reduce competition in the labor market. Trump’s emphasis on limiting illegal immigration and strengthening border security was often framed as a measure to protect American jobs, which likely resonated with those concerned about economic opportunity. While Trump appealed to right-leaning voters with zero-sum thinking on immigration in the 2024 election, this mindset also appeared among left-leaning voters, especially working-class and blue-collar Democrats. In fact, Stantcheva argues that zero-sum thinking can help explain variations in policy views within parties—Democrats who hold more zero-sum views tend to be more strongly opposed to immigration. For example, in 2024, Democrats in swing states, particularly those from industrial sectors, expressed concerns that immigration strained public resources and increased job competition.

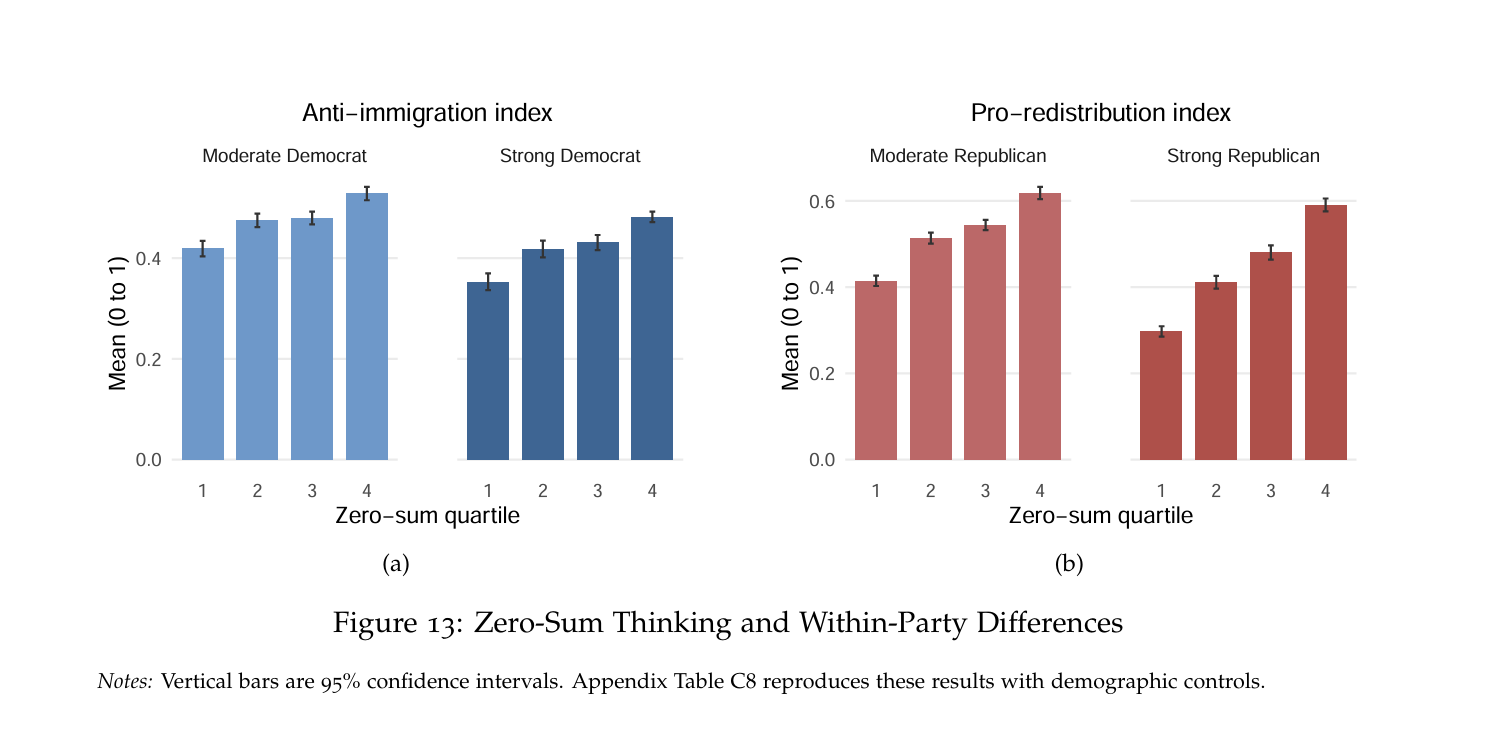

Shown are the links between the anti-immigration index and zero-sum thinking among Democrats (in Panel A) and the pro-redistribution index and zero-sum thinking among Republicans (Panel B). Democrats who hold a more zero-sum view are more concerned about immigration and are more strongly opposed to increased immigration. Similarly, within the Republican Party, the most zero-sum individuals are more likely to support redistribution. From “Zero-Sum Thinking and the Roots of U.S. Political Divides,” May 15, 2024, by Sahil Chinoy, Nathan Nunn, Sandra Sequeira, and Stefanie Stantcheva.

How is zero-sum thinking spread across different populations in the United States? “In general, people who live in urban areas and in big cities are much more zero-sum than people who live in rural areas,” Stantcheva explains. “For instance, in the U.S., one of the least zero-sum states is actually Utah,” she reports, “followed by Hawaii, and the most zero-sum state is New York.” Zero-sum thinking thrives in environments where competition for limited resources is perceived as intense—something more common in urban areas like Manhattan. In cities, resources such as housing, jobs, and public services tend to be more concentrated and competitive. As cities experience higher population density, residents may perceive these resources as limited and thus see newcomers or immigrants as direct competitors.

In contrast, rural areas typically have more space, lower population density, and less competition for economic resources, leading to less of a perception that immigrants or new residents are “taking” resources away from native citizens. On the flip side, urban diversity can soften these perceptions, as residents are more likely to benefit from the cultural and economic contributions of newcomers. In rural areas, more homogenous populations tend to foster stronger in-group dynamics, which can amplify zero-sum thinking (for more on the psychology of group behavior and social antagonism, read “The Gravity of Groups,” May-June 2024).

Zero-sum thinking varies by state and region generally, and Stantcheva says historical factors also play a role: “Counties in the U.S. that historically had high rates of slavery still exhibit stronger zero-sum tendencies today.” Migration patterns from the American South, where such historical baggage is entrenched, may have spread this mindset to other parts of the country. “There was a migration, for instance, of white southern migrants from the South to other places [in] the country,” Stantcheva says, “And they seem to have taken this culture with them.” Regions like the Midwest, which have higher shares of these migrants, are more likely to exhibit a zero-sum mindset. In general, people with ancestral ties to oppression, discrimination, or enslavement tend to hold more zero-sum views—including on both sides of the equation, oppressed and oppressor. “This extends beyond the enslavement prevalent throughout the South,” Stantcheva says, “to other forms of enslavement—such as the Holocaust or forced reservations for Indigenous populations.”

A major objective of Stantcheva’s research is relating today’s zero-sum thinking to individual or group histories. “We asked people about a whole range of experiences by their parents, their grandparents, related to the history of their family. And we can see that these personal and family experiences really seem to affect your mindsets,” she says. “For instance, we find that if you grew up during a time with higher economic growth and higher economic mobility, you’re less likely to think in zero-sum terms today. If your family experienced upward mobility, you're much less likely to think in zero-sum terms.” In fact, the phenomenon appears in the United States as a generational divide—a cohort effect resulting from the economic climate individuals were raised in.

Economic growth began to slow in the United States beginning in mid-1970s and especially with the Great Recession from 2007-2009, resulting in declining shares of U.S. household income held by the lower and middle classes—patterns which have continued to impose stark differences between the mindsets of baby-boomers and Generation X-Generation Z. “The younger generations in the U.S. grew up [during] times with less growth and less mobility,” Stantcheva says. “And so, they have a much more zero-sum mindset than the older generations, [who] grew up at times with faster growth and much more mobility,” (notably the unprecedented American economic growth following World War II, when baby boomers were growing up).

Indeed, across the political spectrum, “people who have lower incomes in general tend to be somewhat more zero-sum than people with higher incomes. People with lower education levels are somewhat more zero-sum than those with higher education levels.” However, at the top of the education distribution, the pattern shifts. At the level of advanced degrees, like Ph.D.s or professional degrees, the data show an uptick in zero-sum mindedness—this shift may be attributed to the heightened competition involved in gaining admission to, and succeeding in, advanced degree programs, where the demands for performance and achievement can be intense.

When individuals across the political spectrum view society as a zero-sum game, and their political representation is closely divided, their perception of policy responses and the actions they choose to support are increasingly shaped by that underlying worldview. In the current political moment, it is difficult even to imagine a society in which the pie of goods and resources itself is made bigger, and the political tensions and temperatures might be dialed down.