’Tis the season to celebrate New England makers. The plethora of products designed and manufactured throughout the region offer something for everyone, and for every budget. “How we spend our money is a reflection of our values,” notes Deb Dormody, an alumni and family relations officer at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). “Supporting independent artists and makers is a way of demonstrating what you believe and helps the local economy.”

As a gateway, she points to RISDmade, an online site featuring 400 alumni makers from across the globe, many of them based in New England. Artist biographies, along with examples of what they create and how, “help educate the consumer about what really goes into making each piece of art,” Dormody says, ranging from ceramics, light fixtures, and cookware to jewelry and scarves.

Among the designers is Colin Sullivan-Stevens, founder of the Portland, Maine, company Anchorpak. The stylish line of durable, ergonomic bags features design elements, such as a balanced strap loop and a closed pouch, that mitigate pressure on the wearer’s back and shoulders. This makes the bags ideal for bicyclists, hikers, tourists, or parents juggling kids, strollers, and snacks. For high-quality, beautiful cast-iron cookware, check out Nest Homeware, owned by Matt Cavallaro. From braising pans and skillets to Dutch ovens, the smooth-surfaced vessels are cast and machined in Indiana and finished and seasoned in Providence—and are crafted to last forever. In nearby Cranston, Rhode Island, Matthew Hall Originals sells tasteful metal-based housewares in refined organic shapes: baby horseshoe crab or lobster claw key chains, quahog shell bottle openers, and turtle-shell belt buckles.

| Photograph courtesy of Matthew Hall Originals

In Western Massachusetts, ceramicist Cara Taylor makes minimalist, sculptural porcelain pieces that serve a purpose: vases, candlesticks, salt and pepper shakers. More recently inspired by basketry, she also has a line of “woven vessels.” “I love flowers and food and interior design,” she says. “I’ve always been fascinated by containers and thinking about what’s going to look good on the table.” Objects are formed with thinly rolled slabs of clay, a process that also yields scraps. “My favorite part is when I get some weird shapes left over and those become the basis for my one-of-a-kind pieces and I get to play around,” she says. “It’s almost like there’s a puzzle and the answer’s in me, somewhere.” (Her Easthampton, Mass., studio, Taylor Ceramics, is also open to visitors on December 6, 7, and 13 as part of the Cottage Street Open Studios event.)

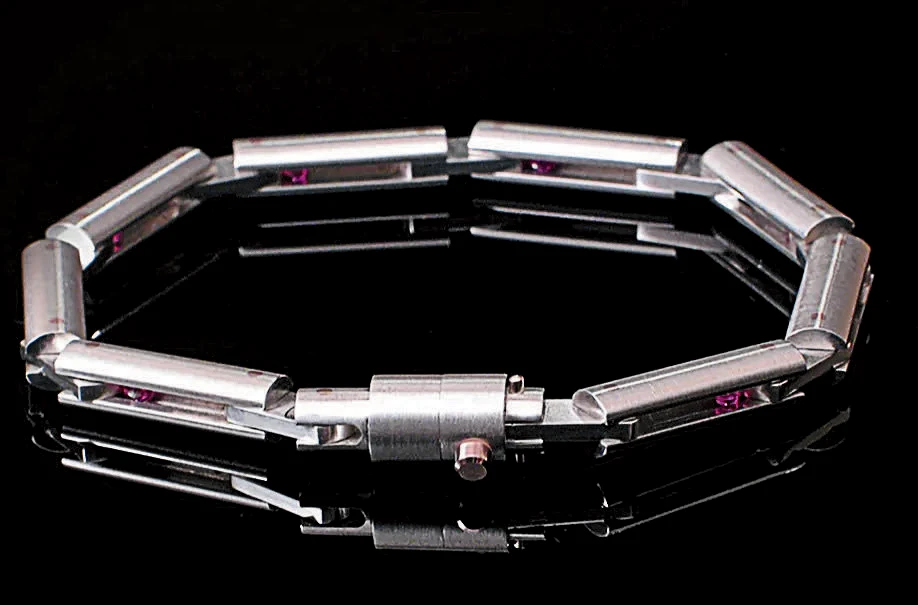

For unique jewelry, try the Matthew Feldman Gallery in Cambridge. He opened the Huron Village storefront in 2000 and sells his own work and that of other artists, including three in New England: Rob Greene, Judith Kaufman, and Vicki Eisenfeld. Feldman’s engineering style, something akin to constructing precision instruments, defies easy description. He often uses titanium, stainless steel, and a DuPont product called Delrin (a high-performance, semi-crystalline thermoplastic) that’s typically reserved for manufacturing gears and bearings. “Trying to mix up the context for what people are used to seeing in certain objects, I find, is not a bad thing. These materials are industrial,” he says, “because they are super functional, right?” One titanium ring on display features tiny ruby balls with “a sphericity within three-millionths of an inch,” he adds, that are “mostly used in precision instruments like watches and gauges.” Originally a leather artist, Feldman’s gallery also displays some of his exquisite fine-grained black handbags (one of these can be found in the Museum of Fine Arts’ collection). “It’s possible to feature aesthetic value,” he says, “without sacrificing function.”

Speaking of precision, every knife that leaves the Lamson Products factory in Western Massachusetts passes “the paper test,” says production manager George Yacoub. That means that after the Vintage-series blades are laser-cut and ground and the handles applied and hand-finished, a master sharpener, like Dan Hale, who has been with the company since the late 1980s, hones the blade. When done, he holds a piece of paper in the air and slices it in half with the new knife. Any catch and the blade is re-sharpened. “As a knife manufacturer,” says Yacoub, “the most embarrassing thing you can possibly have is sending out a knife that’s dull.”

The company is based in Westfield (with a factory store in Shelburne Falls) and was founded in 1837 as Lamson & Goodnow, banking on the success of American Silas Lamson’s invention, the scythe handle. The company went on to produce knives, cutlery, and other kitchen tools and now offers seven different lines of knives, including the Vintage series, which is laser-cut from American steel in Shelburne Falls, and the connoisseur-oriented Forged line, made locally from top-quality German steel. “It’s not a machine that’s making that handle feel good for you, it’s the right person, and that’s a hard job. They are artists out there,” Yacoub says, gesturing across the factory floor. “Every single piece is touched by people right here.” Among the most popular gifts are the chef, utility, and paring knives, which come in various handle finishes—the “fire” line is a glittery, marbled red acrylic handle—but the eight-inch forged Chinese santoku cleaver with a walnut handle is also a pleasure to chop with.

In thinking about how communities can support creative cultures, it partly comes down to caring enough to make the effort. Cara Taylor remembers that, during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, people came to the open studio saying they were only buying gifts available within a 10-mile radius of their homes. In Western Massachusetts, that “pro-local” ethic has always been strong. “In the next two months around here, there will be an artists’ open studios event almost every weekend,” she says, and many local boutiques sell regional artists’ wares. People here know that if you don’t buy things from artists and in downtown stores “then they won’t be there anymore," she adds. “And everyone wants to support this community that they love.”