Behind the Scenes: Getting things right

Associate editor Lydialyle Gibson discusses the challenges of writing about people’s lives and the responsibility of conveying their experiences so they would be able to recognize themselves through the writer’s eyes.

It sounds almost too obvious to say: in writing about other people’s lives, the biggest responsibility is to get things right. This is not just a question of facts; it’s also a matter of tone and emphasis and balance, of choosing the truest detail among a dozen objectively true ones. Of representing people’s experiences in a way that feels emotionally accurate—to them and those who know them. That allows them to recognize themselves in the eyes and words of another person.

I don’t always succeed in all of this, but it’s something that I take very seriously and work very hard to do.

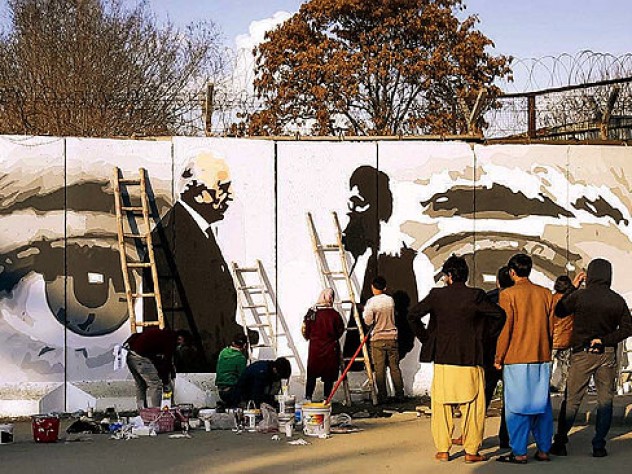

That’s especially true with stories like this issue’s feature about the Scholars at Risk Program, which gives Harvard fellowships to artists and academics around the world whose lives and work are under threat. In reporting this story last fall, I spoke to more than twenty people. Most of them were current and former fellows in the program: a Ugandan human rights lawyer, a Pakistani Islamic studies scholar, a Sri Lankan scientist, a Guatemalan judge, a Nigerian poet, half a dozen physicians and artists and women’s rights activists who’d recently fled Afghanistan. Their lives were the heart of the story. These were people who had known trauma and violence and mortal danger, who were separated from home and loved ones by thousands of miles, who had lived through experiences I could not imagine. At first I wondered if they would trust me with their stories (after all, who was I?), but it quickly became clear that wouldn’t be a problem—they trusted me because they trusted Jane Unrue, the program’s extremely kind and capable director. And she had given them her assurances.

Instead, the more pressing concern for me—which intensified with every interview—was figuring out how to tell their stories well, to convey their memories and thoughts and emotions in a way that was true, even if it couldn’t be comprehensive. In other words, to get things right.

I knew I would have room to include only a small fraction of what I had in my notes and transcripts. Most of the interviews lasted an hour or two, sometimes longer, and people shared stories that were painful and harrowing, and often searingly personal. They also spoke—excitedly, passionately—about their work: the artists and scholars who come to Harvard’s program are extremely talented and accomplished individuals. Unrue regularly says that the University gains more from their presence here than they do, and I believe she is right. I talked at length with robotics engineer Thrishantha Nanayakkara about his research into the “embodied intelligence” of knee joints and inner ears (it’s really cool stuff) and how he is using the data he’s gathered to develop technologies to help farmers in his native Sri Lanka fight off the red palm weevil that has been devastating coconut crops. My conversation with Amna Afreen went on so long that I had to reschedule a train ticket. An Islamic studies scholar who fled Pakistan after her mentor was assassinated, she talked about her new career as a second-grade teacher in a Baltimore public school and the similarities she sees between her students there and the children she grew up with in her lower-class Karachi neighborhood. In both places, she said, “no one’s breaking the chain—it’s generation to generation.” She described what it takes to teach those kids, and what it means to her: “I feel like I’m still serving my community.”

For this feature, part of getting things right—and a really critical part, I realized as the reporting progressed—meant striking the balance between conveying the real anguish fellows had suffered and giving space to who they were outside of those experiences: poets, painters, midwives, doctors, attorneys, researchers. Partly it was important because that’s what Harvard’s program does, too. As Cogan University Professor Stephen Greenblatt, who chairs the program’s faculty committee, told me, when fellows reach the campus, they are not just victims and refugees but “scholars rejoining the academic world.”

I am not sure I got everything right. There are details and decisions I’m still second-guessing. But after the feature was published, one of the fellows I’d interviewed sent me an email. At first, he said, he worried that the story “might center too much on our individual trauma,” but after reading it, he found it “dignified and nuanced and very thorough.” He wrote: “Thank you for bringing so much humanity to our stories.”

I’m grateful for the opportunity to try to tell stories like these, and it is because of readers like you that we’re able to invest this kind of energy into every piece we publish. This story went through three major revisions by the time it was published, and editors Lindsay Mitchell and John Rosenberg gave feedback that was crucial in making the final version much stronger and fuller. It is not at many publications that a writer would be offered the time and support to give a story like this one—and the people in it—the attention they deserve.

Read “To the Rescue”