After I spent a month in hectic and dusty Beijing, Kunming—“the city of Eternal Spring,” the capital of Yunnan province—came as a breath of fresh air, literally and figuratively. Kunming is located in China’s most ethnically and biologically diverse region—the land of the fabled paradise Shangri-La, where magical things happen.

Part of the magic, and the reason I am here, is that Yunnan is home to more than half of China’s 30,000 plant species—almost as many as are found in the entire United States. In 2007, China’s first seed bank for wild plants was built in Kunming to store seeds for conservation and research. Like Noah’s ark, the seeds can be used to reintroduce plants into the wild if they ever disappear. The collection also enables scientists to discover new uses for plants and search the plants' genes for traits like resistance to drought and pests.

Photograph courtesy of Lulu Tsao

Relaxing at the Kunming botanical garden

The seed bank, at the top of a mountain on the grounds of the Kunming Institute of Botany, is a modern U-shaped building of orange brick. Its botanic riches are stored in two rather plain walk-in freezers set at -20 degrees Celsius; at this temperature, the seeds can, in theory, last for hundreds or thousands of years. Upstairs, workers clad in white lab coats record collection data, prepare samples for the herbarium, clean the seeds, and check their viability. Step outside, and you find yourself among bamboo groves and lily ponds, their banks lined with dwarf palm trees, tiger lilies, and even evergreens.

Seed bank is an appropriate name on multiple levels. It is literally a storage place for seeds, but the word “bank” also makes a point about wealth. Entomologist Edward O. Wilson (Harvard's Pellegrino University Professor emeritus) once wrote that countries have three forms of wealth—material, cultural, and biological—but “the essence of the biodiversity problem is that biological wealth is taken much less seriously.” Seed banks are an effort to change this, because we may very well end up “banking” on their contents for food, medicine, and biofuel.

While the Kunming seed bank is only a few years old, I am far from the first Harvard-sponsored visitor to come to Yunnan because of its plants. Joseph Rock, an Austrian American and self-taught expert on Hawaiian flora, preceded me by almost 90 years. Exploring on behalf of Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum, he shipped thousands of plant specimens and seeds back during his many years in the mountains. Rock was an eccentric—among other things, he took a collapsible bathtub on his expeditions—but no one could possibly scoff at the value of his collections and photographs.

I would have liked to hear Rock’s stories of escaping bandits and living with the local Naxi tribes in the Yuelong Xueshan mountain range. Botanists are fun people to talk to. Maybe it’s because they see the world around them with great familiarity, their eyes able to pick out a rhododendron, fir, or cardamom plant where most of us see just another shrub or tree. Sprinkled with Latin names, their conversations turn the ordinary into the exotic. When a Scottish horticulturist in Kunming finds out I am from New Jersey, he breaks into a smile and says, “When I was there, I ate a lot of delicious Vaccinium…what do you call them? Oh yes, cranberries!”

Photograph courtesy of Lulu Tsao

A sample of seeds collected on expeditions

While I am here as a reporter, I feel the seed bank's impact as a science major too. The director, a bamboo expert, laments the lack of seed biologists and the fact that the younger generation is more interested in high-impact papers and molecular biology than plant science. I realize that he is talking about students like me—people who grew up hearing about the Human Genome Project, stem cells, and cloning. Field work doesn’t always seem as glamorous. As the Scottish botanist comments with a laugh, “Some people say it’s many years of a wasted life just going to the mountains and looking at things rather than publishing papers.” For me, the marvel of the seed bank is how it merges cutting-edge, "sexy" biology—like genome sequencing and genetic engineering—with what science meant to me as a child: the naturalist tradition of fossil-hunting, bird-watching, and plant-collecting.

Despite the promise of this approach, the seed collectors face huge challenges. One collector tells me about a dam project in southeast Yunnan that threatened to submerge some critically endangered trees. The trees are on China’s list of protected plants, and the team is working to transplant them because the seeds don’t do well frozen. I ask what they can do about the actual dam, or other projects like it. Can they petition the government? He says this is a difficult topic to discuss. I turn off the recorder. We have been speaking English, but he switches to Chinese. And I listen as he speaks about the bureaucracy of forestry services, the state of environmental awareness in China, the many uncertainties that lie ahead. Still, he is unfazed. Going from place to place in China, he says, you are awed by Nature, and you realize that you can do something for the next generation.

Photograph courtesy of Lulu Tsao

The view out my train window

On the train ride back to Beijing, I have two whole days to think about the seed collector's words. Outside my window the mountains of Yunnan are majestic and radiantly green, the rice steppes layered as if by an artist’s broad brushstrokes. Yet it is only too obvious these are not virgin forests and mountains. Much of the native alpine flora has been replaced by tobacco, corn, or rice, and power lines stretch from tower to tower. Elevated highways are being built, only their concrete pillars in place so far. They remind me of ancient ruins, like the columns of Roman temples, except these pillars are signs of the future rather than remnants of the past.

The trip to Kunming has taken away much of my cynicism about environmentalism in China, but as I look at these mountains, it is clear that seed banks are not enough. Botanists still dream of preserving habitats. In the words of the seed bank’s director, they are the species’ homes. Even if seed banks could store the entire world’s plants (and many seeds are, in fact, not bankable), we cannot put soil conditions, insect pollinators, or the many other essential parts of their environment in freezers. The analogy of Noah’s ark can go only so far: what the story doesn’t tell us is how to recreate habitats after everything is destroyed.

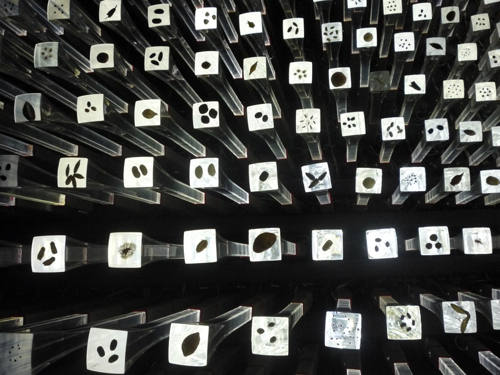

But to preserve habitats, we must care about our biological wealth. This is harder in cities but far from impossible. Two weeks after my trip, during a visit to the Shanghai World Expo, I find myself feeling some of the same awe and reverence as when I drove past Yunnan’s lush mountains. The UK pavilion, also known as the Seed Cathedral, is a fuzzy-looking structure made of 60,000 transparent rods. It would stand out anywhere for its architectural oddness, but its contents are even more special. Embedded at the ends of the rods are seeds from ginseng, tea, maples, magnolias, and many other plants, all provided by the Kunming botanists in a collaboration with the UK-based Millennium Seed Bank. As the seeds twinkle above me like stars, illuminated by LEDs, I cannot help but feel hopeful. If we can celebrate life’s diversity here, in one of the most crowded places on earth, then perhaps it is possible to plant a seed in the minds of people everywhere.

Photograph courtesy of Lulu Tsao

Inside the Seed Cathedral at the Shanghai Expo