“You don’t steal photographs,” explains Leslie Tuttle ’72. “You engage, and the photograph should show something of your relationship to the people in it.”

A social documentary photographer, curator, and archivist, Tuttle has had a lifelong focus on women’s work, in developing countries and closer to home. The former visual and environmental studies concentrator shifted career plans away from architecture when she was introduced to photography at Harvard and fell in love with photojournalism. By her definition, “You’re not [a social documentary photographer] if you think you’re going to go illustrate an idea you already have. You go look for the story, and you listen, and you see what the story is once you get there, and then you document it.”

With this in mind, Tuttle decided to live overseas after graduation “and see the world from a different perspective.” She was offered a job documenting agricultural projects in rural villages in Turkey, and went, intending to stay one year—but she learned Turkish, and the single year stretched to four. That experience with rural communities launched her into a job with Oxfam America. Traveling from Cambodia to India to Mali, she continued narrating stories through images and writing, trying to condense complex circumstances into pieces that were understandable, but not oversimplified.

Gaining entry into private communities with vastly different social expectations is central to doing her work properly, Tuttle explains, especially when her focus involves observing people in their everyday lives. She stresses the importance of honoring lo- cal culture, whether that means dressing conservatively or taking off shoes indoors: “You can avoid barriers if you show that kind of respect. I think in a lot of places I would have been rejected or shunned if I hadn’t done something as simple as covering my head.”

After Oxfam, Tuttle changed gears, “got an M.B.A., had children, and started a nonprofit with my husband,” the Consensus Building Institute. But several years later, when asked to do a photo exhibit about Turkey, she opened up her dark room and printed 60 black and white images from the mid 1970s for display in London and Istanbul. She credits those shows with returning her to the roots of her career. Since then, she has worked for organizations that allow her to photograph, curate exhibits, and create new materials. In 2000, she began an independent project in Turkey, connecting with some of the women she’d met in the mid 1970s, and their daughters. In photos and interviews, she has documented a remarkable generational change. Many of the older women married young, with relatively few resources; their daughters are “getting education, getting birth control, [and] making their own life choices.” She calls the project her “unpublished book”; its working title is “Don’t Judge a Woman by Her Headscarf.”

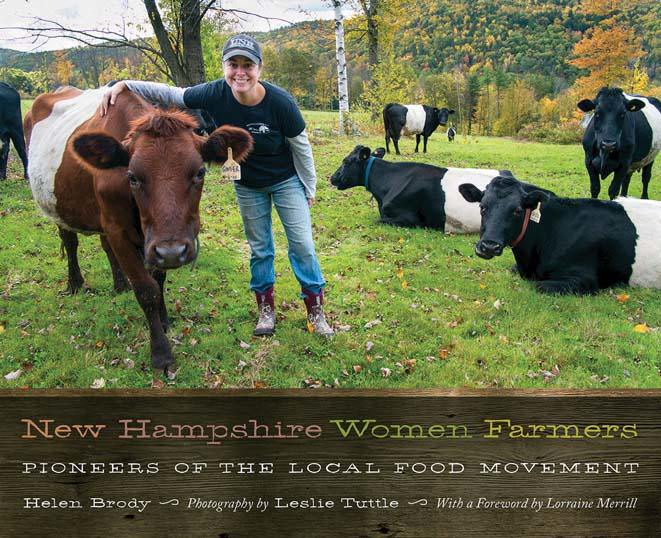

In 2013, she saw a chance to work on a local project about New Hampshire farms. She and Helen Brody, a friend with a background in food writing and local agricultural concerns, produced New Hampshire Women Farmers: Pioneers of the Local Food Movement (University Press of New England), published last fall. They didn’t initially focus on women, but during their research, she and Brody realized that many factors supporting farm prosperity—adding value to the product, promoting farmers’ markets, and interacting directly with customers—were strongly driven by women. “We never said that the men aren’t involved...there are lots of exceptions and lots of partnerships,” Tuttle explains. “But a lot of the women are doing the things that are pushing the local food movement.”

At the New Hampshire Farm and Forest Expo, she and Brody spoke with commissioner of agriculture Lorraine Stuart Mill, U.S. senator Jeanne Shaheen, and Governor Maggie Hassan about how their material could be used for “everything from running workshops for young farmers to tourism”; the pair hope to design an exhibit for the state Department of Agriculture to further these causes. “I didn’t want this book to be just another picturesque rendering of the New England countryside,” Tuttle writes, but instead a “tribute to women,” sharing their stories and telling their tales.