Ten years after his graduation from law school, Michael J. Lyon, J.D. ’84, took his first European bike trip. He wanted to spend time riding alongside his uncle, an eclectic, intelligent man who had taken several bike trips through Eastern Europe, among other unique expeditions, during the Cold War. Lyon planned a trip for France. He found a good route—from Bordeaux, through the French Basque area, over the Pyrenees—and flew with his uncle to Paris, their bikes packed in large boxes. “All I had was a magazine article and a map,” he says. “We just started out, and we rode.”

Cycling through the Pyrenees was tough for Lyon, then 34, and especially challenging for his 66-year-old uncle as the trail steepened and rain fell. “But we loved being together and we loved the trip,” Lyon says. “It was a great bonding experience, full of amazing sights and great food. So when I came back, I started doing research,” he continues. “What kind of trips could we do together?”

Lyon began collecting German guidebooks and searching for flat, car-free bike trails they could try next time, and decided on a path along the Rhine. He and his uncle repeated the process every year thereafter. When he returned from Europe each summer, friends asked him how he managed to organize such complex trips. “And I said, ‘It’s not complicated, it’s not expensive. Anybody can do it, if you’re a little adventurous and like exploring.’”

Lyon decided to write a book about his experiences and methods. In Cycling Along Europe’s Rivers, first published in 2012 and updated this year, he takes a straight-forward, step-by-step guide to planning and executing bike trips across Europe. Before getting into specific trail recommendations along the Rhine, Danube, and Elbe (among others), he prepares the reader for each step of the trip—from bike-transport logistics to hotels to bicycle, packing, and clothing suggestions. He compares the book’s style to that of a business plan, a genre he’s become familiar with as a general counsel, business owner, and space-tourism entrepreneur. He fits about 70 routes into the book, each with pointers on food, lodging, and fun for a few days to a few weeks of riding between 30 and 55 miles a day. Lyon hopes the direct approach emboldens people to try a trip themselves. In his new release, Cycling Europe: Great Day Rides, he provides shorter itineraries for those who want to spend more time in a single city.

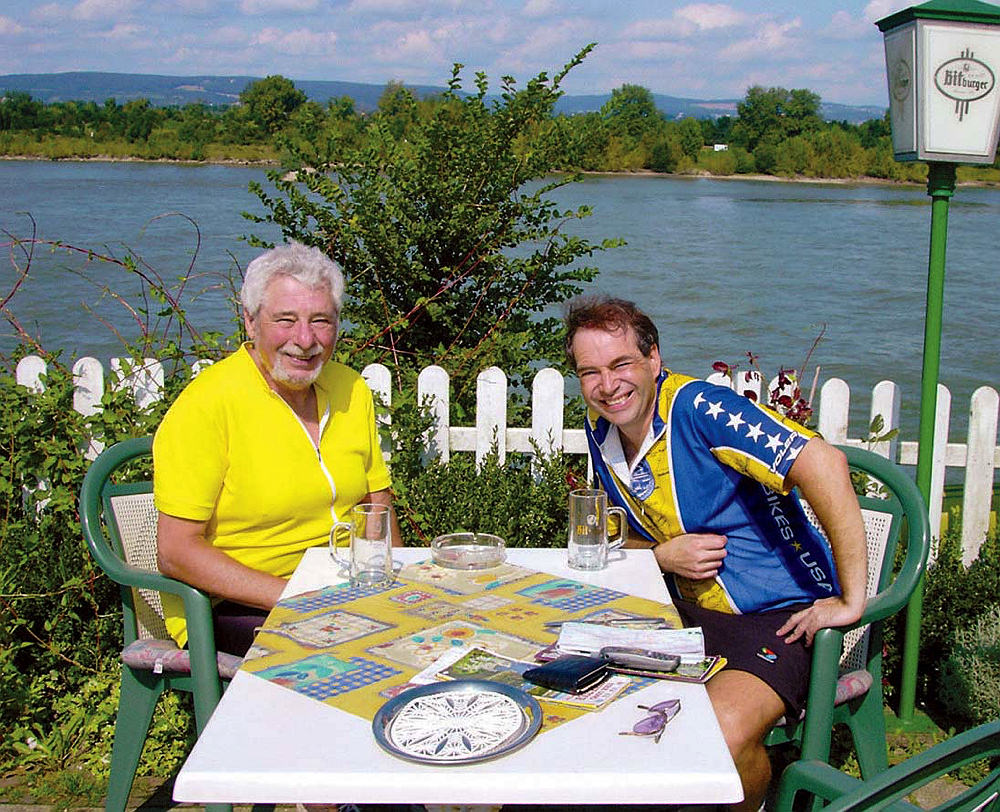

A brief biking break with Uncle Harvey (’49, Ph.D ’56), who inspired his first European cycling trips.

Photograph courtesy of Michael J. Lyon

Once people experience the virtues of European cycling, Lyon finds, they’re hooked. Many trails are well-maintained and relatively flat, major cities are often a short bike ride away, and historical sites are plentiful along any river. Tour boats make it possible for tired riders to take breaks while keeping up with the group. He thinks a bike is the best way to travel on vacation: quick enough to cover a lot of ground, but not so fast that visitors miss important sights en route. Plus, he likes being able to “eat with impunity.” “Most vacations, you come back maybe not feeling as good as you did when you started,” he says. “With this, you get in shape.” Staying in inexpensive two- or three-star hotels most nights keeps expenses down and enables him to splurge on a few exceptional experiences, like a top-notch dinner after an exhausting day or a night in a room that once accommodated Napoleon. (“The bed felt like Napoleon might have used it. It was really horrible,” he jokes, “but it was so cool.”)

For Lyon, though, the itinerary of the trip is less important than the company. “My uncle and I, we just had the most magical time riding together,” he says. One of his favorite memories is the trip he was able to take with his eight-year-old son, Joshua, and uncle, then 85, in 2013, a few years before his death. “For me, having that relationship, that time together, talking about politics and family and the place we’re at—it’s just something I’ll cherish for the rest of my life.”

Since then, he’s taken a trip each summer with Joshua, on a tandem bicycle that allows them to chat constantly as they ride. During the 2013 outing, Joshua could fall asleep in the recumbent seat at the front when he got tired, but he helped boost his father’s pedaling on uphill climbs. When Joshua got a bit older, they drilled multiplication tables together. Lyon hopes that in a couple years, Joshua might take a gap year before college so they could try a longer trip together before school and work get in the way. When you’re able to do something that you love with your child, Lyon says, “You’ve won already. At that point, my job is to make that experience as good for him as possible.”