The race to send humans to Mars is underway. That’s the sense conveyed by certain politicians and wealthy entrepreneurs, who have spoken broadly about creating a Red Planet outpost. The website of the U.S. federal space agency, NASA, echoes that optimism, citing its work on “many technologies to send astronauts to Mars as early as the 2030s.”

That goal is staggeringly ambitious. Setting aside the astronomical price tag (and the question of who would foot the bill), a trip to Mars would represent a massive leap in the science of space exploration. The International Space Station (ISS), in operation for more than two decades, orbits just 250 miles above Earth. Mars lies more than 250 million miles away—roughly a thousand times farther than the Moon. The journey alone would take six to nine months.

On Mars, the challenges would multiply. The planet has an ultra-thin atmosphere—its density is just 1 percent that of Earth’s—combined with a gravitational force that’s less than half as powerful as Earth’s and temperatures that can drop to -225 degrees Fahrenheit. To survive, astronauts would need to create entirely new habitats, with protective shelters and sustainable food sources.

But among a subset of researchers, engineers, business executives, and true believers, minds are whirring. NASA’s Artemis program, aimed at returning astronauts to the Moon, also serves as a test bed for the technologies required for a future crewed mission to Mars. Faculty and alumni across Harvard’s schools and disciplines have been among those tackling the challenges astronauts would face if they traveled to the Red Planet…and stayed.

Some of it is long-term work. But as it turns out, much of the research and innovation that could eventually get humans safely to Mars has the potential to improve life here on Earth in the near future.

The Long Journey to Mars

The first hurdle to a manned Mars mission would be ensuring that humans are physically prepared for the trip. Space travel is notoriously taxing on the body: without gravity loading the muscles and bones, astronauts on long space missions experience profound physical changes, including muscle wasting, bone loss, immune suppression, and cardiac strain. On the ISS, daily resistance training and precise nutrition help offset these effects, but just barely.

Alfred Goldberg, a longtime professor of cell biology at Harvard Medical School who died in 2023, was a pioneer in uncovering how and why muscles break down. In 2001, his lab identified atrogin-1, a gene that plays a central role in driving muscle atrophy. The gene becomes highly active both in microgravity, where the absence of mechanical load causes muscles to weaken, and in certain diseases including cancer and AIDS, when the body undergoes rapid muscle wasting. Goldberg’s findings helped establish why regular physical activity is crucial for maintaining muscle mass and for counteracting the muscle-loss effects of weightlessness.

Nutrition, especially protein intake, also becomes a precision science in space. Astronauts must maintain sufficient amino acids in their bloodstream to sustain muscle mass, while also managing hydration and a limited supply of food.

“It’s like being an aging adult or elite athlete on a space station,” says Jennifer Sacheck, a former postdoctoral researcher in Goldberg’s lab who is now a professor at Brown University. “The same rules apply, just faster and with higher stakes.”

For the months-long journey to another planet, one radical solution is induced hibernation: placing astronauts into a torpor-like state that slows metabolism, preserves muscle and organ function, stabilizes neurochemical activity, and significantly reduces food, water, and life-support needs.

“You protect the body, calm the mind, and buy yourself more time to survive.”

“It’s a multi-system solution to multi-system risks,” says Ekaterina Kostioukhina, A.L.M. ’21. “You protect the body, calm the mind, and buy yourself more time to survive.”

Kostioukhina, a medical doctor, hopes to help bring that sci-fi technology into reality—inspired by a course she took while earning her master’s degree in psychology called “Brain and Behavior in the Extremes.” After graduating in 2021, she launched HIBERIA, a platform where scientists worldwide can collaborate and share knowledge on human hibernation for deep space missions. (The name stands for Hibernation Intelligence Base for Education Research and International Alliance.)

Kostioukhina says she is inspired by research from the lab of Elie Adam, a member of Harvard Medical School’s department of anesthesia who studies the interplay of anesthesia and human metabolism. Another inspiration is the MIT lab of Sinisa Hrvatin ’07, Ph.D. ’13, a former postdoctoral researcher of Pusey professor of neurobiology Michael E. Greenberg. Hrvatin’s team examines neurons concentrated in the brain’s hypothalamus that are capable of triggering torpor-like states in rodents—research that, Kostioukhina suggests, could someday be used to develop practical tools to slow human metabolism during spaceflight.

The same breakthroughs that would help astronauts survive a Mars mission could aid trauma victims, organ transplant patients, or hospital intensive care units, where inducing a torpor-like state could reduce metabolic stress in individuals with sepsis or multi-organ failure.

And understanding how hibernators protect their organs and maintain functionality during extended periods of inactivity could inform treatments for widespread diseases like obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular conditions, Alzheimer’s, chronic kidney disease, and more. “What if we could suspend biological activity in the human brain to protect it after a stroke and reanimate it in safe conditions?” the Adam lab asks on its website.

Other innovations in space medicine stem from the isolation astronauts would face if something went wrong. In space, “there’s no hospital down the hall, no resupply on demand,” Kostioukhina says, “and no margin for error.” As much as possible, the focus of medicine must shift toward prevention, rather than treatment after illness or injury occurs.

Emerging technologies such as AI-assisted monitoring, wearable biosensors, and automated health management systems could enable early detection of health problems and provide health services when clinicians are thousands—or millions—of miles away, Kostioukhina explains.

These technological interventions may also prove useful for people living in remote or underserved regions on Earth, helping to automate processes when there’s a shortage of clinicians or medical facilities. Examples include digital and AI-driven diagnostic tools that analyze vital signs in real time and compact “lab-in-a-box” kits capable of performing blood and saliva tests autonomously.

Growing Your Home on Mars

Imagine that astronauts make it safely to Mars (and wake up from their slumber). Once there, they would need safe, long-lasting places to live. These should be habitats that can endure the planet’s extreme cold, radiation, and isolation—heavily shielded, industrial structures, which would be expensive and challenging to fly in from Earth. But recently, some Harvard researchers have been asking a more radical question: what if we could grow our habitats instead?

McKay professor of environmental science and engineering Robin Wordsworth has been developing real-life solutions on planetary habitability, using creative combinations of climate modeling and materials to explore how alien worlds such as Mars could sustain life.

In 2019, Wordsworth and his team’s findings were published in Nature Astronomy, describing how a thin layer of silica aerogel—a lightweight, translucent insulator—could create pockets of habitability on the Martian surface. The aerogel would act like a localized greenhouse, letting in visible light, trapping heat, and blocking harmful ultraviolet radiation.

“In theory, just a few centimeters of aerogel could raise temperatures by 50 to 60 degrees Celsius,” Wordsworth says. “That’s enough to create melting conditions for water and support photosynthetic life beneath.”

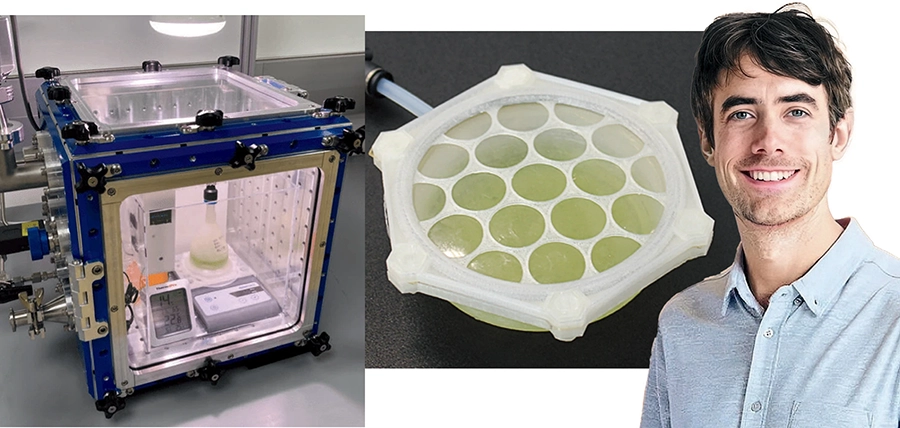

More recently, in July 2025, Wordsworth’s lab proposed a novel habitat made from bioplastics created partially or entirely from plants. In experiments described in the journal Science, they created 3D-printed chambers using polylactic acid—a biodegradable material derived from plant starches—and grew a common type of green algae called Dunaliella tertiolecta inside them under Mars-like conditions. Despite the harsh conditions of the simulation (low pressure, high radiation, and frigid temperatures), the algae survived. Not only that, they even photosynthesized, generating oxygen and remaining stable.

“There’s no reason why this couldn’t work for the vast majority of plant species,” says Wordsworth. “We’re showing that biology can be the basis for construction, life support, and even future growth.” Perhaps most intriguing, the algae could be used to create more bioplastics, essentially forming a closed-loop system in which habitats expand and repair themselves using Martian sunlight and local resources.

“Imagine a structure that grows itself,” Wordsworth says. “You land with the seed components, and it builds over time. That’s a future worth designing.”

The team plans to test its bioplastic chambers next in vacuum chambers and extreme Earth-based environments, such as high-altitude deserts. “With the right political will and the right organization,” Wordsworth says, “we could do these things pretty quickly.”

What’s more, while synthetic materials break down and pollute over time, bioplastic habitats could be recycled through bioreactors that use microorganisms or enzymes to decompose the plastic into its base organic components, which could then be used to produce new materials. Wordsworth says bioreactor technology could also help reduce pollution on Earth, potentially limiting the accumulation of plastic waste in landfills and oceans and cutting down on fossil fuel use for new plastic production.

Paying Humanity’s Way to Mars

Emerging technologies may eventually solve the “how” of getting astronauts to Mars. A separate dilemma is who will pay for it—and how to generate the political will for such a costly endeavor. NASA’s budget today hovers at less than half a percent of federal spending in the United States, compared with about 4 percent during the Apollo era of the 1960s and ’70s when the Moon program consumed roughly $25 billion (a value exceeding $100 billion in today’s dollars).

A full-scale Mars mission would be far more expensive and stretch across decades. Artemis, NASA’s new Moon landing effort, which will test long-duration habitats and life-support systems that could enable a Mars trip, is projected to cost $93 billion through 2025.

“Success depends on a very close and symbiotic relationship between NASA and the commercial space sector.”

“Success depends on a very close and symbiotic relationship between NASA and the commercial space sector,” Harvard Kennedy School professor John Holdren, a former White House science advisor, said at the Human Spaceflight Symposium held in Boston in October 2025.

The commercial space sector has grown dramatically since Ariane Cornell, M.B.A. ’14, helped form the first aerospace club at Harvard Business School. Now, as vice president of strategy and business operations at the aerospace company Blue Origin, Cornell is working to create the conditions that would make ambitious space missions financially sustainable. Currently, she oversees the company’s New Glenn program, which aims to build a heavy-lift reusable rocket that could deliver cargo—and eventually, people—into orbit and beyond.

Cornell argues that building Mars infrastructure will depend on the same kind of layered economic ecosystem that made the internet possible. “Amazon wasn’t possible without credit cards, broadband, or FedEx,” she says. “Space needs the same rails—rockets, supply chains, regulatory frameworks—to unlock what comes next.”

While Blue Origin and SpaceX—founded by billionaires Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk, respectively—generate some of the biggest headlines, many other aerospace companies have emerged to fill portions of the space-race supply chain. David Andrade ’22, an engineer at the aerospace company Rocket Lab, believes the key to making Mars affordable is standardization: turning space hardware into mass-producible, swappable systems rather than bespoke, billion-dollar prototypes. “Think of spark plugs or alternators,” he says. “You don’t reinvent them for every vehicle—you build around them.” His team is also working to make rocket production faster and cheaper by reusing engine parts.

Both Cornell and Andrade acknowledge that private innovation alone won’t get humans to Mars. The global space economy, projected to surpass $1.8 trillion by 2035 according to a 2024 Mc-Kinsey report, remains largely Earth-bound, focused on satellites, navigation, and climate observation. Human exploration yields less immediate profit, making long-term partnerships essential.

“No single nation can afford a three-year Mars mission alone,” said former NASA advisor Rebekah Reed, who now serves as the associate director of the program on emerging techno-logy, scientific advancement, and global policy at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, to the crowd at the Boston spaceflight symposium. “We need to understand and share risk—vehicle risk, human risk—across borders.”

These costs and risks raise the question, for some, of whether humanity should aim to go to Mars at all.

These costs and risks raise the question, for some, of whether humanity should aim to go to Mars at all. Does spaceflight distract us from Earth’s acute crises: inequality, climate change, resource depletion? Why reach for Mars when our own planet needs saving?

Those questions have persisted during the nearly 75 years that humans have aimed to travel beyond Earth. In her 1963 essay, “The Conquest of Space and the Stature of Man,” written at the height of the U.S.-Soviet space race, philosopher Hannah Arendt asked whether the drive to conquer space would expand or erode our sense of human purpose.

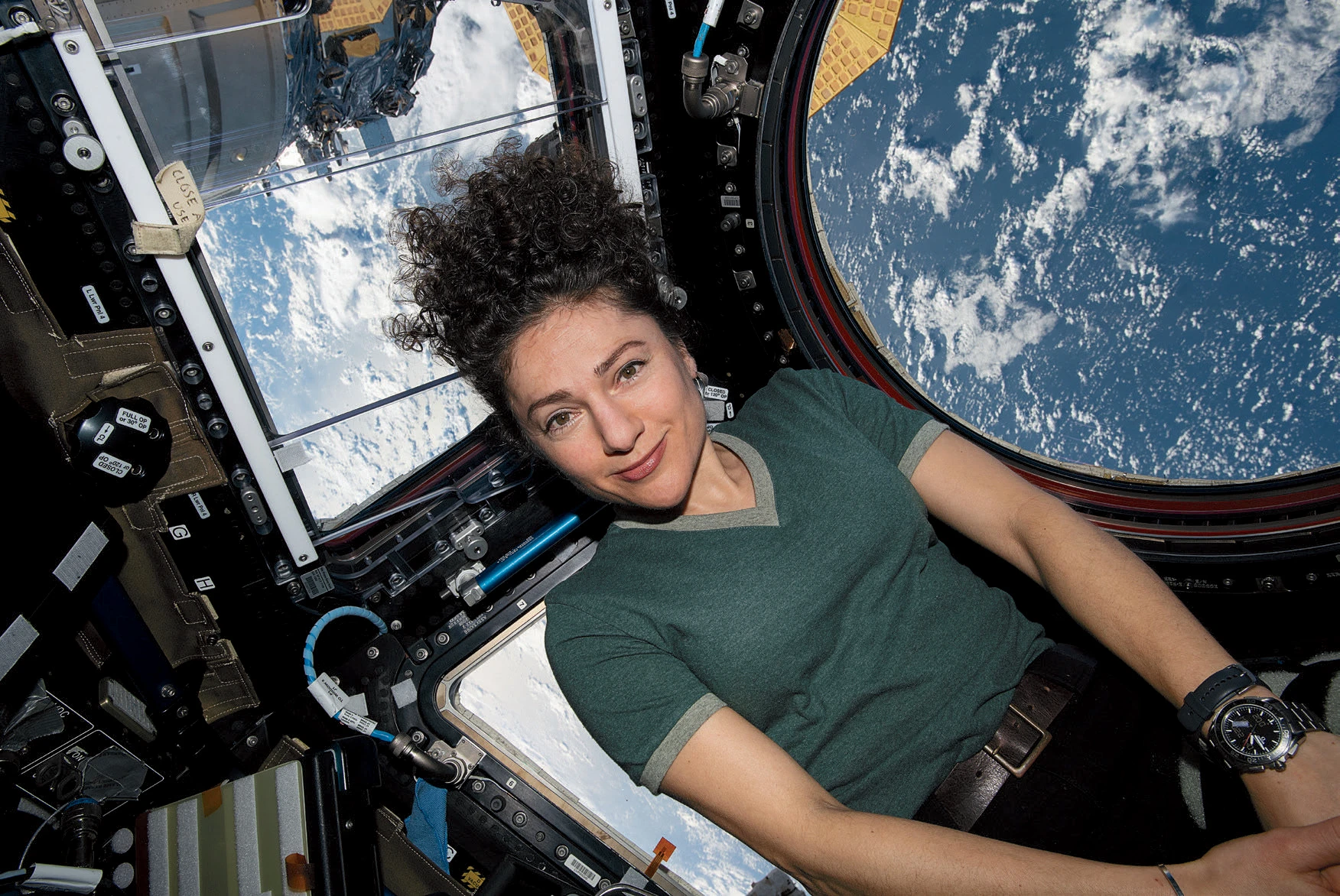

Mars mission proponents say the answer lies in what space gives back—to science, society, and the soul. “I really do believe it’s just part of us as humans,” says Jessica Meir, a former assistant professor of anesthesiology at Harvard Medical School who spent more than 200 days in orbit on the International Space Station in 2019 and 2020.

Meir, who was recruited to NASA in 2013 and previously studied how mammals survive in extreme environments, took part in the first all-female spacewalk in 2019, gazing at Earth from beyond its atmosphere. Her time on the ISS, in close quarters with the international crew, gave her perspective on the psychological and physical challenges of working in space for extended periods—but also, a renewed commitment to the purpose underlying space missions generally. Part of the value of a space program is practical, she says, “investing in STEM, dreaming big, working together”—and making discoveries from moon rocks to medical breakthroughs.

But Meir sees some deeper value, too, in imagining life beyond our planet.

“There’s something intangible about what [space travel] does for us as a society,” Meir says. “It’s the intrinsic nature we have to look around the corner.”