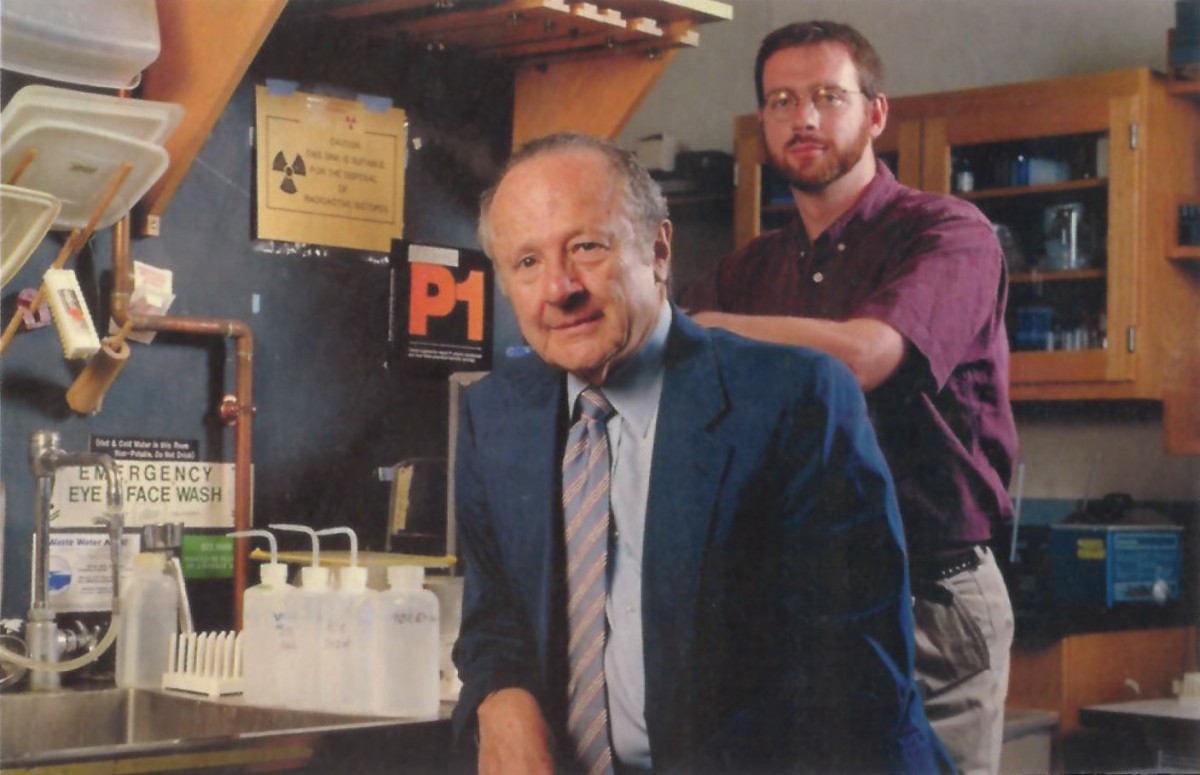

Birds do it. Bees do it. Bdelloid rotifers, it seems, eschew it. Not love, that is, but sex, which these multi-celled freshwater invertebrates have not had in perhaps 80 million years, say Cabot professor of the natural sciences Matthew Meselson and post-doctoral fellow David Mark Welch, Ph.D. '99, who report the evidence in Science magazine.

The discovery is more than just a sexual oddity--biologists call it an evolutionary scandal. Creatures that can reproduce without sex have arisen sporadically throughout history, but the fossil record and other evidence show that within several thousand years they become extinct. "It's clear that creatures originate every once in a while that can reproduce without fertilization," says Meselson. "The female's eggs just hatch. This has happened in many insects, and in some fishes, snakes, and lizards." But once males disappear, even though the species may do better than its sexual progenitors for a while, it eventually becomes extinct. Mark Welch's and Meselson's new evidence for bdelloid (pronounced like "deltoid" without the "t") rotifers' multimillion-year abstinence raises anew the questions, Why is sex necessary for most life, and why not for the bdelloids?

Meselson and Mark Welch studied four genes in four species of bdelloids. (There are about 360 bdelloid species, all reproducing asexually, and all thought to be descended from a common female ancestor.) Sexual organisms carry two copies of any given gene, each supplied by one parent. But in asexual organisms, there is only one parent, which supplies its offspring with both of its own copies. In each subsequent generation, the two copies of the gene are reproduced. Over time, tiny mistakes in the copying process can independently accumulate in each gene (if the mutations are not fatal). After many millions of years, the difference betwen the two copies will have become far greater than it is in sexually-reproducing species. This is exactly what Mark Welch and Meselson found. Using standard rates of mutation in other animals, they estimate that the common female ancestor of all bdelloid rotifers lived 50 million to 100 million years ago.

That's a long time to go without sex, which biologists define not as copulation, but as DNA exchange between organisms. As early as 1887, August Weismann recognized the cost of sex, and hypothesized that sex must therefore confer important advantages on its practitioners. "If we bear in mind that in sexual propagation twice as many individuals are required to produce any number of descendants, and if we further remember the important morphological differentiations which must take place in order to render sexual propagation possible," Weissman wrote in the journal Nature, "we are led to the conviction that sexual propagation must confer immense benefits upon organic life. I believe that...sexual propagation may be regarded as a source of individual variability, furnishing material for the operation of natural selection." To this day, Weissman's argument for why sex is costly, and his hypothesis about what benefits sex confers, remain popular.

An alternative hypothesis is that of the "Red Queen." In Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking- Glass, the Red Queen tells Alice, "Now here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place." To biologists, this idea of running in place aptly describes a parasite-host relationship. The parasite adapts to attack its host--and the host adapts to resist being eaten by the parasite--in an ongoing, inherently tense dynamic of constant keeping-up, a striving to avoid the loss of fitness, in both organisms. Sex increases the rate of genetic variation, which is, from the host's perspective, an advantage in fending off parasites--and an advantage to parasites in remaining able to attack the host.

A different type of hypothesis to account for the predominance of sex, one that Meselson's laboratory is currently exploring, holds that sex somehow purges the genome of deleterious mutations. But many biologists who have pondered the problem, says Meselson, would agree that we do not yet know why sex exists.

"What good is sex doing for 99.9 percent of living creatures?" Meselson asks. "Or, put differently, what is it that goes wrong with most asexual species, causing their early extinction? It's very strange that there is this one huge exception--the bdelloid rotifers--to what otherwise appears to be a universal rule. The answers to such fundamental questions," he says, "must lie very deep in the bedrock of biology."

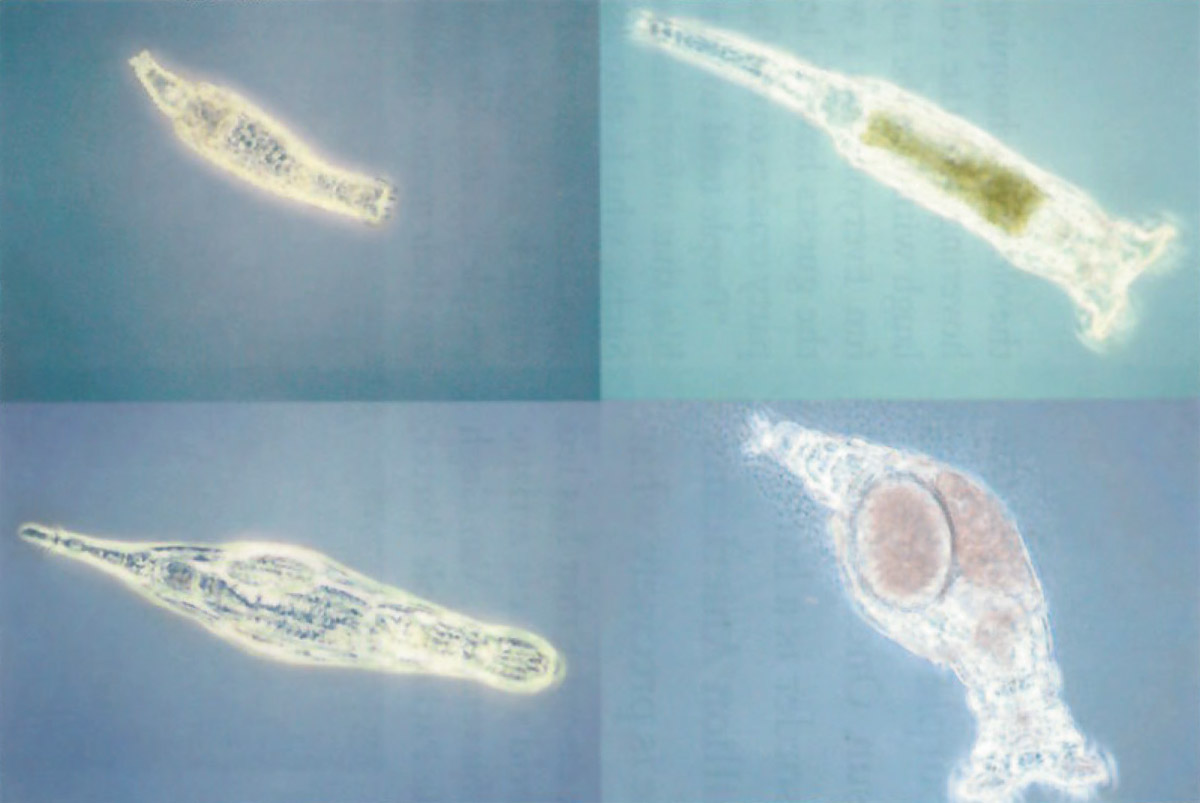

There are no males among the 360 described species of bdelloid rotifers, and no evidence of sexual reproduction has ever been found. Above, four species of bdelloid rotifers. The female at top left is eating algae; an egg is visible in the rotifer on the upper right.

Photographs by the Meselson Laboratory