|

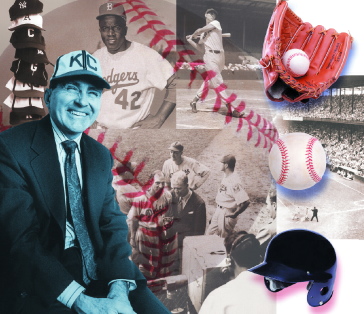

| Portrait by Flint Born. Photomontage by Bartek Malysa. Historical photographs courtesy of Associated Press. |

As the class settles in for the lecture, William E. Gienapp reaches into a plastic bag beside the lectern and pulls out a white baseball cap bearing a red "C" in Old English script. "My hat for today," he begins, "is the 1869 Cincinnati Red Stockings." He holds it up for the class to see and there is a brief murmur of approval. ("The kids seem to enjoy it," he will explain later, sitting in his office in Robinson Hall, where a collection of early baseball caps hangs from the wall. "I enjoy showing them a cap and it will be clear by the end of the class why I picked it.") Then he puts the cap on his head, tugs on the peak, adjusts the reading spectacles perched on the end of his nose, and gets on with the serious business of teaching History 1653, "Baseball and American Society, 1840-Present," which examines the relationship between baseball and the development of American society and culture.

Gienapp's official specialty is the Civil War. "Like a lot of little boys, I was very interested in warfare," he says. "I thought the Civil War was this great dramatic event. As I became older and studied it, I became interested in other aspects of the war, but never lost interest in the war itself."

Two friends who had taught a course on sports and society suggested the idea to him as a change of pace. "I was very dubious that it could be done as a true history course," Gienapp says now. "But they were both historians and said that would be no problem, that I'd have many more topics to talk about than I'd have time. I decided to limit it to baseball because I was most interested in that sport. Baseball also has an advantage: it has a long history and you can go way back. Football and basketball are twentieth-century sports."

He taught the course twice as an undergraduate seminar before offering it as a lecture course. "Too many students wanted to take it and it was too difficult selecting the students for the seminar," he says. "The ones who didn't get in were very unhappy." Word is out on campus that this is a hard course, he adds, but "there is always a group that shows up on the first day under the misapprehension" that it is a celebration of great players and exciting pennant races.

On this day, the class is hearing about the professional movement in the United States and its impact on competition and commercialism in baseball. After the Civil War, Gienapp says, lawyers, doctors, accountants, librarians, social workers, and other professionals wanting to set themselves apart from the working class formed organizations such as the American Bar Association. Policemen and firemen began to distinguish themselves by wearing uniforms. Baseball followed this pattern.

In 1860, James Creighton, a lanky, 19-year-old pitcher for the Brooklyn Excelsiors, was baseball's first real star player and the first to be paid a salary. In 1869, the Cincinnati Red Stockings became the first all-professional team, with salaries ranging from $600 to $1,400. A remarkable team it was: barnstorming 11,000 miles around the country, playing the very best local teams, winning 56 games and tying one. But the next season, when the team lost six games, the fans in Cincinnati became disillusioned and the team was disbanded. In 1871, ballplayers established their own organization, the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players, which endorsed playing for pay. It was the sport's first step toward becoming a business. The original game, in which the emphasis was on recreation and a high standard of decorum, gave way to a lust for victory. The open "Elysian Fields" of the game's early days were enclosed by fences, an admission fee was established, the fans and players alike became increasingly rowdy, and gambling flourished.

"Baseball's hold on middle-class respectability, on the Victorian ideal, was always tenuous," says Gienapp, "and baseball was now linked in the public mind with other working-class sports like boxing."

Gienapp (pronounced g'napp), 56, has the short, wiry build of a second baseman. He lectures at a rapid pace, settling into a rhythm that evokes the image of a bench jockey trying to talk up a little hustle around the infield.

Growing up in Mingo, Iowa, a farm community 30 miles from Des Moines, young Bill played ball "for hours as a kid," but never on school teams. His father was superintendent of schools and a devout baseball fan. "He loved the St. Louis Cardinals and once drove all the way to St. Louis to see Rogers Hornsby play. My mother was a lifelong Cubs fan and my great-aunt must have listened to every Chicago White Sox game on the radio. I was torn among all those teams." (Today, he admits to being a Red Sox fan, a decision made to give his then five-year-old son a chance to develop a loyalty to the local team after the family moved here in 1989.)

"I followed baseball the way most Americans did who didn't live in a major-league city, through the radio and the newspaper, and then television," he says. "There was no team in Iowa, so you don't have that kind of 'identification.' There is nothing like sports to symbolize a community and unite people. People don't brag about their art museum or the public library, but something about sports can transcend all that and become a much more important symbol for the community than its true importance would warrant."

At 13, Gienapp moved with his family to Orange County, California. He was an undergraduate history major at the University of CaliforniaBerkeley, earned his master's degree in history at Yale, and returned to Berkeley for his Ph.D. He taught history there and later at the University of Wyoming before coming to Harvard.

It is the early days of the sport that fascinate Gienapp--the scholar working his subject as history and creating a context in which to understand the modern game. "I wish I could have seen the game in the first years of the twentieth century," he says. "The crowds were smaller, but they were really fanatical fans, arguing all the time about the merits of every player and every play. They hung on every pitch. Well, it's not like that any more. The intensity of the fans isn't there any more. The season is too long. It is only in the last month that, for the teams in the race, it seems like life and death. Of course, in Boston, when they play the Yankees, the intensity is there for every game."

He finds baseball lagging increasingly behind changes in society, but eventually responding to them. "Our society has become a much faster society and baseball is a slow game. That hurts baseball. The owners always talk about the need to speed up the game, but they don't do a damn thing."

Gienapp suggests many themes that link baseball to the larger world. "I talk about civil rights and Jackie Robinson. Why the West grows after World War II--how the American population is spreading west and the Dodgers go west. How television changes the game, its popularity. The relationship between women and the game. In the 1920s, when women become much more independent, much more assertive, you see a real surge in women's attendance at the games. Why then, why not earlier when baseball tried so hard to recruit women? We look at struggles between the players and the owners over the control of the game."

Gienapp's reading list for the course keeps the focus on the history of baseball and its relationship to society. He includes books that "talk about historical questions, that are not just recountings of some season or pennant race. I also try to get the students to read something from the period." He mentions Lawrence Ritter's The Glory of Their Times (an oral history in which players from the first two decades of the last century tell their own stories) and Jim Bouton's Ball Four as important books "written by people in the game, as opposed to historians just talking about the game."

He considers the Bouton book a significant social document because it changed public understanding of the true nature of the game. "One of the things we do is examine why this book was so controversial" at the time it was published in 1970, "when it seems so tame to us" today. Bouton, a pitcher for the Yankees, did not portray players as the "upstanding citizens that baseball wanted the public to believe them to be. The owners and the players never have lived up to the image of baseball as a competitive, respectable, upright, clean kind of sport." Another part of the image that has fallen away, Gienapp says, is the belief that there is "a real link between the fans and the players. None of that is true any more." Ball Four, he continues, also helped change the culture of sports writing--the relationship between the press and the players--much in the way the coverage of Washington changed after Watergate. "The press was much more relentless in pursuing the shortcomings of players and owners" after Bouton opened the door.

Gienapp laments the declining position of baseball in our modern culture. "I think the downward trend could be made less steep if the game were regulated better," he says. "The fundamental problems are endemic to the society and beyond the game itself. It has been hurt by television. It doesn't televise well as a game, compared to basketball and football. It is hurt by the fact that it has no time limits. It can go very late into the night, and that discourages parents with young children from going to games. It is hurt by the fact that it's a hard sport that takes an enormous amount of skill to play decently as a young person. If you can't hit the ball or you can't catch it or you throw it away, you're not going to have a great time. Children who don't develop that skill quickly don't continue to play it. The fans have always been people who played it as children."

Like Gienapp and many of his students. Asked what he gets from teaching the course, he replies, "I enjoy getting the student comments, because nearly everybody taking the course probably has some connection to baseball. Some students are bigger fans than others, but they all like the game, so you are teaching them about something they already know, something they already like. I enjoy talking about a subject that covers 150 years of American history. I like showing students a different way to look at American history. I try to show them they can learn things about this country from looking at what they don't think of as traditional historical topics, like sports, and how many different parts of our history baseball has intersected with."