|

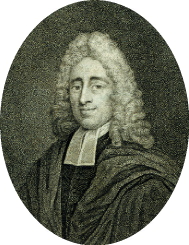

| Increase Mather was already presiding over Harvard College when he received one of its first honorary degrees. (More recent presidents have generally had to wait a year after leaving office before receiving the honor.) |

| Image courtesy of the Harvard University Archives |

The identities of the honorands--held close to the vest until they are announced with much fanfare on Commencement day--fuel excited speculation. A standing committee of the Corporation investigates the qualifications of the nominees and then submits a honed list to the full board for approval. A unanimous vote is typically required. The final list is passed to the Overseers for confirmation. On average, 10 honorands are selected each year and they are required to be present at Commencement to receive their degrees.

Perusing the hundreds of archival documents related to Harvard's honorands turns up well-known recipients and others whose contemporary renown does not survive today.

The Reverend Dr. John Snelling Popkin, A.B. 1792, A.M. 1795, for example, received his honorary degree in 1815. He served as professor of Greek language from 1815 to 1826, when he was appointed Eliot professor of Greek literature, succeeding Edward Everett. That his influence was great in his own day, if not in ours, is evidenced in a letter of unknown authorship stored in the archives. "So lived and so died Dr. Popkin, a man of rare abilities who shunned the public eye, but put the stamp of his fine qualities...of character on the minds of many distinguished men who have been educated...at Harvard College. Signed, F."

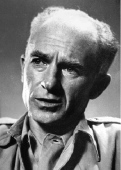

A little more than a century later, in 1938, Harvard awarded an honorary Master of Arts degree to Walter Elias Disney. "We're selling corn," Disney wrote to President James B. Conant in response to the letter offering him the degree, "and I like corn. I try to entertain, not educate: an important part of education is stimulating an interest in things."

Disney's honorary degree citation read: "A magician who has created a modern dwelling for the Muses." But even though he stole the show at Commencement, Disney was not without detractors. A short while later, the following telegram arrived from a member of the class of 1910:

Dean of Harvard University

Dont phone CA=

I object to the cheapness youre showing in giving degrees to men like Disney who make a farce out of it. When mothers like mine have self sacrificed themselves to make Harvard men. Why go to college=

|

| Walter Elias Disney stole the show when he was honored in 1938, but not everyone approved of his selection. |

| Image courtesy of the Harvard University Archives |

Selflessness and self-sacrifice are qualities often rewarded by an honorary degree. World War II correspondent Ernest Taylor Pyle received an invitation to accept an honorary Master of Arts degree in 1945. Aware that he would be overseas in June, Pyle wrote from U.S. Pacific Fleet headquarters in February:

"Dear President Conant: I am naturally deeply touched and appreciative of the honor....It is my regret that I cannot be there to accept it. Unless I get sick or something happens, I probably will be in the Pacific for a year or more. I understand that most universities have a policy of not awarding honorary degrees in absentia. If that is true of Harvard, then it is my deep loss.

But regardless, the basic good of the degree has been conveyed to me merely by your suggesting it....

Pyle was killed in action in April 1945, two months before Commencement. During the ceremony, President Conant broke tradition by announcing that Pyle had been voted an honorary degree. It is the only known instance in which word that a degree was voted but not conferred was officially made public.

|  |  |

| War correspondent Ernie Pyle was offered but never received an honorary degree. | Helen Keller, shown at her Radcliffe graduation, was Harvard's first woman honorand. | Oseola McCarty honored Harvard with her presence at Commencement in 1996. |

| Associated Press | The Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute | Jane Reed/Harvard News Office |

Harvard tradition was shattered again in 1955 when, according to newspaper accounts, 15,000 people rose to their feet and applauded Helen Adams Keller, A.B. 1904, the first woman ever to receive an honorary degree from Harvard. "A more moving event could not have happened to me," she wrote to the University, "than the generous sign of recognition from Harvard University of one who was once entombed in the silent dark...."When presenting her honorary degree at Commencement, President Nathan M. Pusey said, "From a still, dark world she has brought us light and sound; our lives are richer for her faith and her example."

In its subsequent account of the occasion, the Boston Daily Globe reported that many graduates had "thought that the first-woman honor would go to Dr. Helen Maude Cam, ...professor of history at Harvard and Radcliffe since 1945, but the Corporation ... chose to honor a woman whose name means more to the public at large."

In 1996, the praise was for Oseola McCarty, who donated her life's savings to the University of Southern Mississippi to aid needy black students. McCarty left school after the sixth grade and supported herself for 75 years as a laundress. In her eighties, she gave some money to her church, kept some to live on, and contributed the remaining $150,000 to the local university. In presenting her Doctor of Humane Letters degree, President Rudenstine called her "Selfless, steadfast, strong; a radiant reminder of Saint Paul's assurance that the Lord loves a cheerful giver."

Honorands are applauded not only for what they have achieved, but for what their presence contributes to the University. As historian Samuel Eliot Morison wrote, "An honorary degree is granted honoris causa, both to honor the grantee and the University."