When Julia Riew ’22 was growing up, everyone around her knew that she would write musicals. In elementary school, she turned recess into drama class, directing her friends in made-up plays like High School Moosical. After school, she sang in the St. Louis Children’s Choirs and played the guitar she took from her brother Grant ’19, M.B.A.’25, M.D.’26. In middle school study hall, she transformed her notebook paper into staff paper, composing violin duets that the school orchestra performed. I was her classmate back then, and I remember her strumming her ukulele backstage during the play we performed in together.

And yet, in college, Riew began to doubt the artistic future that seemed so clear to her friends and family. The summer before her first semester, she traveled to South Korea and met up with other incoming students of Korean heritage. It was an exciting trip because, although all four of her grandparents immigrated from Korea, Riew had had only one Korean friend growing up. But when she arrived on Harvard’s campus, she found that no Korean students were involved with theater. And women, she learned, were underrepresented backstage on Broadway. So she shifted her focus. All of the successful Asian American women she knew were doctors. At the end of her first semester, she switched her concentration from theater to the history of science and medicine.

Still, Riew did not let go of musical theater. She directed the first-year play and founded the Asian Student Arts Project, a student club that fosters an Asian art community. Each semester, she took two music and theater classes as “fillers.” Soon, the lines between art and science blurred. She wrote raps to memorize slides for pre-med exams, and in four of her history of science classes, she presented musical final projects.

Two sophomore year experiences helped Riew regain her confidence in musical theater. That spring, she wrote The East Side, a coming-of-age musical comedy that explored Asian identity and was performed by Asian actors. She invited students from Chinatown to the show. Watching their faces light up, Riew realized that “theater is not just something we do for fun,” she says. “The stories we are told…really shape how we see ourselves, how we see other people, and how we see the world.”

That summer, she did an internship with Korean-American novelist Min Jin Lee. “I had this terrifying fear of being weird,” Riew says. “I had this association in my mind that artist equals weird, that Asian artist equals weird.” But Lee told her, “I’m weird and I love it.” That gave Riew the license she needed.

Then came her “one-shot opportunity” to gain a professional foothold in musical theater. An American Repertory Theater (A.R.T.) producer watched Riew’s The East Side and then commissioned her to write two children’s shows: Jack and the Beanstalk: A Musical Adventure and Thumbelina: A Little Musical. In high school, she had played a leading role in Pippin and had spent hours studying videos of the Broadway version directed by A.R.T. artistic director Diane Paulus. At the A.R.T., Riew got to work alongside the prominent Asian American director (Paulus’s mother was Japanese), learning how to lead a cast and crew.

Riew’s senior thesis—a musical inspired by the traditional Korean folktale “Shimcheong” about a young woman who must journey across the sea to make it back home—launched her into the public eye. In 2022, she recorded herself singing the show’s titular song, “Dive,” in which the protagonist is about to make both a literal and metaphorical dive into her adventure. “There was no Korean Disney princess, so I decided to make my own,” wrote Riew on the video, which went viral. She snapped her fingers and her face transformed into a Disney-style animation. Riew’s cartoon face beamed as she belted an uplifting tune that one could imagine children singing one day. After graduation, Riew signed with an agent, secured a Harvardwood Artist Launch Fellowship, and won the Fred Ebb Award for aspiring musical theater songwriters.

Three years after graduating, Riew is working at a furious pace. She usually constructs two shows at once for regional theaters in the U.S. and South Korea—writing the book (script) for one while composing songs for the other. She is a rigorous outliner, laying out the entire plot before playing with a single note. She begins each show by determining its core message and its audience, writing both atop all of the show’s documents.

Often aimed at younger audiences, Riew’s musicals—much like her personality—are bright and uplifting. Each show has a specific mission. For example, ENDLESS (a mythological musical in development for a Korean premiere) shows that “although everything must end, sometimes, the briefest moments can stay with us forever,” she says. Riew’s works often encourage young people to explore stories, ranging from family tales to fictional narratives.

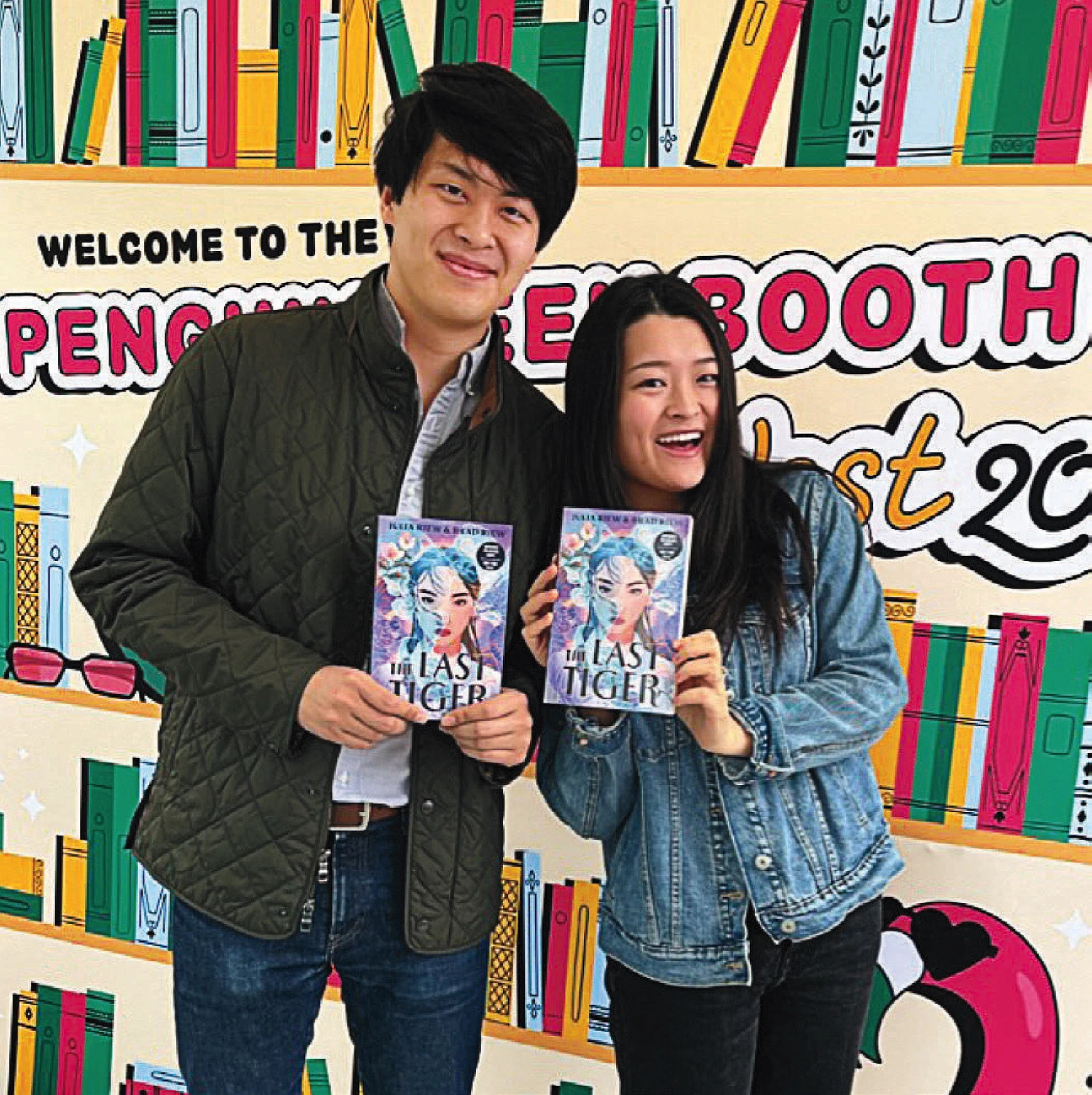

Riew loves the all-encompassing experience of watching a musical, but she is also experimenting with print. When Riew was young, her parents (Daniel ’80 and Mary, M.B.A. ’92) often brought her to a Borders bookstore, where she sprinted straight to the young adult fantasy section. Now, she has written a novel she would have loved as a child. The Last Tiger (Kokila, $21.99), published in July and co-written with her brother Brad ’18, is a story inspired by their paternal grandparents’ forbidden, secret romance in war-torn Korea.

The project began nine years ago with a high school English assignment to interview a family member. When she asked her grandfather to talk, he sent a 12-page account of the courtship between him and his wife and asked Riew to write a fictional version. After their grandfather died at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Riew siblings returned to that account and their grandmother’s stories to create The Last Tiger.

Riew has built a blossoming career around sharing Korean art. She traces her cultural interest to conversations with her grandparents about their upbringings. Though much of her work is centered around Korean folklore, she hopes that her art will inspire children from all backgrounds to investigate their own family histories. “It’s so moving to hear about where we came from,” she says. Perhaps those stories will come to life, too.