Drawing is rarely highlighted as a primary medium in the visual arts. Painting and sculpture often dominate the conversation—celebrated, elevated, canonized—while drawing is seen as mere preparation. But what of the humble pencil, charcoal, chalk, and crayon?

In many ways, drawing is the most direct form of visual expression. Unlike paint or marble, which impose demands and delays, the pencil allows the artist’s intent to move almost seamlessly from thought to paper without the need for additional tools or the mixing of media. Nothing except the limits of dexterity stands between idea and execution.

The exhibition Sketch, Shade, Smudge: Drawing from Gray to Black, on view at the Harvard Art Museums through January 18, 2026, offers a rare tribute to drawing as both a process and a product.

Rather than organizing the show by chronology, geography, or artistic movement, curators Miriam Stewart and Penley Knipe structured it around technique: the verbs of drawing itself. Stewart is the curator of the museums’ European and American art, while Knipe is a senior conservator who leads the Straus Center’s Paper Lab. The drawings are arranged according to artistic practice: “scrape,” “edge,” “lift,” “shade,” “refine,” “gesture,” and “smudge.” These categories guide viewers through the processes and decisions behind each work.

The effect is striking. Moving through the galleries, you can sense hundreds of hands in motion across time and space.

As the gallery texts explain, “shading” and “smudging” create depth and softness. “Lifting” uses erasers, cloths, or even bread to remove material and reintroduce highlights. “Scraping” also reveals the paper beneath, using sharp tools to emphasize or correct, sometimes leaving visible disruptions in the paper fibers. Artists “refine” their implements—sharpening graphite or chalk to achieve precise marks—or exploit natural wear to create expressive shapes. “Edge” is equally important, whether drawn with the side of a crayon or left blank as negative space. Finally, “gesture” refers to the physicality of mark-making—a swift stroke, a slow motion—and documents, according to the exhibit’s text, the “fine maneuvers of the hand or the greater gestures of the body.”

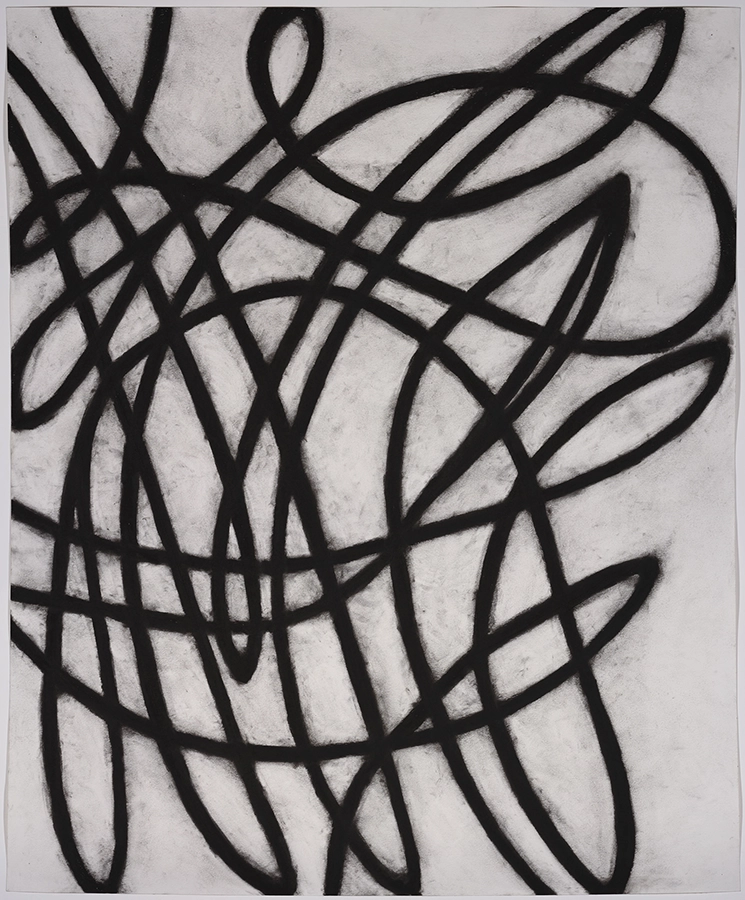

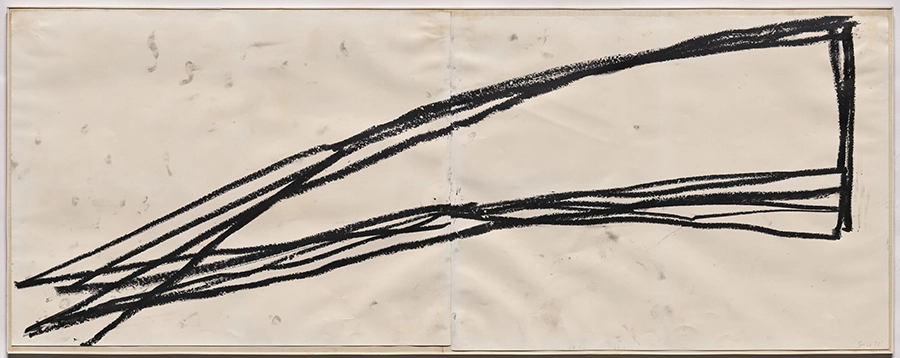

Gesture includes Amy Kaufman’s Tangle 2 (1999, charcoal on white wove paper), whose sweeping, twisting lines assert movement and confidence. Similarly, Richard Serra’s raw and emotional Study for One Plate (1972, paintstick on off-white wove paper) depicts a series of lines forming a geometric shape.

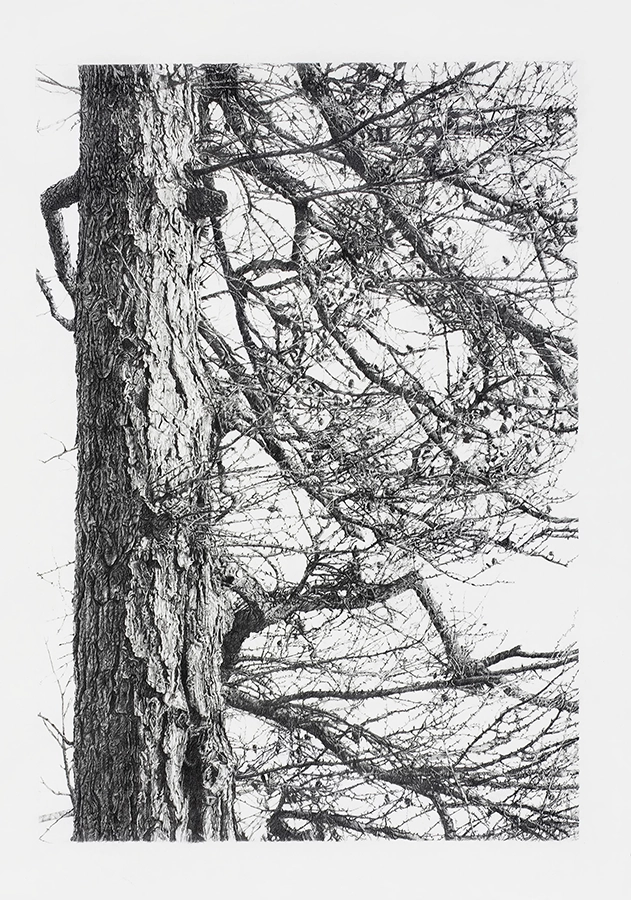

In contrast, a few walls away, works like Sandra Allen’s Auspice (2001, graphite on paper) are painstakingly rendered; the work is a near-photographic depiction of a tree with details of bark that reportedly took over 1,000 hours (nearly six months of work) to complete. Allen, based in Hingham, Massachusetts, takes pictures in the early morning and near dusk, when the light is at its best, and then works from blown-up gridded photos to make her drawings. Likewise, Spanish artist Isabel Quintanilla’s View of the Outskirts of Madrid (1969) is composed of unbelievably precise detail, including near-microscopic shading of small rocks in the field and distant trees smaller than a pinhead.

By placing these works in the same gallery and categorizing them based on the act of how they were created, the exhibit reveals drawing’s unique capacity to reflect registers of emotional intent. In a single room—painted a soft burgundy wine and offset by the grayscale of the drawings—the full expressive range of drawing as an act is shown.

A History of Drawing Materials at the Harvard Art Museums

A particularly compelling section of the exhibition focuses on drawing materials themselves—tools and paper. Dating to thirteenth century Europe, laid paper is made with a wire mould that leaves a visible grid pattern. Wove paper, developed around 1750, uses a fine woven screen that leaves little to no pattern. Both are still in use today.

Meanwhile, crayons, both wax and lithographic, became popular in the nineteenth century for their rich color and varied hardness. Charcoal, made from charred wood, produces soft, powdery marks. Long used in preparatory sketches because of its “smudgeability,” it gained artistic status as finished drawings became more popular in the nineteenth century. Graphite pencils, composed of pure carbon, offer a smooth, silvery mark that can be layered, erased, and refined. First used in sixteenth century underdrawings, graphite later evolved into a standalone medium celebrated for its versatility and subtlety.

There’s a political story behind that evolution. Until the nineteenth century, artists used natural graphite, often messy and imprecise. As the story goes, in 1794, amid the French Revolution and war with Britain, French engineer Nicolas-Jacques Conté developed a method of grinding inferior graphite, mixing it with clay, and baking it into consistent leads. This gave rise to the modern pencil. His “crayons Conté” (from craie, French for chalk), used in works throughout the galleries, became a staple that freed Continental artists from dependence on English graphite.

Meanwhile in America, Charles Franklin Dunbar, A.B. 1851—who held the first chair of political economy at Harvard—discovered a graphite deposit in New Hampshire and became business partners with his brother-in-law John Thoreau, A.B. 1837 (who would later change his name to Henry and write a certain book about his experiences living by Walden Pond). Before becoming the father of American transcendentalism, Henry David Thoreau improved the family factory’s pencil-making process. Their pencils, rated from No. 1 (softest) to No. 4 (hardest), were the finest made in the United States at the time. The Thoreaus’ numbering system is still in use today.

Beyond technical innovation, Sketch, Shade, Smudge also honors the democratic nature of drawing. Unlike oil paints or sculpting chisels, drawing materials are often affordable, portable, and immediate. A sketchbook can be kept in a coat pocket; a pencil can be borrowed from a stranger. Many of the works on display are excerpts from artists’ journals and reflect concepts that are intimate, offhand, or exploratory. For them, drawing is not just a formal act, but a habitual one, woven into daily life.

In this way, the exhibit is a kind of a “Drawing 101.” From start to finish, it walks visitors through artistic techniques, with examples easily at hand. Visitors are also invited to draw using provided materials, including pencils and papers. The curators stationed two sculptures—Georg Kolbe’s The Dancer (cast 1913–1919, bronze) and Auguste Rodin’s John the Baptist (1878–1881, bronze with black patina)—in the galleries for figure drawing practice, with cushioned chairs for sitting and observing.

In celebrating drawing as a verb, a practice, a material, and a thought, Sketch, Shade, Smudge makes a compelling case for its central place in art history. It reminds us that the nature of a single line on paper says something about a complex historical moment, and that black and white are anything but simple.