Addressing global crises—pandemics, financial collapses, climate change—requires global cooperation. But international institutions that were created to support geopolitical and economic stability, such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, may not be the best models for future forms of governance. Understanding the origins of these institutions, says assistant professor of history and of social studies Jamie Martin, could help policymakers perceive their shortcomings—and potentially point to better ways to tackle twenty-first-century problems.

The modern economic order, according to the prevailing historical narrative, was forged during World War II by the Allies at the 1944 Bretton Woods Conference. But Martin says the tools of modern international finance were not developed around a conference table in a few weeks; they emerged in response to specific crises over decades, stretching back to the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Knowing this history is key to understanding the foundation of global economic cooperation—and, Martin argues, its inherent imperialism.

In the late 1800s, an unprecedented amount of capital flowed from Europe and the United States to nations like Egypt, Venezuela, and China. Developing nations fell deeply in debt to their Western counterparts, and significant power imbalances emerged. During this first wave of globalization—a period of rapidly growing European and American imperial power—“some of the tools of lending that [were] developed” for “channeling European and American capital around the world…end up using tools of empire.”

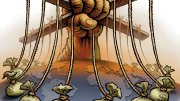

Western nations often attached onerous terms as a condition of their loans: if the debtor failed to make its payments, the creditor was entitled to extraordinary recompense. “Countries on the so-called peripheries of the world economy,” says Martin, would “lose control over sources of national wealth, natural resources, or the levers of policy.” Like colonies, “They end[ed] up having to sacrifice their sovereignty in exchange for financial assistance.” Lenders often forced compliance through military might.

At that time, powerful Western European nations generally avoided intervening in each other’s domestic affairs. But after World War I, the range of countries facing such interference changed. Defeated European nations now faced a degree of external interference that had previously been reserved for semi-sovereign countries such as Egypt or China. In his recent book, The Meddlers: Sovereignty, Empire, and the Birth of Global Economic Governance (Harvard University Press, 2022), Martin argues that powerful nations used conditionality to interfere in the national policy of weaker states.

The League of Nations, founded in 1920, helped mediate two types of conditional loans. In the early 1920s, its member nations lent large sums to governments in the former Ottoman and Habsburg territories to stop hyperinflation. Recipient states (including Austria, Hungary, and Bulgaria) had to accept a League-appointed financial adviser who would reshape the national economy to reflect the League’s ideal of liberal capitalism. Austria, which believed only “racially inferior” colonies should be subject to external control, nevertheless agreed to these humiliating terms in exchange for financial support. A few years after accepting the loan—having fired almost 100,000 government employees and committed to economic austerity to secure the funds—Austria’s currency stabilized and foreign investment capital once again flowed into the nation.

The League also served as the first international institution to oversee what are now called development loans. In the mid-1920s, for instance, the League of Nations’ Refugee Settlement Commission oversaw a major loan to Greece for resettling a million Greek Orthodox refugees from Turkey. The organization helped refugees by building houses, distributing livestock, and setting up small-scale manufacturing. It also attempted to collect debts from individuals. The League, Martin says, “pursued the entire settlement project and controlled the funds in a way that effectively made it unaccountable to the Greek government and beyond its control, which made it quite unpopular politically in Greece.”

Today, the two Bretton Woods institutions—the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank—perpetuate the legacy of these conditional loans, Martin contends. “When people tell the story of conditionality, they usually tell it as having arisen in full form in the aftermath of the Bretton Woods system,” he says. But that historical narrative ignores a century of conditional lending. “We have to see these twentieth-century contexts as deeply rooted in nineteenth-century arrangements.”

Modern global economic politics present these institutions with an opportunity to pursue reform. China is working to upend the Western financial system through its significant bilateral lending and its BRICS partnerships. As nations turn to China rather than Bretton Woods institutions to fund their bailouts and development, Martin says those organizations can reflect on their histories to find a path forward. Though the IMF and World Bank have approached contemporary problems with noble aims, their work often comes with significant concessionary controls.

Exposing the history of international financial governance, Martin argues that intruding on a state’s sovereignty may not be a necessary component of financial cooperation. By studying the past, he hopes to show that modern economic governance need not rely on imperially rooted tools. Instead, institutions like the IMF could make emergency liquidity available to member states without forcing them to sacrifice domestic economic control. “The countries that often need the financial assistance,” he says, “also tend to face the most difficult political obstacles to getting it.”

UPDATED October 17: An earlier version of this article listed Belgium, not Bulgaria, as accepting a League of Nations loan with harsh austerity terms.