Photographs and comment by Rosamond Wolff Purcell

|

| The densely striped Javan tiger, Panthera tigris sondaica, was common on that island in the early nineteenth century, but was hunted to extinction, perhaps by the 1980s. |

| Photograph by Rosamond Wolff Purcell |

|

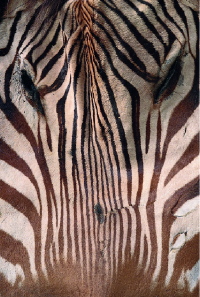

| The flattened face of a mountain zebra, Equus zebra. |

| Photograph by Rosamond Wolff Purcell |

I realize yet again how far the medium of still photography falls short of experience--how very far. No picture from this northlit room will ever capture the essence of the air, the thick clotted smells of dust, of hides, and grease-leaching bones. Whatever has been reduced by the scientist, is reduced in sensation one step further by the photograph.

The flatland of photography guarantees that the skulls--a dozen buffalo skulls from the flatlands of western America and a long-horned bull from Transylvania--will be translated out of their natural state, yet I know that details in the skulls may emerge on film as landscapes. I am often lost in landscape. I place the bones on the floor and inadvertently inhale their tainted fragrance--ah museum!