At his twentieth reunion, a classmate asked Peter Mee '76 what he'd been doing since graduation. "Oh, I've been researching brain injuries for the last several years," Mee told him. "It's interesting work." He neglected to mention that the research subject was himself. And the project, a lifelong endeavor, entails recovering from a stroke that stole about 70 percent of the left side of his brain.

It happened in 1982 when Mee, a strapping former star lineman for the Harvard football team, was in the middle of his surgical residency, with plans to specialize in orthopedics. One night he returned home after a long day, sat down in the kitchen, "and felt something weird in my head," he reports, "My right hand was getting rubbery. My eyes were funny. And I thought 'Something very bad is happening here.'" His family urged him to get some sleep, but, fearful, he called a neurosurgeon he knew who told him to get help immediately. En route to Mount Auburn Hospital in Cambridge, Mee collapsed in the car; his brother Gerry carried him into the emergency room. Within an hour of the attack, Mee was on the operating table under the care of doctors and nurses who knew him as Dr. Mee, with whom he'd worked side by side during a recent neurosurgical rotation.

|

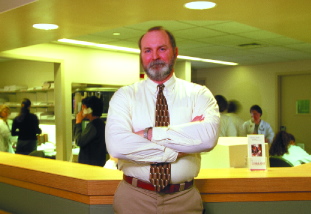

| After staging a remarkable recovery, Peter Mee now volunteers at St. Elizabeth's Medical Center in Boston. |

| Photograph by Stu Rosner |

Mere survival is not what Harvard alumni expect--as Peter Mee's quiet but stunning success in rehabilitating himself shows. "I call it an 'odyssey,'" says Rev. Carney Gavin, Ph.D. '73, a longtime friend of and pastor to the Mee family at St. Columbkille's Church in Brighton. "It's terrible and sad and frightening and filled with all kinds of encounters." Even in this age of dot-com billionaires, he adds, "There's nobody who doesn't question, 'What is heroism? What is worthwhile in life?' I cannot tell you how heroically Peter has worked to find a meaningful place for himself. It involved horrible, horrible failures and incredible obstacles."

Mee's stroke was caused by an arterial venous malformation--a congenital condition that can exist undetected for years--in the left hemisphere of his brain, says his neurologist, Dr. Thomas D. Sabin, professor and vice chairman of neurology at Tufts and a lecturer at Harvard Medical School and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. That section of the brain typically controls language and cognitive functions. The damage was likely compounded by post-surgical infections, adds Mee's sister, Patricia Marvin, a former nurse. "Within 48 hours he had a wound infection that made his whole brain swell," she explains. "Everything that could have gone wrong did."

The injury took a toll on his family life. He is no longer married, but has a close relationship with his son, also named Peter, who is now a sophomore at Boston College. Religious faith and family support have contributed greatly to his progress. "My whole family, from beginning to end, and growing up, have been Catholics, and I've always gone to Mass," he says. "That's 90 percent of how I've gotten through this. A lot of people in my position say they hate God, how could God do this? But this is not the time to walk away from God. You go to Mass and say 'Hey, I really need some help now.'"

Some medical experts who examined Mee along the way believed the cognitive functions were lost forever. "When I first saw him," says Sabin, "no other neurologists wanted to see him because the case was too depressing." Father Gavin describes Mee painstakingly copying the atlas from Gray's Anatomy, including beautifully rendered labels for the parts of the body. "He could see the lines of the letters, he could copy them," says Gavin. "But he had no idea what they were--that they were even letters and words." "It was like looking at Chinese if you don't know Chinese--what the heck is that thing there?" Mee recalls. "I could still draw, so that's what I tried to do to learn."

Since the stroke 18 years ago, Mee has been through three different rehabilitation hospitals and has also been cared for at home. From 1991 to 1998 he commuted to the Reading Disabilities Unit at Massachusetts General Hospital, where he finally recovered a limited ability to read and write. He now gets some news from the Boston Globe and, though it's slow going, looks at his old medical textbooks. Sabin says Mee "was born with language areas damaged on the left side of his brain. The right side was probably already working in that capacity" and Mee has since strengthened it. Mee's brain also had more plasticity than the typically older stroke victim, Sabin adds. "In his case, though, none of this would ever have worked without a lot of grit. He's a very strong-willed person," Sabin says. "He works hard. He practiced reading everything, even though he understood none of it, for hours and hours. He has really hoped to return to medicine. That has been a driving force for him."

At the moment, Mee is as close to being a doctor as he can get. With his formidable frame and Sean Connery beard, he looks the part as he volunteers three days a week at St. Elizabeth's Hospital in Brighton, around the corner from the home where he and his seven siblings grew up, and where he still lives with his mother, Mary, a retired Harvard secretary. His is a unique position at the hospital; his role--neither pastor, nor physician, nor full-time patient--is closest to that of peer counselor. Nurses guide him to patients who might want some company, and "my job is to make them feel good," says Mee. "There's nobody else whose job it is to do that."

He has enormous credibility with and empathy for patients--"You have to be in bed for a long time to know what it feels like. Patients are frightened," he says. He retains enough medical knowledge to know what's wrong, and inspires them with his own story. "Some people think they are going to die. People are down, their families are down. And I tell them that some people can get better--look at me. It's nice to give them a lift; to get them going again."

Ironically, he's a lot closer to patients than he would ever have been as a surgeon, but it remains painful to see medical-school classmates walking the floors teaching new students. "I say 'Hey, that guy's from my year.' Does that feeling kill you. But I look at football as an example. Look at the half. If you're losing at the half, do you walk home? No. You keep going. That's the feeling that keeps me going. Underneath it all, I still have goals."