All of David McCullough's previous subjects were born in the nineteenth or the twentieth centuries, so this book on John Adams marks a departure for him. Here some personal disclosure is called for. McCullough resides year-round in the small town where I live in the summers (West Tisbury, Massachusetts), and we know each other through that and other connections. In the acknowledgments, he thanks me (along with a host of other people) for my "encouragement" of this project. That encouragement consisted (as best I can recall) of a conversation that occurred in West Tisbury shortly after he had decided to write what he expected to be a joint study of John Adams and of Thomas Jefferson, focusing on their 50-year relationship that began with political alliance, continued through friendship and political enmity, then ended with friendship again (although a strictly epistolary one) in the last years of their lives. Since I have spent years studying the eighteenth century, and he--at that time--found the colonial American period very alien, he asked me somewhat anxiously if I thought that John Adams would "stand up to" Jefferson. "Oh, yes, David," I recall myself reassuring him, "that will not be a problem." These many years later, John--and Abigail--have taken over the book, and Jefferson appears more in its interstices than at its center. It was Jefferson, then, who did not stand up to Adams, although among Americans today he is probably the more celebrated of the two men, because of his authorship of the Declaration of Independence and his longer and more successful presidency.

Adams took over the book for multiple reasons, some of them undoubtedly having to do with the simple availability of sources. For one thing, as a young man John Adams kept a remarkably revealing diary, on which McCullough regularly draws. Jefferson kept detailed account books throughout his life, but never a diary. For another, John had Abigail with whom to exchange possibly the most remarkable set of intimate letters in American history. Jefferson was a widower for much of his adult life, and after his wife's death in 1782 he burned their letters, as he had previously burned his mother's papers. Jefferson frequently wrote to his daughters, but in a didactic mode that did not lend itself to personal reflection and revelation. At the most basic level of all, John and Abigail Adams were separated for months or years at a time during crucial periods (most notably, from 1778 to 1784), and so they had to write letters to each other in order to communicate--letters that were then saved by their descendants. Such contingencies, although non-historians rarely consider them, often determine much about how the past is remembered and written of.

But the nature of the sources, too, is important. John Adams did not--did not want to--conceal his true self in his writings. In many ways, he wore his heart on his sleeve, and his words and thoughts flowed freely out through his ever-active pen. With Adams, it was truly WYSIWYG (what you see is what you get). Adams was, in modern parlance, an up-front guy. Sometimes that characteristic helped him, sometimes (perhaps more often) it hurt. But his openness is a boon to anyone who wishes to write about him. By contrast, Jefferson, who also wrote voluminous letters, was far less personally revealing and at many levels turns out to be unknowable; not surprisingly, one of his most recent biographers, Joseph Ellis, titled his book about Jefferson American Sphinx. One could not imagine John Adams, for instance, having maintained utter silence about a long personal relationship, even one as complex and forbidden as was Jefferson's with Sally Hemings. So John--and his equally candid wife, Abigail, also a prolific writer of letters, not only to John but also to her two sisters and her children--have regularly seduced biographers. We can now add David McCullough to that happy list.

Son of a Braintree farmer and his higher-status wife, educated at Harvard (class of 1755), John Adams first taught school and then read law. By the early 1770s, he had developed into one of Massachusetts's most effective attorneys and had a large law practice. As a staunch patriot, he participated actively in the revolutionary movement, served in the Continental Congress, and was dispatched to Europe as one of the new nation's first diplomats. Based in France and then in the Netherlands during the war, he negotiated a large loan from Dutch bankers that helped to keep the United States afloat financially during the latter stages of the Revolution--an achievement he always (and quite rightly) regarded as one of his most important. The first American ambassador to Great Britain, he returned to this country after the adoption of the Constitution and was elected the nation's first vice president. After faithfully serving in the Washington administration for eight years, he was himself elected president in 1797. Unfortunately, however, it was to be a one-term presidency, as an undeclared naval war with France abroad and partisan politics at home made life difficult for him. Replaced in office in 1801 by his one-time friend and now bitter rival Jefferson, he retired to Braintree, where he watched from afar as his political allies, the Federalists, were routed by Jefferson's Republicans over the next few years. In 1812, he and Jefferson took up their pens and thereafter, agreeing to let bygones be bygones, together created for posterity (as they well knew they were doing) an unprecedented set of recollections of the Revolution and a continuing dialogue on political topics. When they both died on July 4, 1826, the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, the citizens of the United States understood that an era had ended.

|

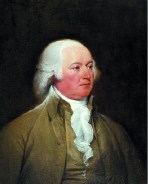

| Painting by Mather Brown, 1785 The Boston Athenaeum |

If McCullough's intense focus on his subject, then, sometimes leads to a neglect of broader contexts, it has the concomitant advantage of sharpening the reader's view of John Adams the man. McCullough is especially adept at showing the human side of his subjects--not just John, but also Abigail and their children, especially their oldest child, Abigail Jr. (Nabby), and John Quincy. John Adams the lifelong farmer and lover of his New England home, Abigail the provincial woman dazzled by London and Paris, Nabby the dutiful daughter and frequently deserted wife, John Quincy the stalwart young diplomat: all emerge from this book as fully developed individuals demonstrating deep love and genuine respect for each other.

The most important decision the young John Adams made, McCullough believes (and many others would agree), was to marry the intelligent, spirited Abigail Smith, the short, frail daughter of the minister of Weymouth. "She saw what latent abilities and strengths were in her ardent suitor and was deeply in love. Where others might see a stout, bluff little man, she saw a giant of great heart, and so it was ever to be," McCullough comments. Their relationship endured repeated separations, the tragic deaths of babies and adult children alike, the many vicissitudes of late eighteenth-century politics. Abigail always addressed John as "my dearest friend," was consistently his fiercest defender, and when she died in 1818 he wrote resignedly to John Quincy that "my consolations are more than I can number. The separation cannot be so long as twenty separations heretofore."

|

| Painting by John Trumbull, 1793 |

|

| Painting by Gilbert Stuart, 1826 |

Mary Beth Norton, Ph.D. '69, is Alger professor of American history at Cornell University. The author of two books about the American Revolution and one about seventeenth-century English America, she is currently finishing another, on the Salem witchcraft crisis of 1692.

John Adams, by David McCullough (Simon and Schuster, $35).