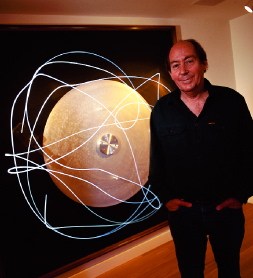

Spend a day in church with Paul Matisse '54 and you will marvel at how the creator has shaped his world. Everywhere you look you see a sculpture, an ingenious device, a handsome space or object that Matisse has made or designed for his home of the past 20 years, on Main Street in Groton, Massachusetts, 50 minutes by car north of Cambridgehis home in a former Baptist church.

When you enter the ground-level door of Matisse's dwelling, you find yourself between two staircases that lead up to the former sanctuary, which he calls the large studio in an attempt to desanctify the terminology of the place. If you ignore the stairs, you can walk straight through the next set of doors into the machine shop, and, beyond, the woodworking shop, the lab, a secretary's office, and the agreeably cluttered office of the artist and inventor. The industrial areas are crammed with serious tools used by Matisse and two assistants. The first thing to confront you as you enter the machine shop is an object made therea long, thick aluminum tube, suspended horizontally about five feet from the concrete floor. In two places along its length, metal has been cut away in concave parings to tune the tube, for it is a bell, of Matisse's invention. When struck, the astonishing instrument emits a low, solemn tone that pulsates, stronger and weaker, like breathing.

Matisse's most recent commission was to make the Memorial Bell for the National Japanese-American Memorial to Patriotism, which opened last July in a triangular park of something less than an acre at Louisiana and New Jersey Avenues and D Street, N.W., in Washington, D.C., within sight of the Capitol. The memorial is first an apology to the 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry, many of them U.S. citizens, who were forced from their homes by Executive Order 9066 during World War II and put into 10 internment camps in seven states, where most stayed for more than three years. It is as well a tribute to the Japanese Americans who served in the U.S. military during the war, more than 800 of whom gave their lives.

The floor plan of the park within its triangle is a loop design, symbolizing regeneration, and is the work of architect Davis Buckley. One enters and moves straight to the center, where semicircular granite walls more than seven feet high flank a 14-foot-tall bronze sculpture by Nina Akamu of two cranes ensnared in barbed wire. On one wall are inscribed the names of the camps. Through a notch in the other, one sees a serene pool of water. Then one continues around the spiral to the end of the memorial, Matisse's bell.

Eighteen feet long, eight inches in diameter, the hollow tube is cradled in two bronze arms against curving granite slabs. Any visitor may sound it by pushing on a waist-high bronze lever that activates the hammerof stainless steel, bronze, and cast urethaneabove the bell. Matisse took three years to perfect the tone of the bell, so many variables had to be considered. When he had the finished bell in his quiet shop and struck it, its deep voice was audible for eight minutes, slowly fading in a long decline he describes as "the natural way of things, a falling away of grief."

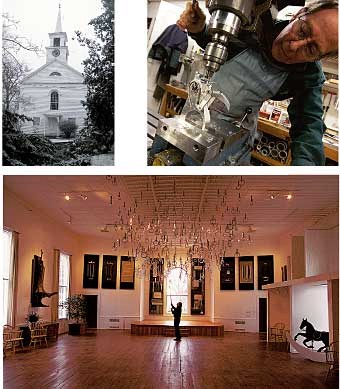

Business gets done at the bottom of the church. The large studio, one floor up, serves as a fine, open placeflooded with light and refreshing to walk through from time to time during the day; as a gallery now displaying on its walls collages by Matisse's second wife, Linda Hoffman; and as a venue for occasional chamber-music concerts (to benefit the Indian Hill School of Music of Littleton, Massachusetts).

Suspended from the studio ceiling is a cloudlike, 400-element sculpture called Ulysses, begun in 1983 for General Electric but never finished because the company abandoned, for budgetary reasons, the program with which it was to be associated. As conceived by Matisse, the cloud "would be controlled by a computer, one whose first task every morning would be to create the script for the day. Each element could be raised or lowered to occupy an exact position in the matrix. Each element incorporated a light that could glow at 16 levels of intensity and a tuned musical ring that could be struck at an exact time and with a determined force. Many chance and nonchance elements would determine the choreography of the parts, the play of the lights, and the musical use of the rings. The rings were to be tuned in quarter tones to ring from the C-sharp above middle C up to the next C-sharp, 25 tones in all."

|

|

| The Memorial Bell at the National Japanese-American Memorial in Washington, D.C. |

| Maxwell Mackenzie (top) and Davis Buckley Associates (bottom) |

Spin the Kalliroscope, and the flows of the currents within are strikingly apparent. They seem mighty in their pace and vast in scale, like those of a sea. Or touch a still, shimmering surface with your warm fingertips or with a cube of ice and the fluid comes alive with motion. Once energized by any means, the fluid's objective, slowly and complexly realized, is to come to rest, to placidity. Here is conflict in the process of resolution. What you see, Matisse would say, is an analogue of life.

Matisse once manufactured Kalliroscopes commercially in various shapes, sizes, and fluid colors. Now, he will create a big one when a museum wants it, and he makes the fluids in his lab downstairs for sale to scientific researchers and teachers worldwide.

|

| The Second Wheel has two pendulums of aluminum and brass, each containing a small light, that can rotate freely on axles attached at opposite sides of the aluminum disk. "I start the wheel," says Matisse, "by giving it three or four vigorous turns, by hand. Then I stand back, usually amazed at the violence of the forces delivered by the wildly asynchronous pendulums. They shake the wall that the wheel is mounted to with such force that soon the entire frame of the church is trembling. When the spin exhausts itself and the wheel starts to slow down, I watch the pendulums seeking out their synchronicity. As their energy level falls, they become more and more attracted to swinging in perfectly parallel motion, but they have to go through a long period when one or the other will be going too fast and somehow forcing its opposite twin to go too slow. I watch them trade places back and forth, knowing that they will never lose track of their goal of moving together. As they transition from the chaos of their first explosive moves and drift down into the calm authority of their long-sought harmony, I never fail to hope that we will all someday be able to do the same." |

| Portrait by Jim Harrison |

The dining room contains works by Linda Hoffman along both long walls, and at each end a disk-shaped metal scupture by Matisse (see one above). The 12-foot-long walnut and ash table of his design has soapstone warming panels for platters at its center and drawers for storage, and it is big enough to accommodate his large family when assembled. With his first wife, Sarah Barrett, Matisse had four children (one of whom, Sophie, is a painter who has just had her first solo gallery show in Manhattan), and he had three children with his second wife. Matisse and she are living apart now, but daughter Ariel, age 12, remains in residence.

The living room houses memories of past lives. Matisse is the grandson of painter Henri Matisse. His father, Pierre, founded one of the first modern art galleries in the United States. His stepfather was painter (and chess player) Marcel Duchamp. In one corner is a fine old Morris chair that was the only chair in Duchamp's last studio. Over there is a marvelous chess set made by painter Max Ernst around 1948. (Matisse has just spent what he calls "two intense nights" with Ariel working on a Viking chess set, "in the making of which she insisted on calling all the shots.")

The mantelpiece and adjacent cupboards in the living room are of Matisse's design, and he thought and thought about how to devise a single knob for each cupboard that would open both of its doors simultaneously. The result: on the outside, a simple, short, vertical piece of metal where the doors meet; on the inside, more-complicated hardware; all made of brass in the shop downstairs.

The next floor up contains rooms for the children. The stairway has a railing of unusual design, and its curved cap, or wreath, as it changes direction, rising, is one of the more difficult things to make in home carpentry, but Matisse, temporary handrailer, figured out its mysteries and fashioned it, of mahogany.

The master bedroomof Japanese aspect, made of cedar, limestone, and brass is the fourth floor's main event. Its adjoining bathroom contains a capacious, consequential tub. Matisse wanted it to have no faucets and figured out how to plumb the tub so that it both filled and drained from an inlet/outlet at the base.

Mount a rustic stair to the fifth floor, and you may admire amidst old beams the Howard tower clock that Matisse keeps running accurately to mark the hours for Groton. The bell is up a ladder on the sixth floor. A weathervane tops off the steeple at 90 feet above terra firma. The original church structure was completed in 1842. The bell went into the belfry in 1875, when a bell could be afforded, and the clock came along in 1893, in the fullness of time.

You have lunch in the kitchen at a table made of jack pine from the former baptismal bath. Lentil soup, salad, crusty bread, cheeses, including mimolette, a chewy, pumpkin-colored, spherical, French variety. Matisse discourses on the physics of a vinaigrette and what's happening when a mayonnaise breaks. He attended Harvard, he tells, because he thought the professors would teach about life. When he found that that wasn't on offer, he concentrated in Romance languages, a field whose relatively few requirements permitted him forays into math, physics, psychology, social relations, Russian literature, music, even art.

He became part of Harvard legend. In the fall of 1951, he was rooming in Eliot House A-12 with Stephen Joyce and Sadruddin Aga Khan. As Matisse remembers it, Master John Finley bragged about the House to a New York Times reporter, as in "Where else would you find, in one room, the grandson of Matisse, the grandson of Joyce, and the great-great-great-great-grandson of God?" The story got into the paper, and into Harvard history, and Matisse dimly remembers an embarrassed apology from Finley afterwards.

|

| Clockwise from top left: Matisse's home sweet home. At work in the machine shop. The large studio, with the 400-element sculpture Ulysses. (Matisse adjusts a spotlight.) |

| Photographs by Jim Harrison |

Matisse went on to study at the Graduate School of Design, but did not take a degree. He noodled around in new-product development at Arthur D. Little Inc., in Cambridge, from 1958 through 1962, and then he set off mostly on his own with Kalliroscopes.

The process of making is a daily joy for Matisse. But the core of his life has always been, he says, the search for illumination. "I live for the meaning that I need to see in the world, for the complex but perfect relationships between parts that carry the beauty, and when I find a few rays of that kind of light, I reradiate it in a form made possible by my gifts, which are no more elevated than being fairly good at making things that work."

For Alexander Calder, from 1977 through '79, working from Calder's 22-inch model, Matisse engineered, constructed, and installed the 28-times-larger mobile that hangs in the east wing of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. In 1980 he completed The Musical Fence, two interactive sculptures commissioned by the City of Cambridge, the first of several commissions he has had for interactive musical sculpture. (The Fence became a public nuisance because passersby played it in the small hours, sometimes with hammers and rocks, and eventually Matisse sent the two parts to different museums.) From 1986 through 1988, he designed, fabricated, and installed in the Kendall Square subway station in Cambridge The Kendall Band, a three-part musical sculpture, consisting of "Kepler," a 55-inch ring; "Galileo," a sheet of stainless steel that imitates a train roaring in when a train roars in; and "Pythagoras," twin sets of eight bells of the type of the new memorial bell in Washington, but hung vertically. These are squeezed into the narrow space between incoming and outgoing tracks. Handles on each platform allow people waiting for trains to activate hammers that strike the bells.

"Pythagoras" broke several times in the beginning when overzealous subwayites jerked the handles too forcefully. Matisse posted signs to let people know the progress of repairs. The signs were quickly covered with grafittimost, but not all, expressions of appreciation ("Radical move, dude") or erudite constructive criticism from MIT students. Matisse was delighted to have stimulated dialogue. One commentator wrote: "If you spent any tax dollars on this, may you die slowly." Just underneath that sentiment, in much finer handwriting, another traveler countered: "... may you live long and happily."

~Christopher Reed