"Was introduced to Miss Kate Loring, a most charming and lovely girl....I danced with her twice or three times, and found her very pleasant and well-informed, and very lady-like. I thought of her all night instead of going to sleep. If there ever was a fool, his name is Frank Abbot."

On January 17, 1857, nine days later: "Katie is apparently seventeen or eighteen, small and slightly made, and to me very beautiful; rather pale, with hazel eyes and that peculiar kind of light hair, that you do not know whether to call it light or dark....She is certainly a sweet and lovely girl, but I am not in love with her yet."

On January 17, 1857, nine days later: "Katie is apparently seventeen or eighteen, small and slightly made, and to me very beautiful; rather pale, with hazel eyes and that peculiar kind of light hair, that you do not know whether to call it light or dark....She is certainly a sweet and lovely girl, but I am not in love with her yet."

On January 25, Francis Ellingwood Abbot, A.B. 1859, then a sophomore, kissed Katharine Fearing Loring, of Concord, Massachusetts, for the first time. Then he put his head in her lap. "'O God! I thank thee! O God, I thank thee!' was all I could gasp out," he wrote in his journal.

Abbot's journal is one of about 200 student diaries and scrapbooks of the nineteenth century in the Harvard University Archives. Reference archivist Brian Sullivan is transcribing Abbot's as time permits, for it is both a document full of rich detail about hazing, College food, and the oddities of the professoriate, and a cracking good Victorian melodrama.

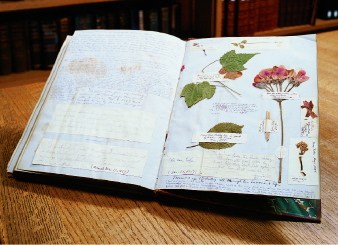

On the day he kissed Kate, Frank asked her father for her hand. "'This is rather sudden, Mr. Abbot,' he replied," Abbot recorded in his journal. They were too young, said Mr. Loring, to form an engagement, but could continue courting. Later that day, Frank passed Kate a note: "We can hope." Pasted into the back of the journal many years later is the very note (see below), with the annotation by Abbot: "Treasured up by my darling all through her innocent life." He himself had treasured up significant flowers and leaves, as well as a coil of Kate's hair, given him three days before that first kiss.

They were married after Commencement in 1859 and went to Pennsylvania, where Frank got a degree in divinity. He occupied Unitarian pulpits for five years, but split with the church and helped organize the radical Free Religious Association. He was briefly an instructor in philosophy at Harvard, but chiefly taught in a private school for boys in Cambridge and wrote works on philosophy and religion. The Abbots had two sons, Everett V. '86, LL.B. '89, and E. Stanley '87, M.D. '93, and a daughter, Fanny. In 1893, Kate died. Frank was devastated.

|

| Abbot: Harvard University Archives; |

Just after he met her, Abbot told his journal: "...when I am an old man (if I ever am one) these pages may bring back the days of my youth, when every feeling partakes of the nature of excess...." After her death he noted in the margin, "Now I am oldand just the same! My love is just as impetuous, as overpowering, as passionateall the more because now its name is grief."

On the tenth anniversary of Kate's death, Frank took a bunch of carnations to her grave, drank poison, and died.